Climate change will impact U.S. economy

Climate change will impact U.S. economy

mongabay.com

October 16, 2007

Climate change will have a significant economic impact on the United States, reports a new study published by researchers from the University of Maryland.

The report, The U.S. Economic Impacts of Climate Change and the Costs of Inaction, aggregates and analyzes previous economic research in order to develop a better estimate of the costs of climate change.

“The range of climatic changes anticipated in the United States — from rising sea levels to stronger and more frequent storms and extreme temperature events — will have real impacts on the natural environment as well as human-made infrastructure and their ability to contribute to economic activity and quality of life,” write the authors. “These impacts will vary across regions and sectors of the economy, leaving future governments, the private sector and citizens to face the full spectrum of direct and indirect costs accrued from increasing environmental damage and disruption.”

|

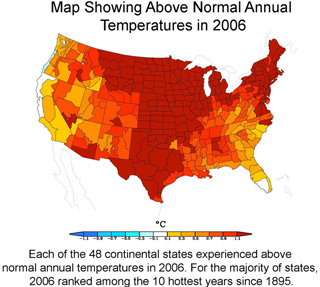

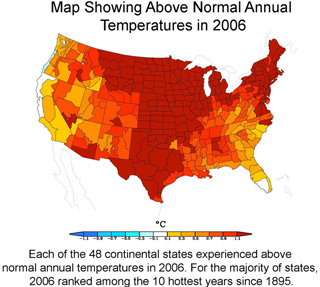

Map showing above normal annual temperatures in 2006. Courtesy of NOAA.

|

The authors say there has been limited research on the long-term costs of addressing the economic impacts of climate change on the agricultural, manufacturing and public service sectors. They argue that inaction could steeply increase the cost of adaptation.

“Climate change will affect every American economically in significant, dramatic ways, and the longer it takes to respond, the greater the damage and the higher the costs,” said lead researcher Matthias Ruth, director of the University of Maryland’s Center for Integrative Environmental Research. “The national debate is often framed in terms of how much it will cost to reduce greenhouse gases, with little or no consideration of the cost of no response or the cost of waiting. Review and analysis of existing data suggest that delay will prove costly and tip the economic scales in favor of quicker strategic action.”

The report concludes:

- Economic impacts of climate change will occur throughout the country.

- Economic impacts will be unevenly distributed across regions and within the economy and society.

- Negative climate impacts will outweigh benefits for most sectors that provide essential goods and services to society.

- Climate change impacts will place immense strains on public sector budgets.

- Secondary effects of climate impacts can include higher prices, reduced income and job losses.

The report suggests that since the economic effects of climate change are still poorly known, policymakers should support “an immediate, large-scale, coordinated research effort.”

|

The U.S. Economic Impacts of Climate Change and the Costs of Inaction.

|

“We’ve connected the dots as far as the data would allow,” said Ruth. “Now that the climatological picture about future conditions is becoming clear, research needs to provide the socioeconomic information to guide policy. This study offers the first comprehensive analysis. Next, we will need to carry out sector and region-specific research using new methodology. The traditional, narrow micro-economic approach used in current studies is simply not suited to this task.”

“The potential costs of the climate impacts are so staggering that this would surely be a wise investment,” he continued. “Yet current research on the full range of economic costs is sufficient to conclude that delayed action (or inaction) on global climate change will likely be the most expensive policy option. A national policy for immediate action to mitigate emissions coupled with efforts to adapt to unavoidable impacts will minimize the overall costs of continued climate change.”

The U.S. Economic Impacts of Climate Change and the Costs of Inaction

Regional notes from the report

West

Similar to other regions, meeting the competing needs and uses for water resources will be a major challenge as decreased winter snowpack contributes to changes in water flow, both in quantity and timing. Although the picture is incomplete because of data limitations, a valuable glimpse of the extent to which climate change will affect these economic sectors can be gleaned from the summary below.

Water System and Agriculture

Major climate change models predict winter snowpack will decline and snowmelt will occur earlier, which will result in greater runoff. The ability to store water in aquifers for later withdrawal may be compromised. Simultaneously, the demand for water is rising in the region. Ground-water withdrawals increased significantly in recent years in many Western states — 324% in Nevada, 147% in New Mexico, 208% in Utah, and 52% in California. Meeting increased urban demand for water in California is estimated to cost the state $316 million to $5 billion per year by 2085.

