The State of Forests and Ecotourism in Belize

The State of Forests and Ecotourism in Belize

An interview with Colin Young, a Belizean Ecologist

mongabay.com

November 16, 2007

A 7-year old nature guide grows up to become environmental and scientific role model for Belize

Each year hundreds of thousands of nature-oriented tourists visit Belize to see the Central American country’s spectacular coral reefs, biodiverse rainforests, and ancient Mayan ruins. However few visitors realize that Belize’s natural resources are at risk. Timber and oil extraction, agricultural encroachment, coastal development, pollution and unrestrained tourism are all increasing threats to Belizean ecosystems. Unless something is done to address these concerns, within a generation these pressures could present considerable problems for Belize.

Colin with Costus pulverulentus in the rainforest of Belize |

Dr. Colin Young, head of the environmental science program at Galen University in Belize, says that while he is greatly concerned about these issues, there is still time to ensure healthy forests and reefs in Belize. Young, a native Belizean who, at age seven, started working in as a tour guide in the Community Baboon Sanctuary, says that community management of forests, responsibly planned ecotourism, and greater emphasis on local science education could go a long way towards smarter and more sustainable use of Belize’s natural resources.

In a November 2007 interview with mongabay.com, Young discussed the threats to the Belizean environment, his outlook for its forests, measures for getting more local children to pursue careers in science, indigenous use of medicinal plants, and lessons learned from conservation efforts in the country.

INTERVIEW WITH DR. COLIN YOUNG

Mongabay: What is the focus of your research?

Young: My current research is very interdisciplinary and spans a number of areas including the distribution and diversity patterns of useful species across landscapes, Belizean Creole Ethnobotany, reliability of ethnobotanical knowledge, community-based conservation initiatives and policy development and its impact on conservation.

Mongabay: How has your background influenced your current work?

Colin in Belize. Photo by Bruce Holst of the Marie Selby Botanical Gardens. |

Young: In 1981, at only seven years old, I became a tour guide at the Community Baboon Sanctuary (CBS) — a 20 square mile sanctuary dedicated to protecting the endangered Black Howler Monkey, Aloutta pigra, locally called “baboons.” My father was the first manager and local founder of the sanctuary, thus I had ample opportunity to learn about the natural history of the monkeys and other fauna and flora of the CBS. This early exposure to natural history sparked my interest in ecology. The CBS was one of the first experiments in community-based conservation in Belize. It relied on the voluntary participation by members to abide by certain land management techniques that would allow them and the monkeys to co-exist. Currently, the sanctuary is home to over 6,000 monkeys, up from 800 in 1985. The CBS provided data that demonstrated that community-based conservation initiatives are a viable option through which conservation objectives can be achieved. The CBS has influenced my current work and interest in exploring co-management agreements as a viable, sustainable solution to protecting biodiversity while simultaneously improving the economic livelihoods of local peoples.

During tours in the rainforest within the CBS, visitors were always amazed at the plethora of uses of plants by the Creole people. I myself, being Creole, became very interested in learning about the traditional uses of plants. It was during this time that I realized that the ethnobotanical knowledge of these plants was rapidly disappearing from my culture because of rapid acculturation and the deaths of medicine men and women. This realization led me to systematically study the ethnobotany of the Belizean Creole in an attempt to record the culture’s use of plants and subsequently preserve their rich botanical history. Besides recording the ethnobotany of the Creoles, I was interested in their distribution and species diversity patterns across Belize and the impacts, if any, that collection and harvesting were having on these species. In a nutshell, my current work and interests stem directly from my early exposure in those areas.

Mongabay: What’s the best way to encourage more Belizeans to become scientists?

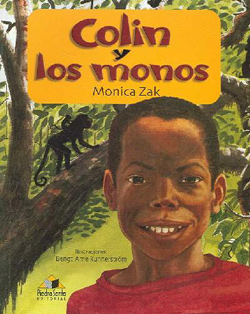

In 1990, a children’s book called “Colin and the Monkeys” was published in Dutch and Swedish. The book chronicled Colin’s efforts to help protect the black howler when he was 9 years old. In 2006, a Spanish version, titled “Colin Y Los Monos“, was released in Guatemala City |

Young: Having strong, creative teacher education programs in the sciences for primary and secondary-level teachers is a necessary first step to excite students in pursuing careers as scientists. Scholarship opportunities for Belizeans to pursue careers in the natural sciences will make it feasible for Belizeans to pursue careers in science. Once the number of scientists increases, younger generations will have role models they can emulate. Most Belizeans, like minorities in the United States, tend to choose career options in business, medicine, law and education with very few pursuing careers in the natural sciences. While this is partly historical, the lack of role models is also a significant factor. Additionally, graduate degrees in the natural sciences are not currently offered in Belize. If Belizeans want to pursue masters or doctoral work in the natural sciences, they must leave Belize to find graduate programs. The lack of national graduate degree programs also limits the present number of people trained as scientists.

