Stopping malaria using smell

Stopping malaria using smell

Vanderbilt University

August 31, 2007

Researchers have taken an important first step in developing improved repellants to protect mankind from its deadliest insect parasite: the mosquito

|

|

By mapping a specialized sensory organ that the malaria mosquito uses to zero in on its human prey, an international team of researchers has taken an important step toward developing new and improved repellants and attractants that can be used to reduce the threat of malaria, generally considered the most prevalent life-threatening disease in the world.

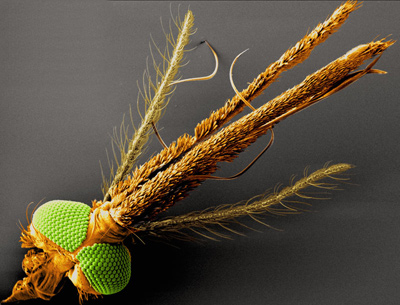

The sensory organ is the maxillary palp. It is one of three structures extending from the mosquito’s head that together provide it with its sense of smell and taste. The other two are the feathery antennae that serve as general-purpose olfactory organs and respond to a wide range of different chemicals and the proboscis that contains sensors designed for close-in odor and taste detection.

The detailed map of the maxillary palp, which was published online in the journal Current Biology on Aug. 30, has determined that it contains a unique array of highly specialized receptor cells that detect carbon dioxide and octenol, key chemical signals that the insects use to find human prey.

“These receptors are highly sensitive, which suggests that the maxillary palps may serve as the malaria mosquito’s long-range detection system,” says Tan Lu, a graduate student at Vanderbilt who is the paper’s first author.

“We haven’t proven it yet, but the implication is that if you took away the maxillary palp the mosquito would not do nearly as well at finding human prey,” adds Laurence J. Zwiebel, professor of biological sciences at Vanderbilt, who headed the study.

The research was performed by collaborators from Vanderbilt, Yale and Wageningen University in the Netherlands. They are part of a team that also includes researchers from the Ifakara Health Research and Development Centre in Tanzania and the Medical Research Council Laboratories in the Gambia that is funded by a grant from the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health through the Grand Challenges to Global Health Initiative in 2005 to develop a chemical strategy to combat the spread of malaria by the Anopheles mosquito.

“This paper marks a threshold in our grand challenge project because it provides a biological context and then strips it down to a few molecular targets that we are using to develop chemical modifiers that should have direct impacts on the mosquito’s behavior,” says Zwiebel.

The study fills a major gap in the scientific understanding of the malaria mosquito’s olfactory system. Although considerable research has been done on the physiology and molecular biology of Anopheles gambiae’s antennae and proboscis, there have been few studies of its maxillary palps. Most of the previous work that had been done on this “accessory olfactory appendage” was performed in another species of mosquito, Aedes aeqypti, the carrier of dengue and yellow fever.

Previous work found that the maxillary palps of the A. aeqypti were sensitive to carbon dioxide and octenol. So the discovery that this was also the case in An. gambiae did not come as a big surprise. However, the researchers found that the malaria mosquito uses different sets of receptors for this purpose which help explain why it appears to rely less on carbon dioxide and more on human-specific chemical compounds in seeking out hosts than does A. aegypti.

The mosquito’s elaborate “nose” consists of hundreds of hollow hair-like structures called sensilla attached to its antennae, maxillary palps and proboscis. The tips of these structures are perforated with thousands of tiny holes that let aromatic compounds penetrate to their interior, where they encounter thread-like extensions from neurons which are tuned to detect specific molecules.

Compared to the mosquito’s antennae, which are designed to detect hundreds of different compounds, the study found that the maxillary palps are highly specialized. “The amazing thing that we found was that all the sensory hairs that line the bottom of the maxillary palps are identical,” says Zwiebel. They are all attached to three neurons: one which is tuned to detect carbon dioxide; one which is tuned to detect octenol; and one which serves to enhance general olfactory reception.

In addition to Zwiebel and Lu, the Vanderbilt researchers who contributed to the study are Quirong Wang, Michael Rutzler, Hyung-Wook Kwon and R. Jason Pitts. The Wageningen team consists of Yu Tong Qiu, Joop J.A. van Loon and Willem Takken. The Yale contributors are Jae Young Kwon and John R. Carlson.

The research was funded by a Gates Foundation Grand Challenges in Global Health Initiative grant and by grants from the National Institutes of Health.