Water shortages will force farmers in the area to fallow their lands. The estimated annual loss to the agricultural sector around the Central Valley will be $278.5 to $829 million, depending on the dryness of year. The estimated economy-wide loss for the Central Valley region is expected to reach up to $6 billion during the driest years.

Decreased supplies of water are expected to diminish the value of farmland by around 36%, translating into a loss of $1,700 per farm.

The value of wine production in California is $3.2 billion, which may be compromised, as grape quality will likely diminish with higher temperatures.

The decline in dairy cow productivity is correlated with higher temperatures, as well. An annual loss of $287-902 million is expected to this $4.1 billion industry in California.

Other impacts

Coastal infrastructure will be affected by sea level rise and flooding. For example, to protect the San Francisco Bay Area and the stretch of coast south of Santa Barbara from a 3.28 feet (1 meter) rise in sea level, an initial investment of $1.52 billion, plus $152 million in annual maintenance costs, will be required. The probability of a major flood event there is predicted to increase to a 2-in-5 chance of an event occurring in the next 50 years.

Energy infrastructure will also be affected. Under extreme heat events, the increase in net energy expenses in California is expected to rise by $2 to $18.7 billion by 2100. Additionally, energy generated from hydropower sources will have to be reduced by approximately 10% because of lower water levels, costing $3.5 billion annually for California.

Timber yields are expected to decrease by 18% for mixed conifers and 30% for pine plantations in California. An expected increase of 55% in forest fires will additionally stress this and other sectors. The 1991 Oakland fire caused losses of about $2.2 billion (in 2005 dollars), and the 2003 wildfires in San Diego and San Bernardino Counties damaged $2 billion worth of property and infrastructure

The recreation industry is also likely to suffer. Skiing, for example, is worth around $1 billion for the entire region.

Pacific Northwest

The greatest threats from climate change come from increased temperatures and decreased precipitation in summer, contributing to water shortages and increased forest fires. Although the picture is incomplete because of data limitations, a valuable glimpse of the extent to which climate change will affect these economic sectors can be gleaned from the summary below.

Water supply

Declining snowpack levels would lead to a 10% reduction in annual average stream flows and reduced peak spring flows across the region. One study suggests that by 2090 snowpack will fall 72% below the 1960-90 average, which would not only diminish water supplies but could lead to a loss of lower elevation skiing destinations. The secure supply of water to the region may fall by as much as 6.1 million gallons per day for every ten years of climate change.

As supplies decrease, water demand will continue to grow because of continued population and economic growth in the region. Growth in demand will be exacerbated by climate change, which will add another 5-8% on to the already large 50% projected increase in demand for summer municipal water supplies by 2050. All together, impacts from climate change will alter water storage in the state by 1.3 billion gallons annually. With the projected demand for water increasing by 1.5 billion gallons annually, a 2.8 billion gallon per year increase in storage capacity will be required. This number could jump to 5.5 billion gallons in a particularly dry year. Combined with increases from population growth, the total increase in water demand may be as large as 8.0 billion gallons in 2020 and 9.6 billion gallons in 2040.

Other impacts

Forestry is expected to be greatly impacted as increased incidence of fire is expected. Already climate change effects, such as increases in spring and summer temperatures and earlier melting of snowpacks, contributed to the six-fold spike in the area of forest burned since 1986, compared with the 1970-1986 period. Moreover, the average duration of fires increased from 7.5 to 37.1 days since 1986. In 1987, 1.2 million acres of forest burned throughout the US, the first time since 1919 that more than one million acres burned in one year. As a result of similar fires in 1988, 1994 and 1996, and a record 2.14 million acre fire in 2000, fire suppression costs increased to $1 billion, or about $480 per acre.

A 50% increase in the number of acres burned is expected by 2020, and a 100% increase by 2040, raising the fire suppression bill to $124 million.

