Pro-poor conservation

Pro-poor conservation

mongabay.com

July 1, 2007

A new paper challenges conservationists to focus on improving the livelihoods of rural poor

Biodiversity conservation is often associated with the protection of charismatic animals and beautiful landscapes. Missing is consideration of the role that biodiversity plays in the livelihoods of hundreds of millions of people around the world, who rely on hunting, plant collection, and other services afforded by biodiversity for everyday subsistence.

A new paper examines this discrepancy and proposes strategies to ensure that conservation strategies can better provide for the needs of populations that are most dependent on its services.

Writing in Biotropica, David Kaimowitz and Douglas Sheil of the Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR) in Jakarta, Indonesia, argue that conservation requires a careful balance between preserving species from going extinct and meeting the human needs of some of the world’s poorest populations.

“For hundreds of millions of people, biodiversity is about eating, staying healthy, and finding shelter. Meeting these people’s basic needs should receive greater priority in the conservation agenda,” they write. “Pro-poor conservation’—that is, conservation that aims to support poor people— explicitly seeks to address basic human needs. Such an emphasis has many potential synergies with more conventional conservation goals.”

The Masai are a warrior tribe in Kenya whose livelihood is dependent on cattle herding, an activity that has sometimes put them at odds with conservationists who have forced them from their traditional lands. |

They note that while conservation NGOs have developed some strategies to generating income for poor people through ecotourism and the sale of natural products, too little effort has been devoted to maintaining “wild and semiwild species and habitats specifically to fulfill human needs,” including plants and animals used for crops and as sources of medicinal products.

“For several billion people, wild plants and animals are not just objects of admiration, but the essential elements of daily life.While most of these people grow crops and raise animals, they still depend to a surprising degree on wild resources obtained through hunting, gathering, and fishing,” wrote Kaimowitz and Sheil. “Ethnographic studies typically find these people use hundreds of species for a wide range of purposes.Wild meat, fish, and insects provide much of their protein, while forest fruits and vegetables are a source of vitamins.

The authors note that wild meat and protein are the source of more than 20 percent of all protein in 62 developing countries while it is not unusual for wild plants and animals to account for 20-30 percent of rural peoples’ income in developing countries.

Despite this importance, these resources are increasingly threatened by overexploitation and environmental degradation–especially deforestation. and pollution. At times, even well-intentioned conservation efforts can worsen their plight by restricting access to key plants and animals and further impoverishing the rural poor.

So what’s the solution?

Kaimowitz and Sheil say the basic principles of pro-poor conservation include “finding, developing, maintaining, and safeguarding managed landscapes that include adequate areas to serve as sources of fauna and flora for local people, especially those who are vulnerable and marginalized.” This entails focusing on areas where “many people rely on declining wild resources with few substitutes” — often drier places which are more heavily disturbed and have fewer charismatic animal species, like Sub-Saharan Africa and the mountainous areas of Asia and the Pacific. It means allowing the rural poor to make use of buffer zones around strictly protected areas and even establishing special zones specifically for their use. Further, communities should be actively involved in the design, implementation, and enforcement of rules regulating hunting, fishing, and gathering plant material, while limiting outsiders’ access to local resources. Kaimowitz and Sheil write that these efforts may involve “the domestication or more intensive management of traditionally wild plants and animals.”

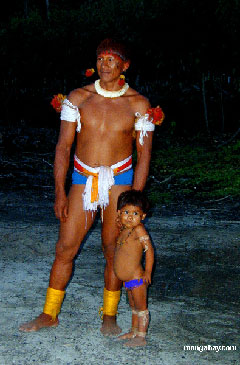

Indigenous use of forest resources is increasingly incorporated into forest conservation schemes in the Amazon. |

“A pro-poor approach to conservation inevitably implies working closely with communities rather than fencing them out. It goes beyond most (though by no means all) previous community,’ participatory,’ or development’ efforts intended primarily to win local acceptance of other people’s conservation agendas,” they write. “It involves focusing on the weak and vulnerable, not only the politically perceptive and influential.”

The authors don’t suggest that pro-poor conservation will conserve everything; some species will require special efforts to preserve them. In these cases, communities may need to be compensated for forfeiting access to resources in order to protect these species.

Nevertheless, say the authors, conservation organizations will need to offer real benefits to local people or “retaining public funding or political support from governments in the tropics will prove increasingly difficult.”

“We are not suggesting that species that do not benefit poor people should be allowed to disappear forever. But we are suggesting that conservation can and should address broader, more diversified, and more democratically defined goals, and should recognize and address the needs and aspirations of local people: especially the poor and vulnerable. Such efforts might allow people to live happier and more productive lives, and could also strengthen local support for conserving species for their own sake,” they write.

“For hundreds of millions of people, biodiversity is about eating, staying healthy, and finding shelter. Such needs, in addition to those of the tiger and other endangered species, must also be considered a conservation priority. Clearly it is not a question of either/or,’ but rather of finding a better balance.”

CITATION: David Kaimowitz and Douglas Sheil (2007). Conserving What and for Whom? Why Conservation Should Help Meet Basic Human Needs in the Tropics. Biotropica 10.1111/j.1744-7429.2007.00332.x

Related

Indigenous people are key to rainforest conservation efforts. October 31, 2006

Integrated biodiversity and cultural conservation can be more effective than traditional protected areas while delivering health benefits to local populations. Tropical rainforests house hundreds of thousands of species of plants, many of which hold promise for their compounds which can be used to ward off pests and fight human disease. No one understands the secrets of these plants better than indigenous shamans -medicine men and women – who have developed boundless knowledge of this library of flora for curing everything from foot rot to diabetes. But like the forests themselves, the knowledge of these botanical wizards is fast-disappearing due to deforestation and profound cultural transformation among younger generations. The combined loss of this knowledge and these forests irreplaceably impoverishes the world of cultural and biological diversity.

Plan to bring lions, elephants to U.S. excludes Africans. May 22, 2007

Writing in the June 2007 Scientific American one of the scientists who helped put forth a radical proposal to reintroduce historical megafauna — including camels, cheetah, elephants, and lions — revisits the scheme, reviewing its basic points and refuting some of the criticism the plan received from the general public and other conservation biologists.