Roughly 80 percent of Sulawesi’s richest forests have been degraded and destroyed for agriculture, logging, and mining, reports a ground-breaking assessment of the Indonesian island’s forests.

Island of unusual biodiversity

Straddling the Wallace line, an area of biological discontinuity between Asia and Australia, Sulawesi is characterized by high levels of endemism–more than 60 percent of its mammals and more than one third of its birds are found nowhere else on the planet. So unusual the island’s biodiversity, it helped inspire Alfred Russel Wallace to independently propose a theory of natural selection that pushed Charles Darwin to publish his masterwork, The Origin of Species before he was ready to go to press. Nevertheless, despite its storied history and species richness, Sulawsi’s biodiversity is poorly known by scientists. More troubling, the island has long been overlooked conservationists.

Their neglect has been costly–Sulawesi’s forests have fast been converted for agriculture, felled by loggers, and degraded by miners. A new study, published in the journal Biotropica reveals the extent of these losses by creating an extensive ecosystem disturbance map of the island.

Assessing the damage

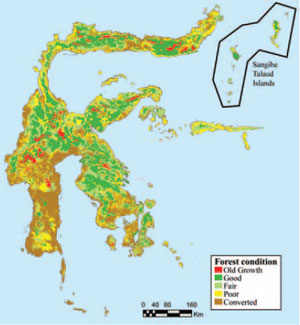

Forest condition on the island of Sulawesi. A composite of 32 Landsat images was manually classified based upon both visual inspection and the results from several remote-sensing techniques. The ‘converted’ class includes all sites that are completely dominated by human activity, including urban areas and regions of intensive agriculture and plantations. Image and caption courtesy of Canon, et. al (2007). |

Using a combination of remote sensing and field surveys, Texas Tech University biologist Dr. Charles H. Cannon and colleagues developed a ranking system to prioritize areas for conservation on the island, based on five criteria: forest canopy condition, forest type and its endangerment, forest status based on its landscape setting, a numerical simulation of forest fate given observed trends, and the overall size of the site. The process showed that Sulawesi’s most accessible and productive ecosystems–its lowland forests and wetlands–are also its rarest. Less than five percent of the island’s mangrove and lowland forests are undisturbed while 99 percent of its wetlands have been damaged of destroyed.

“The top two endangered forest types were alluvial sites below 850 m elevation while lowland forest on limestone ranked third,” the authors write. “These patterns closely follow soil fertility and

site accessibility trends, with lowland alluvium converting easily into productive agricultural land while marginal upland forests on poor soils are avoided. The heavily populated southwestern arm is almost entirely converted into intensive agriculture and urban areas.”

Overall more than half of Sulawesi’s forests were in poor condition or had been converted for intensive human use. Only 30 percent of its forests–most of these in upland areas exceeding 1500 m in elevation–could be classified as in good or better condition.

Sulawesi’s biodiversity is partly the result of its strange geography. Noting that no location is more than 100 km from the coast, the authors call Sulawesi “a large island without an interior.” Map by Rhett A. Butler |

“Lowland forest is highly endangered and possibly doesn’t even exist on the island,” Cannon told mongabay.com.

Forest loss is so extensive on parts of the island that the authors expect the rate of forest conversion to slow substantially in the near future for the simple reason that most accessible sites have already been converted.

“Future large-scale conversion, if it occurs, will probably be of a different nature, in which marginal gains and specialized techniques are pursued,” the authors explain. “The majority of the forecasted conversion occurs in the southwestern arm, where disturbance has already been quite heavy and much of the remaining forest is fragmented and vulnerable to conversion.”

A road map for conservation efforts

Despite the sobering findings, the authors say the maps will help improve conservation efforts, even in cases where conservation organizations are taking different approaches to preserving ecosystems and biodiversity on the island.

“We feel that no single strategy for developing priorities can supply appropriate results for all conservation objectives in all locations,” the researchers write. “Additionally, we feel that all conservation organizations should not join together under the exact same agenda but should each pursue their own agenda, in collaboration and cooperation with other groups. In this way, efforts will be diversified.”