The region’s coastal infrastructure is likely at risk from sea level rise, the effects of which will be compounded by land subsidence. Currently, land in the Puget Sound is subsiding 0.3-0.8 inches per year. A two-foot rise in sea level would inundate approximately 56 square miles in Washington, affecting more than 44,000 people. This kind of change could happen in Tacoma within the next 50 years. In order to protect coastal settlements, expensive infrastructure will need to be designed and re-designed, built and re-built. One estimate of the costs of redesigning the Alaskan Way seawall increases project costs 5-10% ($500 million) when protection from sea level rise is considered.

Agriculture in the Pacific Northwest may benefit from a longer growing season, but these benefits may be offset by higher maximum temperatures and water shortages. Expected annual crop losses from water shortages are projected to rise from $13 million at present to $79 million by mid-century (1.4 to 8.8% of $901 million total output).

Human health may be affected by increased air pollution that increases asthma and other respiratory diseases; warmer weather may also support the introduction of infectious diseases into previously unaffected areas.

The Great Plains

Despite a predicted increase in precipitation, higher temperatures throughout the region are likely to result in net soil moisture declines because of water loss through evaporation. Competing uses for water could result in re-prioritization of land use and will greatly impact some economic sectors. Although the picture is incomplete because of data limitations, a valuable glimpse of the extent to which climate change will affect these economic sectors can be gleaned from the summary below.

Agriculture and Water

The agricultural sector in the region contributes $22.5 billion annually in market value of products — 35% of which is attributed to crops and the rest to livestock. The consumptive demand for water for crops (especially grass and alfalfa) may increase by 50% by 2090, straining water resources in the region. One study estimated that net agricultural income will decrease by 16-29% by 2030 and by 30-45% by 2090 because of conflicting water uses around the San Antonio Texas Edwards Aquifer region. If similar trends hold for the entire region, the agricultural sector stands to lose $3.6-$6.5 billion annually until by and $6.75-$10.13 billion annually by 2090.

A year-long drought in 1995 cost the Southern Great Plains agricultural sector $5.81 billion. Stressed ecosystems are more susceptible to invasive species; control costs and weed-associated losses due to invasives amount to $15 billion annually nationwide. The region is home to 23.4% of nation’s crop and animal production. Under the assumption that costs to control invasive species are distributed evenly throughout the country, the region expends $3.51 billion in annual invasive species control costs. This figure may increase dramatically, as damaging invasive species migrate north with warmer temperatures.

The Southern and Plains regions are likely to experience a decline in productivity totaling as much as 70% for soybeans and 10-50% for wheat; although crops in other areas may temporarily increase their yields.

An additional burden on the agricultural sector may be an increased resilience of insects to pesticides. Pesticide use and the associated costs are estimated to increase by 10-20% for corn; 5-15% for potatoes; 2-5% for cotton and soybeans; and 15% for wheat.

Other impacts

Water demand for municipal uses will likely increase as regional temperatures continue to rise. A study of the San Antonio Texas Edwards Aquifer region estimates municipal water demand to increase by 1.5-3.5%. As supplies of freshwater diminish, quality of water is likely to suffer. Increased contamination of water has been estimated to raise the cost of water treatment by 27% from around $75 to $95 per million gallons in Texas.

Higher incidences of severe weather events are likely to cause major damage to the region’s infrastructure. For example, a 1999 outbreak of tornadoes in the Great Plains caused $1.16 billion in damages and 54 deaths; and an extreme flooding event in 1998 in southeast Texas inflicted $1.16 billion in damages and caused 31 deaths.

Midwest

A big concern in the region is drought-like conditions resulting from rising temperatures, which increase evaporation and contribute to decreases in soil moisture and reductions in lake and river levels. Although the picture is incomplete because of data limitations, a valuable glimpse of the extent to which climate change will affect these economic sectors can be gleaned from the summary below.

Manufacturing and Shipping

Approximately $3.4 billion and 60,000 jobs rely on the movement of goods within the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence shipping route annually. Water levels are expected to drop significantly, necessitating dredging. An estimated 7.5-12.5 million cubic yards of sediment will need to be dredged annually at a cost of $85-$142 million

System connectivity is predicted to become 25% impaired, causing a loss of $850 million annually. Increased incidences of drought will likely place an additional stress on the water conveyance system. For example, a 1988 Midwest drought cost the region over

$49 billion, in part because riverine commercial shipping had to be replaced by more expensive railroad transport due to reduced water levels in the Mississippi River.

