Amazon deforestation surging due to oil, soy prices

Amazon deforestation surging due to oil, soy prices

mongabay.com

January 17, 2008

|

|

A Brazilian scientist has confirmed that forest clearing in the Amazon rainforest has surged in recent months, according to Reuters.

Carlos Nobre, a scientist with Brazil’s National Institute for Space Research, which tracks Amazon deforestation, told a seminar in Washington that deforestation “is going to be much higher than 2007.”

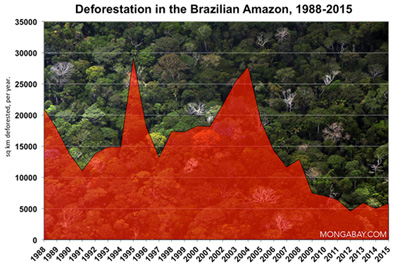

Nobre said that 2,300 square miles of forest had been cleared in the past four months, compared with 3,700 square miles in the 12 months ended this past July 31. The Brazilian government had championed the 2006-2007 numbers — the lowest annual forest loss since the 1970s — as a sign that enforcement efforts were working in the region, but scientists said the decline was more likely a temporary one tied to slowing global commodity prices. As soy and cattle prices have risen in recent months, the number of fires and apparent forest clearing have also increased.

|

Brazilian satellite data show a marked increase in the number of fires and deforestation in the region. The states of Para and Mato Grosso — the heart of Brazil’s booming agricultural frontier — both experienced a 50 percent or more increase in forest loss over the same period last year coupled with a large jump in burning: a 39-85 percent jump in the number of fires in Para during the July-September burning period and 100-127 percent rise in Mato Grosso, depending on the satellite. More broadly, the 50,729 fires recorded by the Terra satellite and 72,329 measured by the AQUA satellite across the Brazilian Amazon are the highest on record based on available data going back to 2003 (the NMODIS-01D satellite suggests 2005 burning was higher but still shows a 54 percent jump since last year). Reports from the ground indicated that burning was indeed very last fall.

“I have never seen fires this bad,” John Cain Carter, a rancher who runs the NGO Aliança da Terra, told mongabay.com. “The fires are even worse than in 1998´s El Niño event… A huge area of the Xingu National Park was on fire, truly sickening as it is a sign of things to come.”

Satellite imagery from NASA indicates that much of the burning late last year was concentrated around two major Amazon roads: Trans-Amazon highway in the state of Amazonas, and the unpaved portion of the BR-163 Highway in the state of Pará. Scientists have long warned that the roads would drive deforestation in the area by encouraging settlement and development.

“Infrastructure is associated with aggressive and progressive land use change,” said Nobre, noting that 90 percent of Amazon deforestation occurred within 30 miles of roads, according to Reuters.

Nobre also said that high oil prices would create further pressure on the Amazon for biofuel production.

“If oil prices keep increasing there will be an explosion of biofuel production in the Amazon,” he said.

Nobre’s comments come shortly after Brazilian Agriculture Minister Reinhold Stephanes told Reuters that Brazil would need at least a decade before it could stop deforestation resulting from its fast-growing agriculture business.

“Today Brazil has the conscience not to cut down trees to increase its production,” he was quoted as saying. “The government has decided — no more deforestation. Now, it will be at least a decade before the policies are in place and working.”

Stephanes told Reuters that Brazilian agriculture would grow by recovering 50 million hectares (124 million acres) of degraded pasture land as well as converting 50 million hectares of cerrado, a grassland ecosystem bordering the Amazon rainforest. Critics say that landowners often bribe officials to classify forest land as cerrado so they can clear it for pasture and soy farms.