U.S. ethanol may drive Amazon deforestation

U.S. ethanol may drive Amazon deforestation

mongabay.com

May 17, 2007

Ethanol production in the United States may be contributing to deforestation in the Brazilian rainforest said a leading expert on the Amazon.

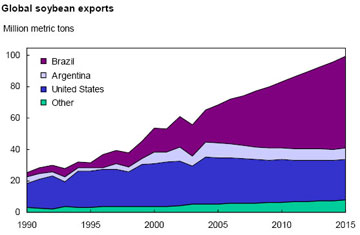

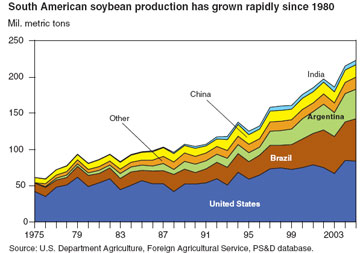

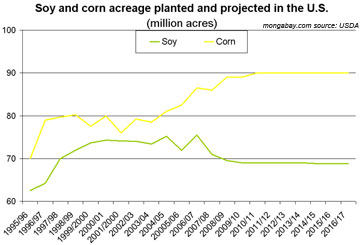

Dr. Daniel Nepstad of the Woods Hole Research Center said the growing demand for corn ethanol means that more corn and less soy is being planted in the United States. Brazil, the world’s largest producer of soybeans, is more than making up for shortfall, by clearing new land for soy cultivation. While only a fraction of this cultivation currently occurs in the Amazon rainforest, production in neighboring areas like the cerrado grassland helps drive deforestation by displacing small farmers and cattle producers, who then clear rainforest land for subsistence agriculture and pasture.

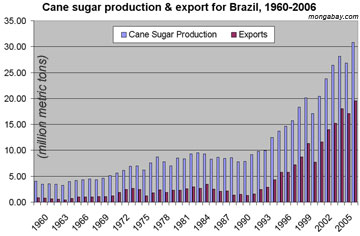

“We see soy prices going up partly because less soy is being grown in the U.S. as corn expands to meet the surging demand for the emerging ethanol industry,” Nepstad told mongabay.com in an interview appearing next week on the rainforest information site. “Similarly as sugar cane expands in southern Brazil, soy production is heading northward, encroaching on the Amazon.”

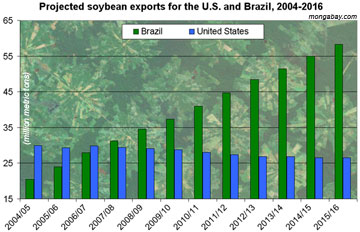

Projected soybean exports for Brazil and the United States, 2004-2015. Chart based on USDA data. Click to enlarge. |

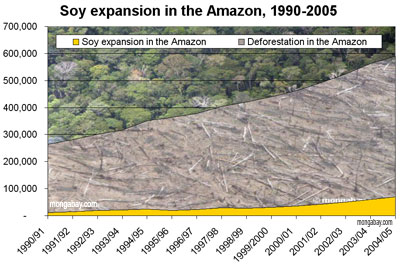

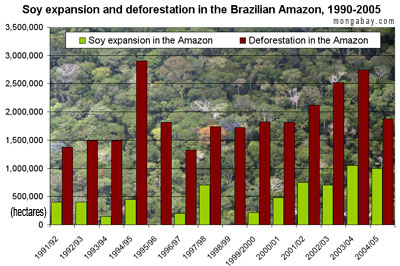

Soybean cultivation in the Amazon has expanded rapidly in recent years due to improved infrastructure in the region and rising demand for biofuels (soy can be used for biodiesel). Since 1990 the area of land planted with soybeans in Amazonian states has expanded at the rate of 14.1 percent per year (16.8 percent annually since 2000) and now covers more than eight million hectares. Soy is fast becoming a major driver of deforestation in the region, by pushing small-holder farmers into forest areas and providing impetus for infrastructure improvement projects–like the paving of Brazil’s Cuiabá-Santarém (BR-163) Highway–that spawn further forest clearing.

