Reducing tropical deforestation will help fight global warming

Reducing tropical deforestation will help fight global warming

Rhett A. Butler, mongabay.com

May 10, 2007

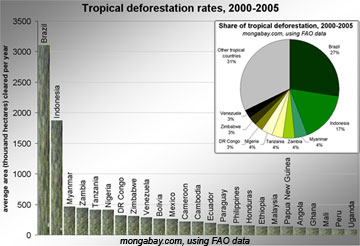

More scientists have joined the growing chorus to support a plan by developing countries to fight global warming by reducing deforestation rates. Tropical deforestation releases more than 1.5 billion metric tons of carbon into the atmosphere every year, though in some years, like the 1997-1998 el Niño year when fires released some 2 billion tons of carbon from peat swamps alone in Indonesia, emissions are more than twice that.

Writing in the journal Science, an international team of scientists argue that the “Reducing Emissions from Deforestation” (RED) initiative, launched in 2005 by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, is scientifically and technologically sound, and that political and economic challenges facing the plan can be overcome.

“Many of these countries resisted certain provisions of the Kyoto Protocol because they felt that it intruded on their national sovereignty,” said Dr. Christopher Field, director of Carnegie Institute’s Department of Global Ecology at Stanford University and a co-author on the policy article. “Now, they are ready and willing to address forestry strategies in a constructive manner, on their own terms. It is very encouraging.”

“For many developing countries, deforestation is their largest source of emissions,” added Peter Frumhoff, co-author and director of Science and Policy at the Union of Concerned Scientists. “The current negotiations represent a historic opportunity to help developing countries find economically viable alternatives to deforestation, and participate in the global effort to address climate change.”

The RED plan

When trees are cut greenhouse gases are released into the atmosphere — roughly 20 percent of annual emissions of such heat-trapping gases result from deforestation and forest degradation. Avoided deforestation is the concept where countries are paid to prevent deforestation that would otherwise occur. Funds come from industrialized countries seeking to meet emissions commitments under international agreements like the Kyoto Protocol. Policymakers and environmentalists alike find the idea attractive because it could help fight climate change at a low cost while improving living standards for some of the world’s poorest people, safeguarding biodiversity, and preserving other ecosystem services. A number of prominent conservation biologists and development agencies including the World Bank and the U.N. have already endorsed the idea. Even the United States government has voiced support for the plan.

While the initiative seems promising there have been significant questions, note the authors:

“First, are the potential carbon savings from slowing tropical deforestation sufficient to contribute substantially to overall emissions reductions? Second, is it likely that tropical forests (and the forest carbon) protected from deforestation will persist over coming decades and centuries in the face of some unavoidable climate

change?”

“The answer in both cases is a qualified ‘yes,'” Field said. “As with all measures to address global warming, the key is immediate and aggressive action.”

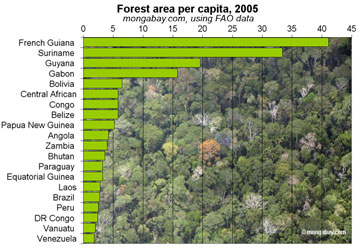

Tropical countries with the highest amount of forest per capita in 2005 based on data from the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). Image by Rhett A. Butler, click to enlarge |

Addressing the first questions, the authors found that reducing deforestation rates by 50 percent over the next century will save an average of about half a billion metric tons of carbon every year, enough to account for as much as 12% of the total reductions needed to meet the IPCC target of 450 parts per million of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere by the year 2100. They say that reducing deforestation as a means to cut emissions may be “among the least-expensive mitigation options available” with cost estimates at $20 or less per ton of carbon.

“Reducing tropical deforestation is key to decreasing global emissions,” said Katharine Hayhoe, a research associate professor in the Department of Geosciences at Texas Tech University and a co-author of the report. “The reductions we looked at are projected to cost less than $20 per ton of carbon dioxide. This makes slowing deforestation one of the most cost-effective measures to reduce our emissions globally, especially when compared to the cost of weaning ourselves off our dependence on fossil fuels.”

“Conserving tropical forests could ultimately be one of the cheapest ways we have available to slow global warming,” said Dr. William Laurance, a biologist with the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute who in 2006 was instrumental in leading the Association for Tropical Biology and Conservation (ATBC), the world’s largest scientific organization devoted to the study and wise use of tropical ecosystems, to pass a resolution in support of the RED initiative. “The costs of forest conservation are modest and deforestation is a massive source of emissions, so slowing deforestation is like plucking the low-hanging fruit—there’s a lot of benefit for not a lot of cost. And of course we’re not just storing carbon; we’re also saving the world’s most biologically important real estate, providing a place for local and indigenous peoples, and helping to stabilize delicate soils and reduce catastrophic flooding.”

