Scientists find treatment for killer frog disease

Scientists find treatment for killer frog disease

mongabay.com

October 29, 2007

Discovery offers hope for captive breeding programs, but outlook still poor for amphibians

New Zealand scientists have found a treatment for a disease blamed for the death of millions of amphibians worldwide, according to a report from BBC News. However, at best, the cure would only be applicable to captive populations. The disease is killing many amphibians in apparently pristine habitats.

Chytridiomycosis, caused by a parasitic chytrid fungus known as Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, is blamed for one-third of amphibian extinctions since 1980. Although researchers don’t yet know the origin of the fungus (they suspect that it might be the African clawed frog, a species that has been shipped around the world for research purposes), the fungus is highly transmissible and spreading fast: the fungus is now found on at least four continents and was recently reported for the first time in Japan. While scientists debate whether climate change or other environmental factors are the primary driver of the disease, few dispute that the many amphibians populations are at great risk of extinction unless drastic measures are taken. Accordingly, last year a coalition of zoos, aquariums, and botanical gardens announced a $400 million drive to establish captive breeding programs for the most threatened species. The effort, dubbed the Amphibian Ark, seeks to house 500 individual frogs from each of 500 species in biosecure facilities around the world.

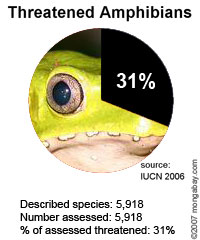

Scientists say amphibians — cold-blooded animals that include frogs, toads, salamanders, newts and caecilians — are under grave threat due to climate change, pollution, and the emergence of a deadly and infectious fungal disease, which has been linked to global warming. According to the Global Amphibian Assessment, a comprehensive status assessment of the world’s amphibian species, one-third of the world’s 5,918 known amphibian species are classified as threatened with extinction. Further, more than 120 species have likely gone extinct since 1980. Scientists say the worldwide decline of amphibians is one of the world’s most pressing environmental concerns; one that may portend greater threats to the ecological balance of the planet. Because amphibians have highly permeable skin and spend a portion of their life in water and on land, they are sensitive to environmental change and can act as the proverbial “canary in a coal mine,” indicating the relative health of an ecosystem. As they die, scientists are left wondering what plant or animal group is next. |

While the Amphibian Ark offers a means — if a costly one — to protect captive frogs from the disease, there are still concerns about contamination, which has been a problem in past efforts. The finding that Chloramphenicol–commonly used as an eye ointment for humans–kills Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, potentially offers another way to disinfect frogs and possibly help them build resistance to the disease.

Still applying the treatment–which requires that frogs be immersed or dabbed with Chloramphenicol–in wild populations on the scale necessary to control the outbreak would be a massive undertaking. Another solution to chytridiomycosis may come from research presented in May by James Madison University professor Reid N. Harris at the General Meeting of the American Society for Microbiology in Toronto. Harris reported that Pedobacter cryoconitis, a bacteria found naturally on the skin of red-backed salamanders, wards off the deadly chytridiomycosis fungus–at least in the lab.

“The exciting aspect is that we identified at least one bacterium from the skin that in both the dish and on the salamander aids the healing process

one species of bacteria which you could tentatively view as a probiotic,” said Harris, while warning that extensive testing was still needed to see whether the bacteria works in other environments.

|

However even if these efforts are successful in warding off chytridiomycosis, they will not be a magic bullet — there are other factors behind the global decline in amphibians. A study published in April in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences reported a precipitous decline in amphibian populations in a chytridiomycosis-free rainforest in Costa Rica. Similar research elsewhere has documented die-offs in areas otherwise unaffected by the disease. In fact, some researchers suggest the outbreak of chytridiomycosis is merely a symptom of a much broader problem for amphibians, one that may be linked to climate change, increased UV radiation, or pesticide use. Because amphibians have highly permeable skin and spend a portion of their life in water and on land, some scientists say that amphibians are especially sensitive to environmental change and can act as the proverbial “canary in a coal mine,” indicating the relative health of an ecosystem. In other words, amphibians are not out of the wood yet.