Other impacts

Forestry is an integral part of the economic structure in the Midwest. Over 90% of forestland is used for commercial forestry, resulting in economic activity valued at $41.6 billion. The sector employs 200,000 people and produces $27 billion in forest products. Many of the economically valuable timber species — aspen, jack pine, red pine, and white pine – may be lost due to warming of the climate. The virgin pulping/wood fiber industry may be eliminated entirely as the forest cover landscape shifts toward oak and hickory species.

Potentially negative impacts are expected to the $5.7 billion dairy industry, since milk production is temperature-sensitive and is reduced once temperatures advance beyond a certain threshold.

The agriculture sector also may experience losses similar to the 1988 drought, which cut production of grain by 31% and production of corn by 45%.

Outdoor recreation will likely suffer as forest cover matrices shift. In Michigan, Minnesota and Wisconsin alone, $4.7 billion was spent in 1996 on hunting, and bird-watching generates $668 million in retail sales and supports 18,000 jobs.

Skiing is likely to be affected as well. Lighter than usual snowfall during the 1997-1998 season resulted in business losses of $144 million.

Boating is another favorite pastime — 4 billion boats are owned in the region. Reduced water levels may require dredging to ensure access to the 1,883 marinas, at a total annual cost of $68 million.

Southeast

With warmer weather and warmer water in the Atlantic and the Gulf of Mexico, the region may experience an increased frequency and intensity of storms, sea level rise, and the loss of important agricultural areas, crops and timber species. In addition to coastal infrastructure, forests, agriculture and fisheries, water quality and energy may be subject to notable change and damages as well. Although the picture is incomplete because of data limitations, a valuable glimpse of the extent to which climate change will affect these economic sectors can be gleaned from the summary below.

Coastal Infrastructure

Since 1980, the United States has witnessed 70 natural disasters — including hurricanes, floods, heat waves, and droughts – each causing over $1 billion in damages. Fifty-eight of these events have occurred since 1990 and 29 have been in the Southeast.

Each state except Kentucky experienced at least 16 natural disasters; Texas, Alabama, Georgia, Florida, and North Carolina each experienced at least 21 from 1980-2006.

In 2005, the nation was made painfully aware of the damages possible from extreme storm events when Hurricanes Katrina and Rita struck. A total of 90,000 square miles was declared a federal disaster area following Hurricane Katrina, covering four states and 23 coastal counties and parishes. Eighty percent of the City of New Orleans was flooded, and more than 1,700 lives were lost. More than 350,000 homes were destroyed and another 146,000 seriously damaged. A total of 850,791 housing units were damaged. At an estimated $100,000 repair cost per unit, the total cost to rebuild could exceed $85 billion. In addition to the urban infrastructure damaged by the storms, it was estimated that 2,100 oil platforms and over 15,000 miles of pipeline were damaged. Lost revenue due to the damages amounted to almost $11 billion — 153 million barrels of oil (of an annual total of 547 million) at approximately $70 per barrel at the time of the hurricanes. The questions of what to rebuild, when, and at what cost have spurred debates locally, regionally and nationally, and have stirred deep-seated environmental justice concerns.

Other impacts

Forestry is a major economic sector in the Southeast. For example, the state of South Carolina boasts 60% forest cover and forestry is, after tourism, the second largest economic sector. Given the diversity of species and environmental conditions, short- to medium-term impacts on forests are uncertain. Sea level rise resulting in salt water intrusion may damage forests, particularly in southern Florida and Louisiana. Higher temperatures, decreased soil moisture, and more frequent fires may stress forest ecosystems and ultimately lead to a conversion from forest to savannah and grassland. However, some species may see, at least temporarily, increases in productivity and forested acreage due to a longer growing season, CO2 fertilization, and a switch from stressed to more acclimatized species.

As increased storm frequency and intensity impacts coastal infrastructure, they may also reduce water quality and harm fish populations. Fish and shellfish are at risk in warmer waters and when exposed to increased pollution following major storm events. Much of this pollution will come from stronger storms stressing water management systems and causing sewer systems to overflow, as well as increased nutrient runoff from agricultural lands.