Mongabay: What are the biggest challenges facing aspiring Belizean scientists?

Young: Belizean scientists, like many scientists from small developing countries, face a number of challenges that are difficult, but not impossible, to overcome. Foremost among these for Belizean scientists is the absence of a culture of conducting research as well as the research infrastructure to support in-country scholarship. Indeed, most of the research conducted and published on Belize has been conducted by foreigners. None of the educational institutions in Belize are research institutions per say; they are primarily teaching institutions. Consequently, active research labs maintained by faculty conducting research are absent from Belizean tertiary institutions. Recently, there has been an increase in the number of research stations as the number of non-governmental organizations (NGOs) increase in the country. Most of the researchers at these research stations are non-Belizeans. Even though some of these research stations offer Belizean rates, the reduced rates are usually still prohibitive for many aspiring Belizean scientists to afford.

Passion flower (Passiflora sp) in Belize. Photo by Colin Young. |

Secondly, because research in the natural sciences by Belizean scientists is still in its infancy and because there are no educational institutions with active research programs in-country, it is extremely difficult for Belizean scientists to compete internationally to obtain grant money to conduct research in Belize. Most of the funding for research comes from a handful of local and international NGOs currently conducting work in Belize. Even so, most of this funding is now being diverted to the marine realm. Those scientists interested in terrestrial ecosystems find it particularly difficult to secure funding.

Thirdly, because the tertiary institutions are primarily teaching institutions, faculty normally has a very high course load every semester. It is not uncommon for some faculty to teach as many as five courses for the semester. As a result, faculty members have very little time to engage in research. In many ways, the administration of these institutions fails to appreciate the importance of research, particularly because research has never been a priority.

Finally, there is very little investment in research by the government of Belize. Compared to other countries in the region (e.g., Mexico or Costa Rica), the Belizean government investment in natural science research or in infrastructure is miniscule, despite the economic contribution of the protected areas network to the Belize’s economy.

Mongabay: Do you have any advice for students hoping to become involved in conservation?

Young: Based on my experience teaching in Belize, Belizean students are very enthusiastic about becoming involved in conservation. However, this enthusiasm is not directly translated into them pursuing careers in conservation due to the reasons mentioned above (few role models, historical predisposition to other fields, and lack of graduate programs). Also, a factor is the perception that the salary in the conservation field is uncompetitive.

Creole healer holding Quassia amara in Belize. Photo by Colin Young. |

I would advise students interested in pursuing a career in conservation that the field is extremely rewarding notwithstanding its large number of challenges. Being engaged in conservation will introduce students to the current realities and complexities surrounding conservation and force them to examine the inter-relationships that exist between the realities of the Belizean landscape: high poverty, high unemployment, limited personnel, high deforestation rates, paper parks etc., and conservation. The issues that led us to the point where we must now conserve are multifaceted; as such the solutions must be innovative and equally multifaceted. As young Belizean scientists, they can meaningfully participate in this dialogue and contribute to finding solutions to the challenges that Belize is currently facing and will continue to face in the future. As the impact on Belize’s environment becomes more pronounced, we will also need conservationists who can contribute to finding a balance between conservation and development.

Mongabay: What are the current environmental issues in Belize?

Young: Belize is a second smallest country in Central America with a population of only 300,000 people. The country boasts one of the lowest population densities in the region in addition to a remarkably high biodiversity for its size. As a result, many of the pressures that normally emanate from high population density were absent from Belize until recently. However, the tide is turning and unless Belize is able to adequately respond to these challenges in a timely manner, the environment that has been the mainstay of the Belizean economy will be severely impacted.

