An interview with IT conservation expert Ken Banks

Cell phones have been adopted at a pace unmatched by any technology in the history of mankind. While conventional use of these devices continues to expand, mobile phones are also increasingly being viewed as tools for conservation and development.

Ken Banks, currently a Visiting Fellow on the Reuters Digital Vision Program at Stanford University, understands this well. Banks established kiwanja.net as hub for the latest information on how technology, in particular mobile phones, can be applied to tackle issues of economic empowerment, conservation, education, human rights and poverty alleviation.

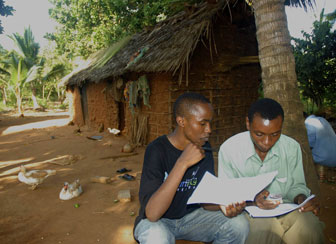

Preparing a conservation plan in Kenya. Courtesy of the Kiwanja mobile image gallery |

Banks says that the development of low-cost handsets and the spread of second-hand phones into emerging markets like South Asia and Africa — one of the fastest growing markets with well in excess of 125 million subscribers — is generating a revolution in how organizations approach conservation projects. Mobile phones offer these groups new ways to engage stakeholders, while reducing overhead costs and inefficiencies. The technology can even allow them to track animals, protect parks, and conduct surveys in some of the world’s most remote forests.

In April 2007 Banks spoke with mongabay.com about his work.

Mongabay: How did you become involved with applying mobile technology to conservation and development?

Banks: Originally I was in the information technology (IT) industry but my mother and grandparents have always been very keen on nature and the environment. I must have inherited the family gene for nature because ever since I was a child I’ve been fascinated by the outdoors.

Ken Banks in Mana Pools, Zimbabwe |

The experience that really cemented my interest in conservation and development was a trip to Zambia in 1993. I was awarded a place on a Jersey Overseas Aid project where I helped build a school. While I was there, I started to think about where all the aid money was going and why it didn’t seem to be particularly effective. I began to look at the practical side of conservation and development efforts, when previously my interest had been primarily in wildlife – the kind of stuff you saw on David Attenborough’s shows and other TV programs. In 1995 I went back to Africa to help build a hospital in Uganda. By then I was really quite captivated and I knew it was something I wanted to be involved in.

Mongabay: So it sounds like your first foray into this kind of work was from a humanitarian angle?

Banks with an infant during his overseas aid trip to Uganda, in 1995 |

Banks: Well yes, these were the opportunities that were available to me at the time from a foreign standpoint. In Jersey the IT company I was working for had Jersey Zoo among their clients, now known as Durrell Wildlife. During my 3 to 4 years involvement there, I got very interested in conservation from a developing country standpoint – not just what was going on in Jersey but the wider global issues. It gave me the opportunity to tap into some of the real leaders in the field and see captive breeding and habitat conservation programs firsthand. I also benefited from the excellent learning center at Durrell, where they train conservation workers from developing countries in the latest conservation techniques. It’s through these experiences that my IT background really began to blend into conservation and development work. It was a great time and I was very fortunate to have experienced it.

Mongabay: When did you go off on your own?

Banks: I left my job in Jersey in 1996 to go the University of Sussex to pursue a degree in Social anthropology with development studies. I sold everything I owned at that point and left for the UK with two suitcases. That was the beginning of the journey. I formed kiwanja.net in 2003 after I returned from a year working with primates in Nigeria.

Mongabay: What is it that you do through kiwanja.net?

Banks: kiwanja.net helps local, national and international nonprofit organizations make better use of information and communications technology in their work. While the site is more of an information resource, I generally function as an intermediary between the technology – especially mobile technology – and conservation or development groups. You’ll see organizations like the Gates Foundation looking at technology use in developing countries. I help put them in contact with people in the field as well as some of the technology and applications under development. Part of what I do is match-making in a sense. I have also developed mobile applications for use in conservation and development, such as FrontlineSMS.

Mongabay: What advantages do mobile technologies offer conservation and development groups?

Cheap mobile phones are now sold in markets all over the world. Courtesy of the Kiwanja mobile image gallery |

Banks: While large numbers of organizations have been trying to promote the spread of the Internet in rural parts of developing countries, penetration rates are still pretty low in many areas. Mobile phones, however, have been spreading rapidly and today are nearly ubiquitous in some countries, leapfrogging the number of land lines in a matter of 3 or 4 years. We now have a situation where even if people don’t themselves own a cell phone, they can easily find access to one through another member of the community, or through various Village Phone schemes.

Because of their widespread adoption, we are now seeing mobile phones being used for many conservation and development applications. Many center around improving communication between stakeholders and NGOs – for example, sending out alerts on impending natural disasters like tsunami and hurricanes, or wildlife alerts, or posting job openings or health messages. The advantages of text messaging is that it is very quick, generally cheap, and direct. Most people read the text messages they receive, unlike spam. It also works on every phone regardless of form factor – a critical issue in areas where a lot of the phones can be as much as 5 to 7 years old. These phones are often useless for surfing the Internet but they work fine for SMS.