“The positive impact of tropical forest conservation might be even bigger than the authors suggest,” Laurance continued. “A recent study by Bala et al. in PNAS suggests that, relative to temperate and boreal forests, tropical forests have a far bigger positive effect on global warming. Bala and his team evaluated only the consequences of deforestation not only for forest carbon storage, but also on for evapotranspiration—which produces planet-cooling cloud cover—and on changes in albedo (or heat-absorption). The net effect is that tropical forests may be even more important from a global-warming perspective than anyone had previously imagined.”

On the second question, the researchers say that climate forecasts show that tropical forests will continue to serve as a “sink” for carbon dioxide emissions provided that emissions can be kept under control. They say that while the efficiency of the tropical forest as a carbon sponge may diminish over time due to higher levels of atmospheric CO2, it will not disappear completely.

“A widely-discussed early study projected that business-as-usual increases in CO2 and temperature could lead to dramatic dieback and carbon release from Amazon forests, raising concerns that high sensitivity of tropical forests to climate change might compromise the long-term value of reduced deforestation, with dieback releasing much of the carbon originally conserved,” they write. “However, of 11 coupled climate-carbon cycle models using the IPCC’s mid-to-high range A2 emissions scenario, 10 project that tropical forests continue to act as carbon sinks, albeit declining sinks, throughout the century.”

“The moderate sensitivity indicated by the new results suggests that reducing deforestation can result in long-term carbon storage, even with substantial climate change. Aggressive efforts to reduce industrial and deforestation emissions would likely further reduce the rate of decline and risk of reversal of the tropical sink,” the authors continued.

Hopeful political and economic climate for RED

Because the RED initiative was put forth by a group of tropical countries, the Coalition of Rainforest Nations, it enjoys relatively broad support among developing countries. Nevertheless, some countries–notably Brazil–and industry interests (especially forestry and agriculture) have expressed reservations about the plan, arguing that it could stymie economic opportunities based on forest exploitation and resource extraction. The authors say these fears can be allayed through policy measures.

“In some countries, it may be possible at relatively low cost to reduce emissions from deforestation and forest degradation that provide little or no benefit to local and regional economies,” they write. “For example, reducing accidental fire and eliminating forest clearing on lands that are inappropriate for agriculture are two promising low-cost options for reducing greenhouse gas emissions in Brazil and Indonesia.”

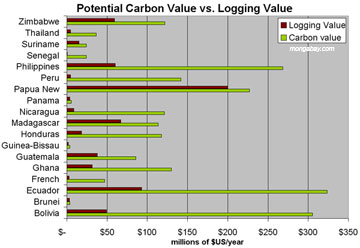

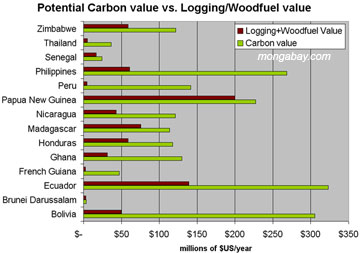

“In forests slated for timber production, for example, moderate carbon prices could support widespread adoption of sustainable forestry practices that both directly reduce emissions and reduce the vulnerability of logged forests to further emissions from fire and drought exacerbated by global warming. On forested lands threatened by agricultural expansion, financing could provide significant incentives for forest retention and enable, for example, more effective implementation of land-use regulations on private property and protected area networks.”

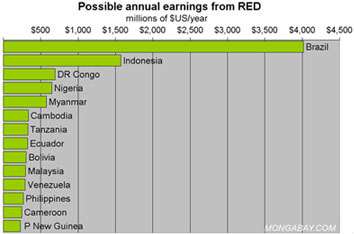

While there may be still be political obstacles to overcome, economics could prove to be a driver of the initiative if industrialized countries are serious about controlling global greenhouse gas emissions. Their demand for lost-cost carbon emissions offsets could be a boon to tropical countries, generating revenue sometimes in excess of what could be earned from conventional, albeit unsubsidized, logging and agriculture. At the same time, both industrialized counties and the developing world, would benefit from the services provided by extant forests.

“Beyond protecting the climate, reducing tropical deforestation has the potential to eliminate many negative impacts that may compromise the ability of tropical countries to develop sustainably, including reduction in rainfall, loss of biodiversity, degraded human health from biomass burning pollution, and the unintentional loss of productive forests,” the authors write.

They conclude by saying financial incentives for forest preservation will be key to fighting climate change and helping poor countries ramp up their economies in a sustainable manner.

“Providing economic incentives for the maintenance of forest cover can help tropical countries avoid these negative impacts and meet development goals, while also complementing aggressive efforts to reduce fossil fuel emissions. Industrialized and developing countries urgently need to support the RED policy process and develop effective and equitable compensation schemes to help tropical countries protect their forests, reducing the risk of dangerous climate change and protecting the many other goods and services that these forests contribute to sustainable development,” they conclude.