Note: some soybean farms are established on already degraded rainforest lands and neighboring cerrado ecosystems. Therefore it would be inappropriate to assume the area of soybean planting represents its actual role in deforestation. |

“Soybean farms cause some forest clearing directly,” said Dr. Philip Fearnside, a researcher at the Brazilian National Institute for Research in the Amazon (INPA) and a highly regarded Amazon scholar. “But they have a much greater impact on deforestation by consuming cleared land, savanna, and transitional forests, thereby pushing ranchers and slash-and-burn farmers ever deeper into the forest frontier. Soybean farming also provides a key economic and political impetus for new highways and infrastructure projects, which accelerate deforestation by other actors.”

The rapid expansion of soybean cultivation in the Amazon carriers other risks as well, according to research published last month in Geophysical Research Letters. Using experimental plots in the Amazon, a team of scientists led by Marcos Costa from the Federal University of Viçosa in Brazil found that clearing for soybeans increases the reflectivity or albedo of land, reducing rainfall by as much as four times relative to clearing for pasture land.

“This [effect] is related to the surface radiation balance,” explained Costa via email to mongabay.com. “Near the equator, rainfall is mainly produced by convective activity, that is, the hotter the surface the more rainfall you get. The soybean cropland, by having a higher albedo (reflectivity of the solar radiation) with respect to the original rainforest land cover, absorbs less energy, causing less convection and reduced rainfall.”

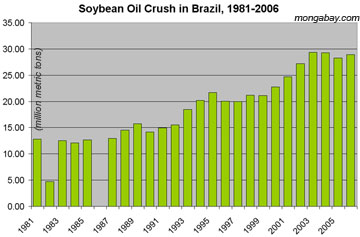

Brazil’s rapid rise as a producer of soybeans

Projected world share of the soybean market for Brazil and the United States, 2004-2015. Chart based on USDA data. Click to enlarge. |

Thanks to high demand and a new variety of soybean developed by Brazilian scientists to flourish in rainforest climate, soy production has boomed in the region in recent years as agricultural firms have converted extensive areas of rainforest and cerrado into industrial soybean farms. Brazil is expected to see its market share of soybean exports climb from around 31 percent in the 2004-2005 growing season to nearly 60 percent in 2015-2016. Meanwhile the U.S. will likely see its exports fall from 46 percent in 2004-2005 to less than 27 percent in 2015-2016, according to projections from the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). U.S. corn production and acreage is expected to increase as soybeans diminish.

Demand for corn is being driven by the surging ethanol industry in the U.S. Tuesday the USDA announced ethanol distillers will increase their share of domestic corn use by 58 percent this year, despite a projected record 12.46 billion-bushel corn crop. U.S. ethanol capacity currently stands at 6 billion gallons per year but the government hopes to double this by 2010.

Notes on Biofuels in Brazil

MORE SOYBEAN & AGRICULTURE CHARTS

Global soybean exports, 1990-2015. Chart courtesy of the USDA. Click to enlarge.

Global soybean production, 1975-2003. Chart courtesy of the USDA. Click to enlarge.

Projected world share of the soybean market for Brazil and the United States, 2004-2015. Chart based on USDA data. Click to enlarge.

Sugar production in Brazil, 1981-2005. Chart based on USDA data. Click to enlarge.

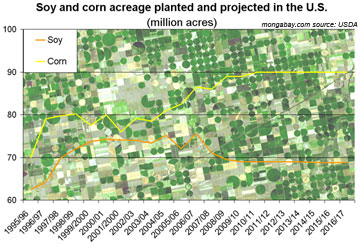

Planted and projected soy and corn acreage for the United States, 1995-2017, 2004-2015. Chart based on USDA data. Click to enlarge.

Planted and projected soy and corn acreage for the United States, 1995-2017. Chart based on USDA data. Click to enlarge.

DEFORESTATION IN BRAZIL: 60-70 percent of deforestation in the Amazon results from cattle ranches while the rest mostly results from small-scale subsistence agriculture. Despite the widespread press attention, large-scale farming (i.e. soybeans) currently contributes relatively little to total deforestation in the Amazon. Most soybean cultivation takes place outside the rainforest in the neighboring cerrado grassland ecosystem and in areas that have already been cleared. Logging results in forest degradation but rarely direct deforestation. However, studies have showed a close correlation between logging and future clearing for settlement and farming.