As for conservation applications, I focus on the improved communication capabilities. Unlike in the past where you had government agencies evicting people from their land in order to set up protected areas, today it is realized that conservation efforts must involve local people, otherwise you only disenfranchise them and drive them to oppose conservation efforts. Now with the rise of community-based conservation and integrated conservation and development projects, communication can reduce these issues – mobile phones allow us to open channels that were never before possible. For example, in Kruger National Park (South Africa), the park management used to have to send a Land Rover out to the 18 different communities living around the park to inform them of meetings, give them latest news, and so on. If a meeting was canceled or changed, the ranger had to go back out. It might take days to spread the world. Today it is possible to simply broadcast a text message. We can even set up a database that captures text responses from various communities on whether they will be able to attend or how they would vote on a particular initiative. This functionality frees up a lot of resources for more meaningful and productive activities from both the parks’ and community’s perspective.

Organizations are also finding that mobile phones can serve as an activism tool. SMS messaging can be used to organize petitions and plan demonstrations. In fact, the tool is so powerful that it is even a concern for repressive governments. In recent elections in both Cambodia and Iran the government shut down messaging servers to prevent demonstrators from organizing and campaigning. They didn’t want to take any chances after what happened in Ukraine, where the Orange Revolution may not have been possible without text messaging services, and the Philippines, where President Estrada was toppled by gatherings organized by text messaging campaigns.

In Zimbabwe journalists are now using text messaging to distribute news since President Robert Mugabe clamped down on e- mail and shortwave broadcast media.

Mongabay: It sounds like most of these applications are top-down approaches. Are the examples of user-generated content?

Banks discussing technology use at Johannesburg Zoo in 2005 |

Banks: Definitely, but it’s in the early stages in many cases. The release of my FrontlineSMS system is an attempt to bring the technology into hands of the users, and to promote more of a bottom-up approach. In terms of user-generated content, current ‘hot’ applications include SMS blogging, which really blossomed during last year’s Israel-Lebanon conflict. We saw news being generated by SMS messaging as Beirut was getting bombed. The real-time nature of the posts provided insight on what was really happening on the ground. This type of reporting – citizen journalism – is very much technology driven and the BBC, for example, regularly request people near the thick of the action, particularly with camera-phone images or mobile video, to send them in.

From a conservation perspective, mobile phones are increasingly used for surveys and monitoring. In Kenya, for example, Save The Elephants are using GPS/GSM collars to track elephants. Compared to the alternatives it’s cheap, real-time, and doesn’t depend on ARGOS satellites which drives up complexity and costs. These devices not only help the organisation understand how elephants use their environments, but it also provides farmers and villagers with an early-warning system so they can protect crops from being eaten and trampled. Human elephant conflict is still a big issue in many countries. In South Africa, a wireless animal tracking system provided by African Wildlife Tracking helps researchers track wildlife in game reserves. Once fitted with a tracking device, text messages are sent to the device to pinpoint the longitude and latitude of the animal. Again this is much simpler and cost-effective than involving multi-million dollar satellites, or more time-consuming VHF tracking systems.

Mongabay: What are the biggest challenges to your work?

Banks: The big problem I see is that people are generally reluctant to share. It’s hard to find examples of mobile phone applications for conservation so you see a lot of wheel-spinning and duplication. The mobile phone is being touted as the device that will bridge the digital divide, so there should be more collaboration between organizations trying to address these important issues. You know, how many ‘ICT for development’ portals do we need? Rather than going it alone, I think peoples’ first instincts should be to look at collaboration wherever possible.

Mongabay: So this is where you come in with kiwanja.net?

Banks with renowned British naturalist, Sir David Attenborough |

Banks: Yes, kiwanja is developing into a bit of an information hub for the latest news on applying mobile technology to conservation and development, and crucially for me this has been needs-driven by the community, not something that I think is needed. The mobile applications database contains details of more than 200 projects from around the world that use mobile technology in fields including human health, economic empowerment, conservation, education, human rights and poverty alleviation, and it is growing all the time. I get emails from researchers telling me how valuable it has been in their work. There is also an image gallery showing mobile technology in action in developing countries. Again, I was concerned about the lack of images which many non-profits needed for campaigning literature, project proposals, websites and so on. Before that, most of the good images I was finding came at a price, whereas mine are free to use. Openness, sharing and transparency are key pillars of my work.

Mongabay: How are mobile phones used for health?

Banks: In Nigeria and India we are seeing government agencies and NGOs use SMS as a health education messaging application. There are also groups using mobiles and mobile networks for disease surveillance. What just a few years ago took three months to report is now almost instantaneous. Spreading the word of outbreaks in remote areas saves lives.

One interesting health application is the SIMpill which helps with the problem of people not finishing their course of antibiotics. This of course only produces drug-resistant strains that are more difficult to treat. SIMpill is an SMS-enabled pill bottle which, when opened, delivers a text message to a central server. Each SMS is time stamped and kept as a record of the patient taking their medication. The doctor is warned via text message if the patient is not taking their medication properly.

Mongabay: In what other ways can SMS and mobile telephony be used in conservation?

