Cellulosic ethanol production could fight Gulf Dead Zone, help fisheries

Cellulosic ethanol production could fight Gulf Dead Zone, help fisheries

Rhett A. Butler, mongabay.com

January 16, 2008

|

|

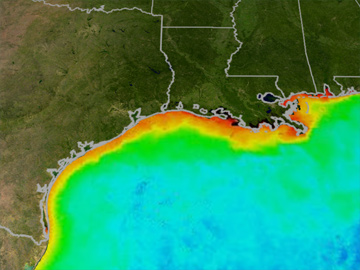

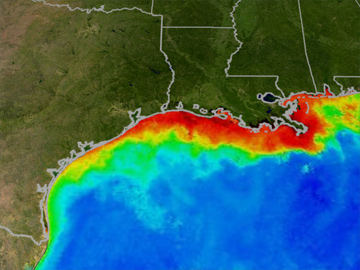

Feedstocks for cellulosic ethanol production could help fight the massive “dead zone” that forms each year in the Gulf of Mexico as a result of current farming practices, says a University of Alabama in Huntsville biologist.

The hypoxic or dead zone, an expanse of water so devoid of oxygen that sea life cannot live in it, partly results from the use of nitrogen-based fertilizers for corn crop. With corn acreage rapidly expanding in the U.S. under subsidies for ethanol production, more fertilizers are ending up in the Gulf: each year an estimated 210 million pounds of excess nitrates are carried to the Gulf promoting massive algae blooms that fuel the hypoxia.

Dr. Gopi Podila of UA Huntsville says that a shift toward cellulosic ethanol — which uses farm waste, weedy grasses, and fast-growing trees as feedstocks — could reduce the need for fertilizers while offering higher yields for biofuel production.

|

“Ethanol from cellulose, whether from trees or other sources, will be the way to go in the very near future,” he said. “Trees are cheaper to raise than corn, have a competitive yield and they don’t need as much of the fertilizers that are causing all of the problems in the Gulf. These trees also offer the U.S. a realistic option for producing enough renewable energy to make a meaningful dent in fossil fuel imports.”

Podila says that fast-growing trees for cellulosic ethanol production may also be cheaper than corn and could grow on marginal lands.

“For one thing, there are some trees like poplar and aspen, where you could get a harvest every five or six years but you would only have to plant once every 30 to 40 years because they grow back from the roots. That is a significant cost savings, if only for the fuel used for planting and harvesting every year,” he said.

“Many of these trees and grasses like switchgrass will grow on land that might have marginal value for farming. Maybe it is too steep for planting or too dry for farming, but that wouldn’t be as much of a problem for trees. You could have an extra crop growing on land that isn’t presently productive. There are vast areas of marginal land in the U.S. that could be used for this purpose without having an impact on other crops.”

While some environmentalists are concerned about invasive energy feedstock species, Podila says that some native species are good candidates for cellulosic ethanol production, including southern poplar and sweet gum in the southeastern United States.