Chief among the environmental problems in Belize is the rapid rate of deforestation occurring in the country. Belize is currently experiencing a deforestation rate that is twice that of Central America (2.3% vs. 1.2% annually). The riparian deforestation rate is extremely high at over 13% annually. At the current rates of deforestation, Belize will lose most of its forests in as little as 40 years. Prior to the 1950s, the economy of Belize was based primarily on forestry. As a result, most of the forest was spared. Over the last five decades, the country has embraced large-scale agriculture (citrus, bananas, sugarcane) and more recently large-scale aquaculture (shrimp and tilapia farming) at the expense of the forests. Today, rapid and increasing coastal development, illegal logging, and slash and burn agriculture are also contributing to the high deforestation rate. Within the last few years, the issue of illegal logging and farming by Guatemalan immigrants in Belize’s protected areas has become acute. At the time of this writing, over 13,000 acres of land within Belize’s protected areas have been cleared illegally by Guatemalan immigrants. This issue is compounded by the long standing territorial claim over Belize by Guatemala.

Image Copyright 2007 Tony Rath of Tony Rath Photography www.trphoto.com. |

Secondly, solid and liquid wastes pose serious environmental threats to Belize’s Barrier Reef System (a World Heritage Site and the longest barrier reef in the Western Hemisphere, extending approximately 280 km along its Caribbean coast and covering approximately 1,400 km.) in addition to health implications. The inability of the country to properly dispose of solid waste is evident, which leads to the pollution of inland water supply and the coastal zone as pollutants leach from the landfills. Currently, only three population centers have a sewage waste treatment facilities (Belize City, Belmopan [capital] and San Pedro); however, none of them have 100% of the residents connected. Similarly, the country is currently unable to adequately deal with the increasing amounts of industrial waste being produced from citrus, sugar, bananas, tilapia and shrimp farms. Considering that the majority of Belize’s population and industrial activity (e.g., shrimp and tilapia farming) occur in the costal zone, the inability to properly dispose solid waste and properly treat sewage waste pose a continuing and serious threat to the marine ecosystem and the Barrier Reef System.

In 2004, Belize was recognized as a premier ecotourism destination globally. Since then, the country has taken a noticeable shift from embracing ecotourism to one that prefers large-scale mass tourism. Over the last few years, the number of cruise passengers to Belize has surpassed 800,000 visitors with all expectations that a million visitors will soon visit annually. This number of visitors to Belize represents a tripling of the Belizean population of 300,000 people. As a result, the country lacks the appropriate infrastructure (e.g., solid waste and liquid waste) and enforcement mechanism (e.g., monitoring) to deal with number of visitors. Incidentally, the majority of cruise ship passengers visit sites within two hours of Belize City, most of which lack any sewage waste management. This large increase in visitors, coupled with increased coastal development and concomitant removal of mangroves and clearing of littoral forests are having a significant negative impact on the coral reef.

The rising incidence of poverty in environmentally fragile areas is another environmental threat affecting Belize. Currently 33% of Belizeans are below the poverty line. Poverty exacerbates environmental degradation because disadvantage populations have more pressing concerns than implementing conservation practices. Any attempt to conserve the natural environment in these ecologically sensitive areas must include innovative solutions to improve the socio-economic conditions of the communities that buffer these areas.

Lastly, Belize currently suffers from ineffective institutional and legal frameworks that inhibit enforcement of environmental regulations. The enforcement agencies lack financial resources and personnel to enforce regulations. Many of the policies and legislation are outdated and need revision. The recent completion of the National Protected Ares and System Plan to guide the management of protected areas in Belize is a step in the right direction. If implemented, the Policy and System Plan will remedy many of the institutional and legal issues, including the removal of “ministerial discretion,” a loop-hole that allowed ministers to de-reserve protected areas. Other environmental issues include illegal harvesting of flora and fauna, illegal hunting, and the increase in the introduction of invasive species.

Mongabay: What is your outlook for the Belizean forests?

Young: Unless a multi-sectoral approach that seeks to find a sustainable balance between development and conservation is identified, adopted, and implemented, my outlook for Belizean forests is bleak. With a population growth rate of 2.7% year and a fertility rate of 4.2 children per woman, the Belizean population will double to 600,000 in only 27 years. Coupled with an already very high deforestation rate, increasing incidence of poverty, and increase demand for forest products, Belize’s forests will face tremendous pressures. According to the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO), pressures on Belize’s forest are expected to increase by 20% in the next two decades. Currently, illegal logging poses a serious but insidious threat to Belize’s forests because of the subsequent fragmentation of large tracks of forests that result after logging. Based on available literature, nearly 60% of all the lumber in Belize is harvested illegally. Besides the removal of trees, logging roads provide access to farmers and cattle ranchers who contribute to the deforestation.