Energy demand will also change in the Southeast as temperatures increase. Increased energy demand to meet cooling needs may stress the energy supply system and waste heat may exacerbate urban heat island effects and their associated human and environmental health impacts.

Northeast and Mid-Atlantic

The Northeast and Mid-Atlantic’s extensive coastal infrastructure — including transportation and energy supply networks and coastal developments — will likely endure the greatest portion of total economic impacts of climate change in the region. Although the picture is incomplete because of data limitations, a valuable glimpse of the extent to which climate change will affect these economic sectors can be gleaned from the summary below.

Coastal Infrastructure

The total value of insured properties vulnerable to hurricanes was nearly $4 trillion in 2004. A Category 4 hurricane touching down in a major metropolitan area would cost $50-66 billion in insurance losses alone.

Sea-level rise of 20 inches (which is expected to happen by 2100) would cause anywhere from $8-$58 billion.

Transportation infrastructure in the region is especially vulnerable to storm surges. In the New York metropolitan area alone, there are 48 major transit facilities at 10 feet or less above sea level — including all the city’s airports. Damage to this transit infrastructure caused by the September 11th attacks amounted to over $7 billion. Similarly, flooding of the Boston subway system in 1996 inflicted over $92 million in damages. Approximately 7,439 miles of urban roads are potentially at risk. Constructing sea wall and bulkhead protection for just 25% of the length of the region’s coastline would cost from roughly $300 million to just under $8 billion. Constructing dikes or levees to protect against a one-meter rise in sea level would run from $300 million to just over $1.5 billion for a quarter of the coastline.

Evacuation effort estimates for the Northeastern coastal region ranges from nearly $2 billion to over $6.5 billion.

Other impacts

Changes in water quality and water temperature on the coasts may negatively affect the $63 billion ocean economy sector, which employs 1.1 million people.

A decrease of 10-20% in skiing days will result in a loss of $405-$810 million per year. Other tourism industries, such as snowmobiling and beach-related sectors, which are primarily located in the vulnerable coastal communities, are likely to experience declines, as well.

The forest industry will likely face declines in productivity as high as 17%. Maple syrup production may also suffer: sap flow is predicted to fall by 17-39%, inflicting a loss of $5.3-$12.1 million in annual revenue to this $31 million industry.

Effects on agricultural crops are expected to be mixed — at least for the short- to medium term — causing losses for some crops and gains for others. Losses are expected to be significant; New York’s agricultural yield may be reduced by as much as 40%, causing $1.2 billion in annual damages. Threat of drought is expected to rise, affecting the agricultural sector. For example, a 1999 nation-wide drought cost the Northeast region around $973 million in net farm-income losses

Alaska

The majority of Alaska’s population resides along the southern coast, including Anchorage, the largest city and the only one with a population greater than 100,000. Unlike the arctic interior of the state, these coastal regions (and almost 34,000 total miles of tidal shoreline including the islands) are vulnerable to sea level rise and storms. Although the picture is incomplete because of data limitations, a valuable glimpse of the extent to which climate change will affect these economic sectors can be gleaned from the summary below.

Public Infrastructure

In total, climate change is expected to add $5-10 billion to an already $32-56 billion infrastructure maintenance budget through 2080 for the state.

The 800-mile, 48-inch diameter warm oil Trans-Alaska Pipeline crosses nearly the entire state. The pipeline cost approximately $8 billion to construct, and approximately $800 million of those construction costs were due to the need to elevate the pipeline above permafrost over half its length. Since its construction, the thawing of permafrost has reduced structural integrity, which leads to spills.

Significant impacts are predicted for human settlements, particularly coastal towns and villages vulnerable to sea level rise and more frequent and intense storms. Cost estimates of shoreline protection and village relocation continue to rise. The most recent estimates by the US Army Corps of Engineers are up to $450 million in relocation costs for Shismaref, Kivalina and the village of Newtok. Other

Forests are expected to be negatively affected by climate change. Short-term vulnerabilities pose significant costs resulting from thawing permafrost and unstable soils, increased fire and insect outbreaks. Increased occurrence of fire and pest outbreaks put both natural and managed forests at risk. In 1992, the largest documented bark beetle outbreak in North America damaged over 2.3 million acres on Kenai Peninsula. Additional insect outbreaks in the 1990s damaged over 800,000 acres of forest. If an outbreak of this scale were to hit the state’s commercial forests, upwards of 50% of the harvestable land area could be lost, causing an $332 million loss to the industry.

