NGOs should use palm oil to drive conservation

NGOs should use palm oil to drive conservation

Rhett A. Butler, mongabay.com

August 29, 2007

|

|

Environmentalists view the expansion of oil palm plantations in southeast Asia as one of the greatest threats to the region’s forests and biodiversity. Campaigners say oil palm is driving the conversion of tens of thousands of hectares of peatlands and lowland forest in Indonesia and Malaysia, putting wildlife at risk, increasing the vulnerability of the forests to fires, and triggering large emissions of greenhouse gases. Pressure from these groups have in recent months convinced European policymakers to reconsider sourcing energy crop production to the region.

Palm oil producers are fighting back, accusing the West of hypocrisy for criticizing their production while overlooking environmental harm caused by biofuel production in other parts of the world, including Amazonia (soy biodiesel and sugar cane ethanol), Europe (rapeseed), and the United States (corn ethanol).

Now a new paper calls for a truce, proposing that conservationists work with palm oil producers to protect particularly important areas of biodiversity.

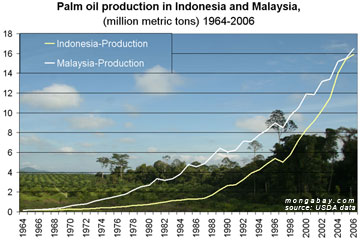

Chart showing annual palm oil production by Malaysia and Indonesia from 1964-2006. Click to enlarge. |

Writing in Nature, Lian Pin Koh and David S. Wilcove from Princeton University, argue that the high yield and high prices that make oil palm so attractive “could be turned to a biodiversity advantage.” They suggest that green groups could buy small tracts of existing oil palm plantations and use the revenue they generate to acquire land to establish a network of privately-owned nature reserves for biodiversity conservation.

“A typical mature oil-palm plantation in Sabah, Malaysia, generates an annual net profit of roughly $2,000 per hectare,” write the authors. “Based on the current price of $12,500 per hectare for oil palm-cultivated land, the capital investment could be recovered in just 6 years. After this initial period, a 5,000-hectare oil palm plantation could generate annual profits amounting to some $10 million, which could be used to acquire 1,800 hectares of forested land annually to be set aside as private nature reserves.”

Koh and Wilcove say the scheme would require collaboration between “large conservation donor groups to fund the initial investments and with local oil-palm companies

for their expertise in running the plantations,” but that the relationship could be a “win-win partnership… because NGOs would be able to protect forests using the oil palm revenue and the companies would be able to enhance their corporate image to satisfy environmentally-conscious consumers.”

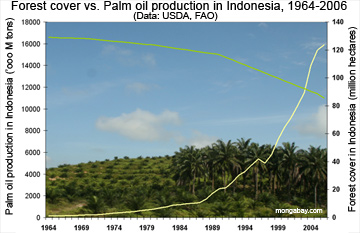

Forest cover versus palm oil production in Indonesia. |

“We think NGOs can participate in such joint ventures without losing their integrity if they go into it with the appropriate level of caution. Afterall, there have been many examples of successful collaborations between environmental groups and industry leaders in the USA and elsewhere,” Koh told mongabay.com via email. “Having said that, we certainly do not want all of the NGOs to embrace our idea, because we feel that some should remain well outside the partnership, serving as much-needed critical voices to pressure governments and oil palm companies to avoid further losses of pristine habitats.”

Koh and Wilcove believe that the development of a premium market could help entice producers into working with conservationists.

“Because such oil-palm plantations would be motivated mainly by conservation objectives, they could provide the industry with leadership for the sustainable production of palm oil through environmentally-friendly management practices,” they write. “This could also drive the development of a premium market for sustainable oil-palm products and thereby generate economic incentives for more palm-oil producers to adopt sustainable practices.”

Koh and Wilcove appear to be optimistic that this price premium, as well as the “green” marketing benefits, can overcome the inherent conflict of interest between the two groups. After all, why would producers want to help set up direct competitors and fund opposition to oil palm expansion unless they were sure to get something tangible in return?

CITATION: Lian Pin Koh and David S. Wilcove (2007). Cashing in palm oil for conservation. Nature Vol 448|30 August 2007

Related articles

Can cattle ranchers and soy farmers save the Amazon?