Xunantunich Mayan Ruin. Photo by Colin Young. |

In 2002, sweet crude was discovered in western Belize. This fledgling oil industry in Belize, initially greeted with much enthusiasm, now poses a new threat to Belize’s forests. Oil exploration licenses have already been issued for a significant portion of Belize’s land and sea. Furthermore, when the geology and petroleum map is overlaid on the protected areas map, the majority of these potential oil reserves occur within protected areas. With the current price of oil, there will be tremendous pressure and temptation by the governments to make the necessary legal amendments to the protected areas policy to allow oil exploration and production at the expense of further destruction of forests and potential pollution of watersheds via oil spills.

Presently, 26.2% of Belize’s territory (land and sea) is under some form of protection with 34% protected terrestrially. However, only 13% of the protected areas in Belize are reserved strictly for the conservation of biodiversity; the majority of the protected areas are extractive reserves that allow the removal of flora, timber, and fauna. To make matters worse, some of Belize’s parks are also paper parks with no on-the-ground management. Unless these protected areas are managed in an integrated manner in collaboration with all their stakeholders, these protected areas themselves face numerous challenges in the near future.

Recently, the Association of Protected Areas Management Organizations (APAMO), the Belize Audubon Society and a host of other international and local NGOs and other stakeholders successfully pressured the Government of Belize to reverse its decision to de-reserve a portion of a World Heritage Site in the Bacalar Chico Marine Reserve. This type of activism and positive action by stakeholders gives me hope that Belizeans can rise to the challenge and reverse the recent trends that are adversely impacting the environment. Just to “talk the talk” is no longer sufficient; we must truly “walk the walk,” and find ways to put ideas into action.

Mongabay: Do you see climate change as a significant threat to Belize or are there more pressing concerns?

Young: In the short term, the environmental issues such as high deforestation rates, inability to properly deal with solid and liquid waste, rising poverty rates and escalating coastal development are more pressing concerns than climate change. However in the medium term, climate change poses a serious and significant threat to Belize. The majority of Belize’s population live in the coastal zone; consequently, rising sea levels, as a result of climate change, can have severe impacts of costal populations, including the largest population centers that are near sea level. Rising sea levels and sea temperatures may also negatively impact the Barrier Reef system that supports a thriving fisheries and tourism industry in Belize with devastating impacts on the Belizean economy. Also, the constant threat of hurricanes, expected to increase in both frequency and intensity due to climate change, remains a real threat to Belize’s coastal populations, coral reefs, and protected areas. Though tropical ecosystems may be resilient and have the ability to bounce back after these types of intermediate disturbances, the concomitant anthropogenic impacts may decrease the resiliency of these ecosystems.

Mongabay: What is the best way to manage the forest resources of Belize?

Young: There is no best way’ to manage the forest resources in Belize because these forest resources face a number of different threats based on their designation (e.g., forest reserve vs. wildlife sanctuary), location, access, management capacity, and financial resources to name a few. What is apparent is that forest resources in Belize need to be managed in a more holistic and transparent manner using best practices and best management guidelines and criteria. Empowering local communities and local people, where appropriate, to become stewards and co-managers of forest resources is also paramount. The experience and successes of the Community Baboon Sanctuary and the Toledo Institute for Development and Environment (TIDE) among others initiatives in Belize, demonstrate that co-management of forest resources is a viable and sustainable strategy for managing natural resources for the long term. However, the government cannot continue to view co-management agreements as a means to absolve them of any management and financial responsibility. The capacity of the co-managers must also be increased to make management effective. Lastly, the government needs to allocate the necessary financial resources to allow better management and enforcement of Belize’s forest resources in addition to improving the human capacity to better manage the protected areas network of Belize. The NGOs and private association of reserves also have a role to play by contributing their expertise and financial resources to improve the system as a whole. Forest resources must be seen for more than just the trees. Their contribution and importance in providing ecosystem services must be recognized, appreciated, and factored into the decision-making process.

Mongabay: What’s the best way to ensure that local people benefit from conservation?