Forest fires have also been increasing in recent history, their intensity associated with warm and dry periods in the climatic record. As of 1970, approximately 2.5 million acres burned each year. This number jumped to 7 million acres per year by the 1990s. In 1996, a 37,000 acre forest and peat fire caused $96 million in direct losses and destroyed 450 structures, including 200 homes. Based on a median housing value of about $200,000 today, damage of this magnitude would cost nearly $40 million.

The total value of fisheries in Alaska is approximately $2.8 billion and employs over 20,000 workers. Changes in ocean temperatures, expected to be slower than temperatures over land, may affect spawning and migratory behaviors of many commercially valuable species. Sea level rise may impact harbor infrastructure, requiring retrofits and upgrades to docks. Higher temperatures may increase cooling needs for storage and processing of catch. All of these impacts are likely to add cost to an already vulnerable industry and will likely negatively impact the state economy.

Hawaii and US Affiliated Islands

Over the past century, average temperatures have increased 1ºF (0.6ºC) in the Caribbean and 0.4ºF (0.2ºC) in the Pacific. Global average sea level has risen 4-8 inches over the last century, though with significant local variation. The rate of sea level rise in the Gulf of Mexico is presently 3.9 inches per century. Coastal infrastructure will be most affected by continued climate change patterns. Although the picture is incomplete because of data limitations, a valuable glimpse of the extent to which climate change will affect these economic sectors can be gleaned from the summary below.

Coastal Infrastructure

|

The U.S. Economic Impacts of Climate Change and the Costs of Inaction.

|

Climate change will likely stress already deficient infrastructure on the islands. According to the American Society of Civil Engineers, 47% of Hawaii’s bridges are already structurally deficient or functionally obsolete. The state also has 77 high hazard dams, whose failure would lead to loss of life and property damage. Repairs (not including those needed due to effects of climate change) to Hawaii’s drinking water infrastructure could exceed $146 million over the next 20 years; its wastewater infrastructure, $1.74 billion. The biggest threats to this already burdened infrastructure will be sea level rise and tropical storms.

Increased incidence of extreme weather events will continue to stress the islands. There have been a number of destructive hurricanes to hit the US islands in recent

years. Hurricane Marilyn caused as much as $4 billion in damages in the US Virgin Islands. Hurricane damages

in Hawaii from 1957-1995 topped $2.7 billion. Hurricane

Iniki, the most powerful hurricane (Category 4) to hit Hawaii, caused 7 deaths, $2 billion in damages, and $295 million in FEMA disaster relief in 1992.

Hurricane Georges hit Puerto Rico in 1998, bringing 26 inches of rain in 24 hours that caused major flooding, landslides, infrastructure and agricultural damages, and left 12 people dead. Puerto Rico lost 75% of its water and sewer infrastructure. Ninety-six percent of its electrical power network, 50% of its utility poles and cables, and 33,100 homes were damaged or destroyed. Road damages exceeded $25 million, and damage to public schools was about $23-29 million. Its agricultural areas were also affected; 75% of the coffee crop, 95% of the plantain and banana crops, and 65% of all poultry production were temporarily lost. In total, Hurricane Georges cost Puerto Rico $2.3 billion in damages; damages to the US mainland damages totaled $6.9 billion.

With storms and sea level rise come beach erosion, which occurs 150 times faster than the rate of sea level rise. Some Caribbean islands are already losing 9 feet of coastline each decade due to erosion and the projected rate of sea level rise would erode more than 33 feet of coastline per decade in the foreseeable future.

Other

Climate impacts on coastal infrastructure; particularly roads, bridges, docks, water supply systems and hotels, will make tourism on the islands less attractive — as will impacts on local tropical forests and coral reefs. Changes in temperature and precipitation may further make some locations unattractive to visitors.

The U.S. Economic Impacts of Climate Change and the Costs of Inaction