NOTES

Authors on the paper are Raymond Gullison of the University of British Columbia, Canada; Peter Frumhoff of the Union of Concerned Scientists; Christopher Field of the Carnegie Institute’s Department of Global Ecology at Stanford University; Josep Canadell of the Global Carbon Project, Australia; Christopher Field of the Carnegie Institution; Daniel Nepstad of The Woods Hole Research Center; Katharine Hayhoe of Texas Tech University; Roni Avissar of Duke University; Lisa Curran of Yale University; Pierre Friedlingstein of IPSL/LSCE, France; Chris Jones of the Hadley Centre for Climate Prediction and Research, United Kingdom; and Carlos Nobre of Centro de Previs?o de Tempo e Estudos Climaticos, Brazil.

In a report published last year the World Bank estimated that land worth $200-500 per hectare as pasture could be worth $1,500-$10,000 if left as intact forest and used to offset carbon emissions from industrialized countries.

CITATION: R.E. Gullison, et. al. (2007) Tropical Forests and Climate Policy. Science / www.sciencexpress.org /10 May 2007 / Page 1/ 10.1126/science.1136163

Related articles

|

Amazon rainforest locks up 11 years of CO2 emissions

(5/8/2007) The amount and distribution of above ground biomass (or the amount of carbon contained in vegetation) in the Amazon basin is largely unknown, making it difficult to estimate how much carbon dioxide is produced through deforestation and how much is sequestered through forest regrowth. To address this uncertainty, a team of scientists from Caltech, the Woods Hole Institute, and INPE (Brazil’s space agency), have developed a new method to determine forest biomass using remote sensing and field plot measurements. The researchers say the work will help them better understand the role of Amazon rainforest in global climate change.

|

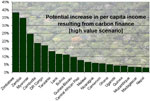

Avoided deforestation could send $38 billion to third world under global warming pact

(10/31/2006) Avoided deforestation will be a hot point of discussion at next week’s climate meeting in Nairobi, Kenya. Already a coalition of 15 rainforest nations have proposed a plan whereby industrialized nations would pay them to protect their forests to offset greenhouse gas emissions. Meanwhile, last month Brazil — which has the world’s largest extent of tropical rainforests and the world’s highest rate of forest loss — said it promote a similar initiative at the talks. At stake: potentially billions of dollars for developing countries. When trees are cut greenhouse gases are released into the atmosphere — roughly 20 percent of annual emissions of such heat-trapping gases result from deforestation and forest degradation. Avoided deforestation is the concept where countries are paid to prevent deforestation that would otherwise occur. Policymakers and environmentalists alike find the idea attractive because it could help fight climate change at a low cost while improving living standards for some of the world’s poorest people and preserving biodiversity and other ecosystem services. A number of prominent conservation biologists and development agencies including the World Bank and the U.N. have already endorsed the idea.

Carbon trading could save rainforests

(4/12/2006) A new rainforest conservation initiative by developing nations offers great promise to help slow tropical deforestation rates says William Laurance, a leading rainforest biologist from the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute in Panama, in an article appearing Friday in New Scientist.

Scientists endorse plan to save rainforests through emissions trading

(5/19/2006) The Association for Tropical Biology and Conservation (ATBC), the world’s largest scientific organization devoted to the study and wise use of tropical ecosystems, has formally endorsed a radical proposal to help save tropical forests through carbon trading. Under the initiative proposed by an alliance of fifteen developing countries led by Papua New Guinea and Costa Rica, tropical nations that show permanent reductions in deforestation would be eligible to receive international carbon funds from industrial nations who could purchase carbon credits to help them meet their emissions targets international climate agreements like the Kyoto Protocol.

World Bank says carbon trading will save rainforests

(10/23/2006) Monday the World Bank endorsed carbon trading as a way to save tropical rainforests which are increasingly threatened by logging, agricultural development, subsistence agriculture, and climate change itself. The World Bank report comes on the heels of a proposal by a coalition of developing countries to seek compensation from industrialized countries for conserving their rainforests to fight global warming. Brazil is expected to announce a similar plan at upcoming climate talks in Nairobi.

Indonesia wants to be paid for slowing deforestation

(1/31/2007) Indonesia voiced support for a proposal by a coalition of developing countries seeking compensation for forest conservation, according to a report from Reuters. Rachmat Witoelar, Indonesia’s minister of the environment, told Reuters that poor countries should be paid for conserving forests and the services they provide the world.

|

Higher temperatures slow tropical tree growth

(4/23/2007) Climate change may be reducing growth rates of tropical rainforest trees, a development that could have widespread impacts for biodiversity, forest productivity, and even climate change itself, according to new research published in Ecology Letters.