Are the economic benefits of palm oil exaggerated?

Does palm oil alleviate rural poverty in Malaysia?

Rhett A. Butler, mongabay.com

October 24, 2007

While it is often argued that the economic benefits of oil palm plantations outweigh the environmental costs of converting biodiverse ecosystems to monocultures, new analysis suggests that the role of plantations in reducing rural poverty may be overstated.

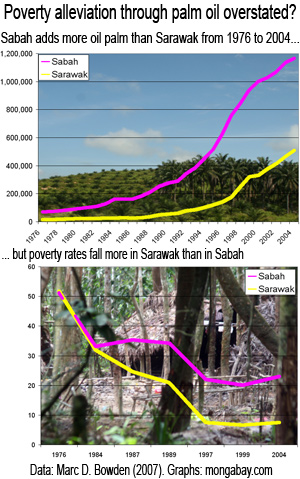

Examining poverty rates and oil palm expansion in the Malaysian states of Sarawak and Sabah on the island of Borneo, researcher Marc D. Bowden found that despite substantially lower coverage of oil palm plantations, Sarawak saw a greater reduction in poverty rates over the past three decades than neighboring Sabah. In Sarawak, where oil palm plantation cover expanded from 0.12 percent of the land area in 1976 to 4.08 percent in 2004, the proportion of the population living below the poverty line fell 85 percent from 51.7 percent to 7.5 percent in the same period. Meanwhile in Sabah, where oil palm plantation cover grew from 0.95 percent in 1976 to 15.81 percent in 2004, poverty rates dropped 55 percent from 51.2 percent to 23 percent.

Oil palm is the world’s most productive oilseed. Palm oil is derived from the plant’s fruit, which grow in clusters that may weigh 40-50 kilograms. A hundred kilograms of oil seeds typically produce 20 kilograms of oil, while a single hectare of oil palm may yield 5,000 kilograms of crude oil, or nearly 6,000 liters of crude oil that can be used in biodiesel production. |

“Proponents of palm oil development claim that their crop is a significant driver of development. But if this was true, one would expect a far greater reduced rate of poverty in Sabah than has occurred in Sarawak,” writes Bowden. “It would be unwise to assume that the palm oil industry has had no positive impact on reducing poverty in Sabah, but it is clear that any causal relationship is not as strong as is broadly assumed.”

Bowden says that rural populations in Sabah have failed to benefit from oil palm expansion partly because plantation owners primarily employ workers from the Philippines and Indonesia. He further notes that in 2005 only 6.3 percent of Sabah’s total palm oil estate was controlled by small landholders.

“It is often heard that if palm oil had not been established across eastern Sabah, an alternative crop would have. But would an alternative crop have monopolised as much land, had such a low impact on reducing poverty, or had such an adverse impact on rare and endangered species?” he asks, while noting that oil palm expansion has put Sabah’s most charismatic species at risk of extinction.

“Rapid palm oil development has also significantly impacted Sabah’s natural heritage as exemplified by its mammalian megafauna. Large, wide-ranging mammal species with low reproductive rates have been severely impacted by the unplanned development of palm oil in the state’s east. The ranges and habitat of three species in particular–the Bornean rhino (Dicerorhinus sumatrensis harrissoni), Bornean pygmy elephant (Elephas maximus borneensis), and the Orang-utan (Pongo pygmaeus mori)–have significantly contracted and/or been fragmented and/or been degraded over the past thirty years.”

Given the apparent failure of the palm oil industry to reduce poverty in Sabah relative to Sarawak, Bowden recommends several steps for future development, including improving oil yields per hectare from the present estate; clamping down on illegal immigration; providing universal primary and secondary education; reducing illiteracy rates among children and adults; encouraging greater government transparency by dealing severely with corruption involving government officials and employees; and improving rural infrastructure, including roads, water, sanitation, and electricity.

“Although the decline in both [Sabah and Sarawak] was concurrent with expansion of their respective palm oil estates, Sarawak converted less than half the area of land converted to palm oil in Sabah (493,000 ha as opposed to 1,095,000 ha), and in doing so monopolised less than a third of the proportion of total land area utilised in Sabah (4% as opposed to 15%),” writes Bowden. “Sabah’s progress toward poverty reduction is… significantly lagging behind every other Malaysian state.”

CITATION: Bowden, M. (2007). PALM OIL, POVERTY AND CONSERVATION IN SABAH.

