Conservation promotes larger fish stocks and higher profits for fishermen

Conservation promotes larger fish stocks and higher profits for fishermen

mongabay.com

December 6, 2007

Using conservation techniques can promote larger fish stocks and higher profits for fishermen, reports a study published in the journal Science. The research suggests that industry opposition to lower catches in the short term, may be misguided.

Australian National University economist R. Quentin Grafton and colleagues examined catches of four species — big eye tuna and yellow fin tuna of the western and central Pacific, northern tiger prawn and orange roughy in Australia — in the waters around Australia and showed that fishermen can maximize profits by catching fewer fish and leaving more in the ocean to replenish depleted stocks.

“It has always been assumed that maximizing fishing profits will lead to stock depletion and possibly even extinction of some commercial species,” said study co-author Quentin Grafton, research director at the Crawford School of Economics and Government at the Australian National University (ANU). “But our results prove that the highest profits are made when fish numbers are allowed to rise beyond levels traditionally considered optimal. In other words, bigger stocks mean bigger bucks.”

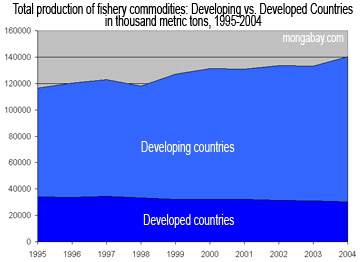

Total production of fishery commodities from 1995-2004: developing versus developed countries |

The authors say that when fish are more plentiful and therefore easier to catch, fishermen spend less on fuel and other costs. This results in higher profits.

As such research suggests that laws based on fishing at the “maximum sustainable biomass level” do not yield the best results for fishermen or fish stocks. Instead, the authors say, “fishing at the level of maximum economic yield minimally affects the amount of fish for sale and also cuts costs, allowing fishers to make more money and to maintain sustainable levels of fish,” according to a statement from Science.

“Conservation promotes both larger fish stocks and higher profits,” explained Tom Kompas, an economist at Australian National University’s Crawford School of Economics and Government. “This is a win-win for the world’s fisheries and for the global marine environment. The debate is no longer whether it is economically advantageous to reduce current harvests — it is — but how fast stocks should be rebuilt.”

The U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) estimates that 25 percent of world fish stocks presently depleted. The research shows that rebuilding fish stocks is in the best ecnomic interests of the fishing industry.

|

“We found that the more overexploited the fishery, the greater the profit benefits of stock rebuilding,” said study co-author Ray Hilborn, a professor of aquatic and fishery sciences at the University of Washington. “Although the stock effect may be relatively small in some cases, our estimates indicate that it is large at current stock levels while harvesting costs rise at an increasing rate as stocks decline.”

“We believe these results will help persuade fishers that it is in their interests to take the long-term view — that by reducing their catch now they will more than make up any temporary financial losses with increased profits in the future,” said Grafton. “This is quite a different argument from the current focus on sustainability. In this framework, we can say, ‘What you are doing now is costing you money but if you reduce the harvest now, it will pay off down the road.’ I think that in a lot of cases, that could be seen as an attractive proposition.”

“Fishers around the world have heard a lot of arguments for rebuilding stocks,” concluded Hilborn, “but I think that we are sure to get better buy-in when we can show them that today’s pain leads to tomorrow’s gain so long as fishers have long-term harvesting rights such that they can personally benefit from increased fish stocks.”

Related articles

How to save the world’s oceans from overfishing

Global fishing stocks are in trouble. After expanding from 18 millions tons in 1950 to around 94 million tons in 2000, annual world fish catch has leveled off and may even be declining. Scientists estimate that the number of large predatory fish in the oceans has fallen by 90 percent since the 1950s, while about one-quarter of the world’s fisheries are overexploited, depleted, or recovering from depletion. Unsustainable fishing practices like bottom-trawling and some forms of long-lining not only deplete targeted species, but net sea birds, turtles, and other marine life, while destroying delicate ecosystems like deep-sea reefs. About one quarter of global fish catch is tossed back overboard, dead or dying, as bycatch. At the forefront efforts to slow marine degradation is Mike Sutton, director of the Monterey Bay Aquarium’s conservation program: the Center for the Future of the Oceans. The aquarium, which has long been recognized as one of the world’s most important marine research facilities, is pioneering new strategies for protecting the planet’s oceans.

CITATION: R.Q. Grafton, T. Kompas, R.W. Hilborn (2007). “Economics of Overexploitation Revisited” Science, December 7, 2007