(6/7/2007) John Cain Carter, a Texas rancher who moved to the the Brazilian state of Mato Grosso 11 years ago and founded what is perhaps the most innovative organization working in the Amazon, Aliança da Terra, believes the only way to save the Amazon is through the market. Carter says that by giving producers incentives to reduce their impact on the forest, the market can succeed where conservation efforts have failed. What is most remarkable about Aliança’s system is that it has the potential to be applied to any commodity anywhere in the world. That means palm oil in Borneo could be certified just as easily as sugar cane in Brazil or sheep in New Zealand. By addressing the supply chain, tracing agricultural products back to the specific fields where they were produced, the system offers perhaps the best market-based solution to combating deforestation. Combining these approaches with large-scale land conservation and scientific research offers what may be the best hope for saving the Amazon.

Palm oil doesn’t have to be bad for the environment

(4/4/2007) As traditionally practiced in southeast Asia, oil palm cultivation is responsible for widespread deforestation that reduces biodiversity, degrades important ecological services, worsens climate change, and traps workers in inequitable conditions sometimes analogous to slavery. This doesn’t have to be the case. Following examples set forth by the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil and firms like Golden Hope Plantations Berhad, a Malaysian palm oil producer, oil palm can be cultivated in a manner that helps mitigate climate change, preserves biodiversity, and brings economic opportunities to desperately poor rural populations.

Eco-friendly palm oil could help alleviate poverty in Indonesia

(4/3/2007) The Associated Press (AP) recently quoted Marcel Silvius, a climate expert at Wetlands International in the Netherlands, as saying palm oil is a failure as a biofuel. This would be a misleading statement and one that doesn’t help efforts to devise a workable solution to the multiplicity of issues surrounding the use of palm oil.

|

Environmental concerns mount as palm oil production grows

(5/15/2007) The booming market for palm oil is driving record production but fueling rising concerns over the environmental impact of the supposedly “green” bioenergy source. The two leading producers of palm oil, Malaysia and Indonesia, have rapidly expanded palm oil production in recent years, often at the expense of biodiverse rainforests and carbon-rich peatlands that store billions of tons of greenhouse gases. Environmentalists say that due to these factors, burning of palm oil can at times be more damaging the global climate than the use of fossil fuels.

How private equity can profit from carbon offsets in Indonesia

(8/29/2007) The emerging carbon market for avoided deforestation presents unprecedented opportunities for private equity to make profitable investments that also help protect the environment. Indeed, for the first time, conservation may be associated with positive financial returns. Here’s a brief look at how private equity and other investors can capitalize on this opportunity to earn attractive returns while fighting climate change, protecting ecosystem services, and safeguarding endangered species like orangutans.

Could peatlands conservation be more profitable than palm oil?

(8/22/2007) This past June, World Bank published a report warning that climate change presents serious risks to Indonesia, including the possibility of losing 2,000 islands as sea levels rise. While this scenario is dire, proposed mechanisms for addressing climate change, notably carbon credits through avoided deforestation, offer a unique opportunity for Indonesia to strengthen its economy while demonstrating worldwide innovative political and environmental leadership. In a July 29th editorial we argued that in some cases, preserving ecosystems for carbon credits could be more valuable than conversion for oil palm plantations, providing higher tax revenue for the Indonesian treasury while at the same time offering attractive economic returns for investors.

Why is palm oil replacing tropical rainforests?

(4/25/2006) In a word, economics, though deeper analysis of a proposal in Indonesia suggests that oil palm development might be a cover for something more lucrative: logging. Recently much has been made about the conversion of Asia’s biodiverse rainforests for oil-palm cultivation. Environmental organizations have warned that by eating foods that use palm oil as an ingredient, Western consumers are directly fueling the destruction of orangutan habitat and sensitive ecosystems. So, why is it that oil-palm plantations now cover millions of hectares across Malaysia, Indonesia, and Thailand? Why has oil palm become the world’s number one fruit crop, trouncing its nearest competitor, the humble banana? The answer lies in the crop’s unparalleled productivity. Simply put, oil palm is the most productive oil seed in the world. A single hectare of oil palm may yield 5,000 kilograms of crude oil, or nearly 6,000 liters of crude.