The babirusa or pig-deer (Babyrousa babyrussa) is one of Sulawesi’s best known and most charismatic animals. Belonging to the big family, the babirusa is endemic to the tropical forests of the island. Photo by Rhett A. Butler |

“Our map of important conservation frontiers on the island of Sulawesi, including the detailed geographic locations of major frontlines within these sites, provides an immediate and pragmatic tool for developing a wide variety of strategies,” they continue. “Our map is based upon transparent reasoning, involves a wide range of remotely sensed parameters and models, and allows each site and frontline to be categorized according to specific aspects of its landscape setting and forest cover status. Using our results as a base map, any conservation organization can readily target those areas that supply the best set of objectives for their own specific conservation values, whether it is to conserve habitat or prevent extinction of a particular group of organisms.”

The flexible nature of the map has applications beyond Sulawesi. Cannon said the methodology can be applied in other regions, especially in places where biodiversity is poorly known but threatened.

“Conservation strategies are obviously multivariate and each local situation demands a unique set of priorities and objectives,” Cannon explained via email. “Our ranking system was designed to be flexible and modular, so that resources managers can choose their own set of priorities. They can also easily add components to the ranking system, for example the distribution of important vertebrates, like the anoa. There will not be one solution or one algorithm to choose conservation priorities at all geographic levels or in all landscape settings. But, a comprehensive base map is essential for choosing the best set of priorities and not just the easiest from a logistic or historical perspective.”

Canon said that while much of the focus in conservation biology has traditionally been on large parks and protected areas, the maps reveal that fragments of forest can be particularly important.

“A few small areas of forest ranked quite high in our analysis. We do feel that these small fragments, if they can be protected from conversion and biological erosion is not allowed to progress, they can act as kernels from which the landscape can be regenerated and they have been shown to be key points of gene flow, as vertebrates and insects move between patches,” he explained. “While playing around with the ranking system, I took the perspective of a resource manager who wants to save the ‘most vulnerable’ and a tiny little recreation park near Makassar came out on top. While the forest is fairly degraded, it remains one of the few examples of lowland forest on alluvium and it is critically vulnerable. I think that these types of areas should be quite high on everyone’s list of priorities…. many large protected areas are not particularly vulnerable because they were chosen to be protected due to their inaccessibility or unprofitability.”

Making decisions when data is incomplete

In a departure from other surveys, but important given inconsistent data on the distribution and abundance of biodiversity on Sulawesi, the map excludes biological considerations, instead focusing on forest condition and other factors. The authors say that including questionable data can do more harm than good when attempting to prioritize conservation sites.

Most of Sulawesi’s mangroves have been converted for rice farming, aquaculture or other uses. Photo by Rhett A. Butler |

“Heavily weighting biotic endemism or species richness, particularly when reliable data are only available for higher trophic level organisms, likely skew conservation priorities away from more fundamental aspects of the landscape, like overall forest integrity, its proclivity to change, and the endangerment of poorly sampled and understood forest types,” they explain. “Additionally, placing such emphasis on species richness and endemism can lead to a distortion of species concepts… Our results capture many of the conservation objectives central to most conservation organizations… without explicitly incorporating them into the design of the ranking system. In the future, the modular and flexible nature of this ranking system can easily be adapted to reliable biotic data as they become available..”

“This type of multifaceted understanding should provide conservation strategists a sound footing in the identifying the social, economic, and political drivers of land-use change in and around important high conservation value areas,” they add.

“Sulawesi needs more attention from the conservation organizations around the world,” said Cannon. “It represents a truly unique ecoregion, with examples like the anoa and babirusa just representing the tip of the iceberg of the endemic biodiversity. Because of the crazy geography of the island and its richness in heavy metals, like nickel, most areas are exposed to conversion. There is also an incredibly rich set of human cultures, also vulnerable to extinction, like the Wana people in Morowali.”

CITATION: Charles H. Cannon, Marcy Summers, John R. Harting, and Paul J.A. Kessler (2007). “Developing Conservation Priorities Based on Forest Type, Condition, and Threats in a Poorly Known Ecoregion: Sulawesi, Indonesia”. Biotropica online 25 May to June 25, 2007.