Coral reefs declining faster than rainforests

Coral cover declines by 50% since 1980

Coral reefs declining faster than rainforests

mongabay.com

August 8, 2007

Coral reefs in the Pacific Ocean are dying faster than previously thought due to costal development, climate change, and disease, reports a study published Wednesday in the online journal PLoS One. Nearly 600 square miles of reef have disappeared per year since the late 1960s, a rate twice that of tropical rainforest loss.

Compiling and analyzing a database of 6,000 quantitative surveys performed between 1968 and 2004 of more than 2,600 Indo-Pacific coral reefs, John Bruno and Elizabeth Selig of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC) found that reefs are disappearing at a rate of one percent per year. Coral cover fell from 40 percent in the early 1980s to around 20 percent by 2003. Historically coral cover is around 50 percent. Only about 2 percent of Indo-Pacific reefs meet this threshold, considered a measure of reef health.

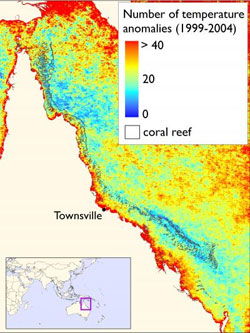

The number of weeks that ocean temperature exceeded its long-term weekly average by more than one degree Celsius between 1999 and 2004. Anomalously warm conditions like these can cause outbreaks of the coral disease white syndrome, contributing to reef decline. Credit: Elizabeth Selig |

“We have already lost half of the world’s reef-building corals,” said Bruno, lead author of the study.

The researchers were surprised to find that coral cover declined in both protected and unprotected reefs, a sign that coral loss is “a global phenomenon, likely due in part to large-scale stressors such as climate change,” according to UNC.

“We can do a far better job of developing technologies and implementing smart policies that will offset climate change,” Bruno said. “We can also work on mitigating the effects of other stressors to corals including nutrient pollution and destructive fishing practices.”

Coral reefs play a critical economic role in many Indo-Pacific communities, offering protection from coastal erosion and supporting marine fisheries and tourism.

“Indo-Pacific reefs have played an important economic and cultural role in the region for hundreds of years and their continued decline could mean the loss of millions of dollars in fisheries and tourism,” said Selig. “It’s like when everything in the forest is gone except for little twigs, a few lone trees.”

A reefscape from the Great Barrier Reef. Credit: AIMS Long Term Monitoring Program |

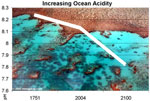

Scientists have expressed a great deal of concern over the potential impact of climate change on coral reef ecosystems. Both increasingly levels of acidity, which reduce the ability of coral to generate their main structural material, and higher sea temperatures, which can cause “bleaching” or expulsion of the symbiotic algae that enable corals to feed, are cited as the primary risks to reefs in a world of higher atmospheric carbon dioxide levels. Some research suggests that as much as 95 percent of the corals on Australia’s Great Barrier Reef could die by 2050 should temperatures rise by 2 ocean temperatures increase by the 1.5 degrees Celsius projected by climate scientists. Despite the bleak outlook, it appears that some corals may be able to adjust to changing conditions. The end result is that reefs 50 years from now may be quite different than reefs of the present.

Related articles

Coral diseases largely result from human activities

(5/17/2007) The apparent increase in infectious disease among coral is likely the result of environmental change and, as such, researchers should focus on understanding the relationship between coral diseases and environmental changes, rather than the diseases themselves, argues a paper published in the August 2007 issue of the Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology.

|

Global warming is killing coral reefs

(5/7/2007) A new study provides further evidence that climate change is adversely affecting coral reefs. While previous studies have linked higher ocean temperatures to coral bleaching events, the new research, published in PLoS Biology, found that climate change may increasing the incidence of disease in Great Barrier Reef corals. Omniously, the research also shows that healthy reefs, with the highest density of corals, are hit the hardest by disease.

|

Some corals may survive acidification caused by rising CO2 levels

(3/29/2007) Several studies have shown that increased atmospheric carbon dioxide levels are acidifying the world’s oceans. This is significant for coral reefs because acidification strips carbonate ions from seawater, making it more difficult for corals to build the calcium carbonate skeletons that serve as their structural basis. Research has shown that many species of coral, as well as other marine microorganisms, fare quite poorly under the increasingly acidic conditions forecast by some models. However, the news may not be bad for all types of corals. A study published in the March 30 issue of the journal Science, suggests that some corals may weather acidification better than others.

|

Carbon dioxide levels threaten oceans regardless of global warming

(3/8/2007) Rising levels of carbon dioxide will have wide-ranging impacts on the world’s oceans regardless of climate change, reports a study published in the March 9, 2007, issue of the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

Increasingly acidic oceans damaging to marine life

(7/5/2006) Carbon dioxide emissions are altering ocean chemistry and putting sea life at risk according to a new report released today. The report, “Impacts of Ocean Acidification on Coral Reefs and Other Marine Calcifiers,” summarizes known effects of increased atmospheric carbon dioxide on marine organisms that produce calcium carbonate skeletal structures, such as corals. Oceans worldwide absorbed approximately 118 billion metric tons of carbon between 1800 and 1994 according to the report, resulting in increased ocean acidity, which reduces the availability of carbonate ions needed for the production of calcium carbonate structures.

This article is based on a news release from UNC