Banks: We are seeing SMS used in both fundraising and awareness-raising campaigns and for more conservation-specific applications.

Girl in Mozambique. Photo by Ken Banks. |

One project I was heavily involved in was wildlive! , a service which promoted global conservation by providing news and information on various issues through peoples’ handsets. It also had a direct fundraising angle through the sale of conservation-themed wallpapers, ringtones and games. Funds raised went to Fauna & Flora International, a UK-based organization, and directly to the conservation projects being promoted.

In Sumatra, tiger researcher Debbie Martyr kept a live field diary that was broadcast via a mobile internet site. Her experiences included live sting operations which used camera-phones to capture poachers and illegal fur traders in action.

In the Okapi Wildlife Reserve of the Democratic Republic of Congo, satellite phones enable patrols to text message their GPS location along with a short message from anywhere in the Reserve. The base operator can then call the patrol teams in an emergency, resulting in a much quicker response to threats to the Reserve.

Mongabay: What do you think about the Amazon Conservation Team’s (ACT) project in the Amazon which uses GPS and Google Earth to map tribal lands and protect the forest against illegal encroachment? It’s not mobile technology but it seems to have some parallels.

|

Amazon natives use Google Earth, GPS to protect rainforest home. Deep in the most remote jungles of South America, Amazon Indians (Amerindians) are using Google Earth, Global Positioning System (GPS) mapping, and other technologies to protect their fast-dwindling home. Tribes in Suriname, Brazil, and Colombia are combining their traditional knowledge of the rainforest with Western technology to conserve forests and maintain ties to their history and cultural traditions, which include profound knowledge of the forest ecosystem and medicinal plants. Helping them is the Amazon Conservation Team (ACT), a nonprofit organization working with indigenous people to conserve biodiversity, health, and culture in South American rainforests. |

Banks: ACT’s project is very interesting. What makes it particularly exciting from my perspective is that it is very anthropological. Conservation is not just about working with wildlife, it’s also about working with people so anthropology, with its human-centred focus, is of particular relevance. For many people it’s still not an obvious fit, particularly when technology is involved. I’ve been speaking at companies, workshops and conferences a lot about this lately.

What I really like about the ACT project is that it’s needs-driven, based on needs of the local people, not donors. The users – in this case the Amazonian tribes – see the relevance of the technology so they embrace it, and the technology fits in seamlessly with what they are trying to achieve. More remarkable is that the program also promotes cultural preservation in a climate where culture loss is a serious concern.

Did you see the announcement on the Darfur features added to Google Earth this week? What we are seeing is the creation of “communities of consciousness” that develop an interest and awareness in the human stories behind events. It’s a great way to build strong support for an issue. I think ACT could do a similar thing if the tribes wanted to post up some of their sacred stories so that the general public could get a better understanding of their history and culture. It could serve as a rallying point for their concerns over forest development. Maybe they’re already doing this.

While there are always concerns over whether technology will drive people away from their traditional lifestyles, in cases such as this technologies can provide new opportunities whilst allowing people to continue to live in traditional ways. As Mark Plotkin at ACT has said, it’s the best of both worlds.

Mongabay: What are your thoughts on the “One Laptop Per Child” (OLPC) initiative that provides low-cost (i.e. $100), durable laptops to children in developing countries?

The $100 laptop. Photo courtesy of One Laptop per Child. |

Banks: I think it is an interesting experiment – which is basically what it is – but the jury is still out on OLPC. Personally I have problems more with the process than the product. One of the best arguments I’ve heard on why it has the potential to be ethically problematic is that you are asking some of the world’s poorest countries to foot the bill for what is essentially a prototype. These governments will be spending hundreds of millions of dollars each, up front, to fund an unproven technology. It is fraught with risk and on a production scale that has never been attempted before in the ICT for development field. While it may turn out that these concerns are totally unfounded, it seems like an expensive way of “having a go” – especially for governments least able to afford it. Comparably, if you look at the mobile phone it is ubiquitous, cheaper, and less complex. We’re seeing more companies and organizations developing emerging market handsets based on 2, 3 or 4 years of real-world experience. You can’t say that about OLPC. OLPC can’t really compare itself to anything, although OLPC 2.0 (if I can call it that!) would be able to.

But, to be fair, OLPC might well be a revolution – I’m not trying to knock the project. You have to credit the developers for going out there and trying to do something bold for the benefit of humankind.

Interestingly, India actually turned down the project. Instead, it is evaluating home grown technologies (called NetTV and NETPC), which begs the question of whether a single product can really work on a global scale in emerging markets. The world is not homogenous and technology definitely needs to be tested out in the field. I’ve often seen a disconnect between technology developers and the real-world use of their products. At a recent conference I attended in India for W3C, there was very little emphasis on the user – it was all about the technology. There’s a big difference between how something is used in an airport lounge and how well it might work in a remote village with limited power supply, 100-degree heat, dust storms and a semi-literate user. For many developers, how their technology works in an emerging-market context is generally an after-thought.

In the places where I work, it is the first question I tend to ask.

Ken Banks is currently a Visiting Fellow on the Reuters Digital Vision Program at Stanford University.