Economics of next generation biofuels

Economics of next generation biofuels

John Wiley & Sons

August 8, 2007

Production costs of advanced biofuels is similar to grain-ethanol

Second generation’ biorefineries — those making biofuel from lignocellulosic feedstocks like straw, grasses and wood — have long been touted as the successor to today’s grain ethanol plants, but until now the technology has been considered too expensive to compete. However, recent increases in grain prices mean that production costs are now similar for grain ethanol and second generation biofuels, according to a paper published in the first edition of Biofuels, Bioproducts & Biorefining.

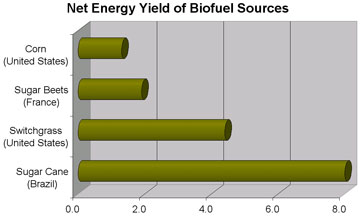

The switch to second generation biofuels will reduce competition with grain for food and feed, and allow the utilization of materials like straw which would otherwise go to waste. The biorefineries will also be able to use lignocellulosic crops like poplar and switchgrass, which can be grown on land less suitable for farming than traditional row crops. These findings should be a boost to companies hoping to establish themselves in this emerging field.

Two researchers working at the Department of Mechanical Engineering at Iowa State University set out to compare the capital and operating costs of generating fuel from starch and cellulose-containing materials.

Chart showing Net Energy Yield from various fuel crops.

|

They showed that the capital costs for 150 million gallon gasoline equivalent capacity range from around $111 million for a conventional grain ethanol plant to $854 million for an advanced (Fischer Tropsch) plant. The difference in the final cost of the fuel, however, was less severe, being $1.74 for grain ethanol when corn costs $3.00 per bushel and $1.80 for cellulosic biofuel when biomass costs $50 per ton.

The authors compared biochemical and thermochemical approaches to biofuels. They showed that both have much higher capital costs than conventional grain ethanol plants, but that neither had a significant cost advantage over the other.

Comparing the costs of biofuels is complicated by the fact that most studies rarely employ the same bases for economic evaluations. Differences in assumed plant size, biomass costs, method of project financing, and even the year in which the analyses are performed can skew comparisons.

“Although the costs of production are comparable for grain ethanol and cellulosic biofuels, the much higher capital costs of the cellulosic plants will be an impediment to their commercialization,” says ISU graduate student Mark Wright, one of the paper’s authors.

Wright M and Brown R; Comparative economics of biorefineries based on the biochemical and thermo-chemical platforms; Biofuels, Bioprod. Bioref. 1:49-56 (2007); DOI: 10.1002/bbb.8

Related articles

Corn ethanol is not the solution to energy independence

(7/18/2007) A new report claims that corn ethanol will not significantly offset U.S. fossil fuel consumption without “unacceptable” environmental and economic consequences.

Miscanthus bests switchgrass as biofuel source

(7/11/2007) In a side-by-side comparison, miscanthus (Miscanthus x giganteus) grass has been shown to be a more productive bioenergy source than switchgrass (Panicum virgatum), according to research presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Plant Biologists in Chicago.

$100 billion invested in renewable energy in 2006

(6/20/2007) $100 billion poured into renewable energy and energy efficiency in 2006, a 25 percent jump from 2005, reports a new analysis by the UN Environment Programme (UNEP).

Biofuels demand will increase, not decrease, world food supplies

(3/27/2007) As concerns mount over fuel-versus-food competition for crops, a Michigan State University ethanol expert says that cellulosic ethanol could render the debate moot. Bruce Dale, an MSU chemical engineering and materials science professor, notes that ethanol can be made from cellulosic materials, like farm waste, instead of corn grain.

New green biofuels process could meet all U.S. transportation needs

(3/14/2007) Purdue University chemical engineers have proposed a new environmentally friendly process for producing liquid fuels from plant matter – or biomass – potentially available from agricultural and forest waste, providing all of the fuel needed for “the entire U.S. transportation sector.”

Government pledges $385M for cellulosic ethanol

(3/8/2007) The U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) announced it will invest up to $385 million over the next four years for six biorefinery projects capable of producing more than 130 million gallons of cellulosic ethanol annually.

High oil prices fuel bioenergy push

(5/9/2006) High oil prices and growing concerns over climate change are driving investment and innovation in the biofuels sector as countries and industry increasingly look towards renewable bioenergy to replace fossil fuels. Bill Gates, the world’s richest man, has recently invested $84 million in an American ethanol company while global energy gluttons ranging from the United States to China are setting long-term targets for the switch to such fuels which potentially offer a secure domestic source of renewable energy and fewer environmental headaches. Biofuels are fuels that are derived from biomass, including recently living organisms like plants or their metabolic byproducts like cow manure. Unlike fossil fuels — like coal, petroleum, and natural gas, which are finite resources — biofuels are a renewable source of energy that can be replenished on an ongoing basis. In general, biofuels are biodegradable and, when burned, have fewer emissions than traditional hydrocarbon-based fuels. Typically, biofuels are blended with traditional petroleum-based fuels, though it is possible to run existing diesel, engines purely on biodiesel, something which holds a great deal of promise as an alternative energy source to replace fossil fuels. Further, because biofuels are generally derived from plants which absorb carbon from the atmosphere as they grow, biofuel production offers the potential to help offset carbon dioxide emissions and mitigate climate change.