Unpublished.

MORE ON PALM OIL

Environmentalists and palm oil producers should work together

(9/25/2007) Environmentalists and palm-oil producers are increasingly at odds. Greens groups say palm oil is driving the conversion of tens of thousands of hectares of peatlands and lowland forest in Indonesia, putting wildlife at risk, increasing the vulnerability of forests to fires, and triggering large emissions of greenhouse gases.

Indonesia’s peatlands may offer U.S. firms global warming offsets

(8/29/2007) The following is modified version of a letter I’ve used to pitch U.S. companies on the concept of carbon finance in Indonesia’s peatlands. Discussions are slow and the critical December U.N. climate meeting is fast approaching, so I’m posting this as a tool to help you get American firms interested in avoided deforestation offsets. Please feel free to use, modify, and distribute this letter widely.

Could peatlands conservation be more profitable than palm oil?

(8/22/2007) This past June, World Bank published a report warning that climate change presents serious risks to Indonesia, including the possibility of losing 2,000 islands as sea levels rise. While this scenario is dire, proposed mechanisms for addressing climate change, notably carbon credits through avoided deforestation, offer a unique opportunity for Indonesia to strengthen its economy while demonstrating worldwide innovative political and environmental leadership. In a July 29th editorial we argued that in some cases, preserving ecosystems for carbon credits could be more valuable than conversion for oil palm plantations, providing higher tax revenue for the Indonesian treasury while at the same time offering attractive economic returns for investors.

|

Environmental concerns mount as palm oil production grows

(5/15/2007) The booming market for palm oil is driving record production but fueling rising concerns over the environmental impact of the supposedly “green” bioenergy source. The two leading producers of palm oil, Malaysia and Indonesia, have rapidly expanded palm oil production in recent years, often at the expense of biodiverse rainforests and carbon-rich peatlands that store billions of tons of greenhouse gases. Environmentalists say that due to these factors, burning of palm oil can at times be more damaging the global climate than the use of fossil fuels.

Dutch plan restricts biofuels that damage environment

(4/29/2007) The Netherlands has proposed a system to reduce the environmental impact of biofuels production. The country becomes the first in the world to establish such guidelines. Environmentalists have expressed increasing concern for the establishment of energy crops in biodiverse and carbon-rich ecosystems like the peatlands of Indonesia and the Amazon rainforest. They say that conversion of these forests for oil palm and soybeans is threatening endangered species and worsening global warming. Further, they warn, demand for such biomass energy products is driving up prices for food crops.

Palm oil doesn’t have to be bad for the environment

(4/4/2007) As traditionally practiced in southeast Asia, oil palm cultivation is responsible for widespread deforestation that reduces biodiversity, degrades important ecological services, worsens climate change, and traps workers in inequitable conditions sometimes analogous to slavery. This doesn’t have to be the case. Following examples set forth by the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil and firms like Golden Hope Plantations Berhad, a Malaysian palm oil producer, oil palm can be cultivated in a manner that helps mitigate climate change, preserves biodiversity, and brings economic opportunities to desperately poor rural populations.

Eco-friendly palm oil could help alleviate poverty in Indonesia

(4/3/2007) The Associated Press (AP) recently quoted Marcel Silvius, a climate expert at Wetlands International in the Netherlands, as saying palm oil is a failure as a biofuel. This would be a misleading statement and one that doesn’t help efforts to devise a workable solution to the multiplicity of issues surrounding the use of palm oil.

Why is palm oil replacing tropical rainforests?

(4/25/2006) In a word, economics, though deeper analysis of a proposal in Indonesia suggests that oil palm development might be a cover for something more lucrative: logging. Recently much has been made about the conversion of Asia’s biodiverse rainforests for oil-palm cultivation. Environmental organizations have warned that by eating foods that use palm oil as an ingredient, Western consumers are directly fueling the destruction of orangutan habitat and sensitive ecosystems. So, why is it that oil-palm plantations now cover millions of hectares across Malaysia, Indonesia, and Thailand? Why has oil palm become the world’s number one fruit crop, trouncing its nearest competitor, the humble banana? The answer lies in the crop’s unparalleled productivity. Simply put, oil palm is the most productive oil seed in the world. A single hectare of oil palm may yield 5,000 kilograms of crude oil, or nearly 6,000 liters of crude.