Experts forecast large decline in Arctic sea ice

Experts forecast large decline in Arctic sea ice

mongabay.com

September 7, 2007

|

|

Summer sea ice off Alaska’s north coast will likely shrink to nearly half the area it covered in the 1980s by 2050, report scientists from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. The loss of ice would have a significant impact on mammals dependent on sea ice, including polar bear and walrus.

Oceanographer James Overland of NOAA’s Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory in Seattle and meteorologist Muyin Wang of NOAA’s Joint Institute for the Study of the Atmosphere and Ocean at the University of Washington in Seattle compared 20 computer models from the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) with observations from 1979 through 1999. They found that during the 1980s sea ice receded 30 to 50 miles each summer off the north coast of Alaska, but that the area could reach 300 to 500 miles by 2050.

“We wanted to assess how much confidence we can have in regional projections of sea ice from the 20 computer models used in the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Fourth Assessment Report,” said Overland. “Our purpose was to first ensure that our models could replicate observations of the baseline conditions during the 1979-1999 period before considering 21st century projections. Our results present a consistent picture: there is a substantial loss of sea ice for most models by 2050.”

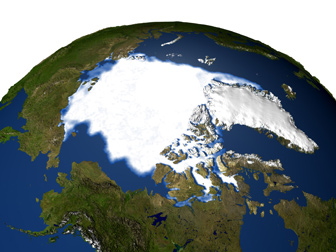

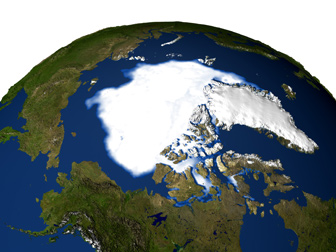

Sea ice minimum 1979  Sea ice minimum 2005. Courtesy of NASA |

The new study, published in Geophysical Research Letters, follows research published earlier this year in the same journal. That study, conducted by Julienne Stroeve of the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC) and his colleagues, showed that September sea ice extent retreated at a rate of about 7.8 percent per decade during the 1953-2006 period, not the 2.5 percent projected by simulations. The basis for the data–a combination of satellite measurements and early aircraft and ship reports–is considered more reliable than the earlier records.

The Arctic is particularly sensitive to changes in the extent of sea ice, which helps reflect sunlight back into space, cooling the region. When sea ice melts, the dark areas of open water absorb the sun’s radiation, trigger a positive feedback loop that worsens melting.

Melting sea ice has implications for polar bears, which are currently being considered for protection under the Endangered Species Act. A November 2006 study published by scientists from the U.S. Geological Survey and the Canadian Wildlife Service, found a 22 percent decline in the size of the western Hudson Bay polar bear population between 1987 and 2004. The research also found that only 43 percent of polar bear cubs in the surveyed area survived their first year, compared to a 65 percent survival rate in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Meanwhile in September, Ian Stirling, a research scientist with the Canadian Wildlife Service, reported that the average weight of adult female polar bears in western Hudson Bay have fallen from 650 pounds in 1980 to just 507 pounds in 2004.

Other reports indicate that drowned polar bears are being found for the first time in Alaska. Researchers speculate that greater distances between ice sheets could be taking a toll on the bears. While bears are capable of swimming long distances–up to 60 miles (100 km) without stopping–it is conceivable that they could suffer from exhaustion during an unexpectedly arduous swim. A shorter spring hunting season caused by progressively earlier breakup of sea ice, reduces the chances of reproductive success for female polar bears.

The loss of ice also makes it more difficult for bears to find food. Unlike grizzly bears, polar bears aren’t adapted to hunting land animals like caribou, instead feeding primarily on seals.