Young: The most sustainable way to ensure that local people benefit from conservation is to educate them to recognize the importance and necessity of conservation. By empowering them to become stewards of their environment, local people will become an integral part of the decision-making process. In cases where cultural lifestyles conflict with conservation objectives, amicable solutions must be found that provide viable livelihood alternatives to those individuals and/or communities. Recognizing that deteriorating or poor socio-economic conditions are drivers of environmental degradation, any successful conservation initiative involving local people must be first cognizant of these factors and attempt to empower people by providing them with the necessary skills and know-how required to improve their conditions. Unless the socio-economic conditions are improved, conservation will never be a priority in the lives of local people.

Mongabay: Can eco-tourism alone support a community? Does ecotourism provide returns on par with extractive industries like logging and mining?

Young: Because ecotourism and other forms of tourism are so seasonal and dependent of a number of national and international factors, including natural disasters, it is extremely difficult for ecotourism alone to support a community. Instead, communities should seek to diversify their economic base to supplement the economic contribution from ecotourism. Even in communities in which ecotourism is the primary income earner, there is immense disparity between those who benefit directly from ecotourism. This disparity often leads to annoyance and antagonism among the population not directly benefiting from ecotourism towards tourism. Unless mechanisms are identified to distribute the benefits of ecotourism back into the communities supporting the ecotourism destination, this kind of disparity will always exist.

Sunset in Hopkins Village. Photo by Colin Young. |

Yes, I do believe that ecotourism, if managed properly, has the potential to provide returns higher than those obtained from extractive reserves such as logging and mining. While logging and mining are essentially finite industries, ecotourism can essentially be a renewable resource that appreciates over time. However, ecotourism per se does not exclude other type of land use (e.g., logging). If the logging is managed sustainably, utilizing sustainable forestry management techniques both can co-exist and contribute to improving the livelihood of communities. The success of these initiatives hinges on the capacity of the communities to manage, monitor, and enforce environmental regulations. Secondly, both logging and mining require large start up costs and investment that prevent local people from owing these industries. As a result, they are reliant on outside investors who normally control the decision-making process. Conversely, ecotourism can be owned and managed locally with local people in charge of the decision-making.

Mongabay: You’ve been involved with a conservation initiative known as the Community Baboon Sanctuary — what made this project a success?

Young: Established in 1985 to protect the endangered Black Howler Monkeys, the Community Baboon Sanctuary (CBS) was the first experiment in grass roots conservation in Belize. The very premise of the sanctuary was novel: membership and participation in the sanctuary was voluntary; all the lands within the sanctuary were private or leased by villagers; adherence to suggested land management techniques was voluntary; local people were consulted and participated in the decision-making process; initial management of the sanctuary was locally controlled. These factors were instrumental and contributed to the success and survival of the CBS. However, the initiative had many challenges that threatened its survival in its formative years. In hindsight, it became apparent that the management capacity of the sanctuary staff lacked the necessary capacity in areas of protected areas management, financial accountability and transparency, and fundraising in the early years of management. Equally important, the initial management committee consisted of all men thereby excluding women in the decision-making process. Ironically, the most effective and transparent management the CBS has ever seen was achieved under the management of an all Women Conservation Group who currently manages the CBS. They have built their capacity in small business management, protected areas management, hospitality training, sustainable farming, computer literacy, grant writing to make them better managers. These women have been able to attract over $120,000 in grant money to assist in the management of the CBS and build infrastructure (e.g., community restaurant, library and computer lab; maintain nature trails, and capacity building). They serve as a testament to the important role women must play in conservation.

Colin with Catopsis nitida in Belize. Photo by Bruce Holst of the Marie Selby Botanical Gardens. |

More importantly, the management committee also works diligently to empower members of the Sanctuary through the provision of training, start-up funding for small scale projects (e.g., basket weaving; tilapia farming, embroidery) to improve the socio-economic conditions of members of the Sanctuary. Even so, ensuring equitable distribution of the benefits from ecotourism to all member villages remains one of the greatest challenges facing the Sanctuary, especially since each village differs in the number and types of attractions to tourist. Today, the Sanctuary receives about 15,000 visitors annually who provide economic benefits to villagers via bed and breakfast accommodations, horse-rentals, canoe rental, tilapia farming. Additionally, villagers are employed as tour guides. In summary, the Sanctuary has been successful because of its grassroots and voluntary nature and the ability to the Sanctuary to generate economic opportunities that provide alternative livelihood opportunities for its members.

Mongabay: What can indigenous use of medicinal plants and other forest resources teach us about conservation?

Young: Indigenous peoples have empirically experimented with medicinal plants and other forest resources for hundreds, and in some cases, thousands of years. As such, these groups have identified sustainable use strategies (e.g., agroforestry) and harvesting techniques that maximize land use and improve crop yield while simultaneously reducing the reliance of artificial herbicides and pesticides. Contemporary societies who are serious about sustainable development can learn much by understanding and applying some of these strategies, many of which, if employed, will reduce some pressures on the environment. For example, the harvesting of non-timber forest products (leaves for thatching or sticks for construction) among the Creoles traditionally occurred during the full moon. According to elders, products harvested during the full moon are significantly more durable and herbivory resistant than those same products harvested on other parts of the lunar cycle. Vogt et al. (2002) established a scientific link between the timing of harvesting NTFPs by indigenous people using lunar cycle and the production of anti-herbivory compounds, which increased their resistance to herbivory, thereby increasing durability. For species that are already being over harvested (e.g., Sabal mauritiiformis) to meet escalating demands, knowing the right time to harvest these leaves can reduce the harvesting pressures to collect new leaves because the existing leaves will last much longer.

Likewise, forest resources provide a number of non-timber forests products that if harvested sustainably and marketed can contribute to poverty reduction of local communities as well as provide economic incentives for local people to continue protecting and conserving forests.

Lastly, medicinal plants play an integral role in the lives of Belizeans where 75% of the population relies on traditional medicine because it is accessible, affordable, and available. Thus, these plants play an important role in maintaining the health of local people. A healthy population is a prerequisite for engaging local people in conservation. It is imperative that we continue to protect the forest habitats in which local people access medicinal plants and other forest sources so that they can continue to meet their needs; by so doing, these same forests will provide habitats for other species.

Mongabay: What can people do to help conservation efforts in Belize?

Young: International NGOs have a large role to play in assisting conservation efforts in Belize. However, their role must be limited to technical transfer of expertise and capacity building among the local NGOs, government departments, and local stakeholders to allow them to effectively and efficiently manage Belize’s protected areas and natural resources. The agenda of international NGOs must become less esoteric and more responsive to the socio-economic, political and environmental challenges currently facing the country. Rather than each NGO having its own mandate and conservation priorities, they must improve coordination and collaboration and pool their financial and expertise to achieve the most urgent conservation objectives.

Secondly, both national and international scientists must do more to engage the public and especially students to become more excited about nature and conservation in order for us to build a cadre of trained Belizean scientists. Internship opportunities both locally and foreign will expose these students to new horizons and introduce them to field of conservation. Bioblitz-type activities with adequate media coverage and student involvement can showcase the work and importance of biodiversity to the public. Belizeans must also begin to demand that the Government invest more money in natural science research and infrastructure in addition to ensuring that public agencies (e.g., forestry department) have the capacity, personnel, and financial resources to adequately manage Belize’s natural resources.

Though much research is conducted in Belize in a variety of disciplines and taxa, very rarely is the research easily available and accessible to students, scientists, conservation stakeholders and policy makers. Subscribing to academic journals is prohibitive for most institutions and or small organizations in Belize. Consequently, the findings from research done in Belize are rarely utilized in the management and decision-making of protected areas or in education of students or persuading politicians. Recently, the ministry of natural resources launched the Clearing House Mechanism (CHM) website as part of the commitment to the Convention of Biological Diversity. This site should serve as a repository for research papers on Belize. Though the CHM is very welcomed and timely, a niche exists for NGOs to serve as intermediaries between scientists and the public, including conservation managers and stakeholders, to essentially translate the scientific findings into lay people language so as to allow comprehension and incorporation, where appropriate, in management of Belize’s resources.

Lastly, lack of funding for in-country research remains a serious impediment to aspiring Belizean scientists. Funding, utilizing a number of fundraising approaches as well as the expertise of the conservation community, must be identified and earmarked for applied natural science based research that can provide scientific arguments that can be factored into policy development and decision making. In the meantime, individuals’ donations to worthy Belizean organizations actively engaged in conservation will continue to go along way in protecting Belize’s natural resources.