Bad news for frogs; amphibian decline worse than feared

Chilling new evidence suggests amphibians may be in worse shape than previously thought due to climate change. Further, the findings indicate that the 70 percent decline in amphibians over the past 35 years may have been exceeded by a sharp fall in reptile populations, even in otherwise pristine Costa Rican habitats. Ominously, the new research warns that protected areas strategies for biodiversity conservation will not be enough to stave off extinction. Frogs and their relatives are in big trouble.

Writing in the Early Edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), a team of researchers led by Steven M. Whitfield of Florida International University, found that amphibian and reptile populations declined by 75% since 1970 in the protected old-growth lowland rainforest of La Selva Biological Station in Costa Rica. The declines only occurred in primary forests — neighboring abandoned cacao plantations did not suffer diminished populations.

Oophaga pumilio, the strawberry poison frog, is one of a number of species of amphibians and reptiles declining in lowland forests of Costa Rica. Image credit: Steven M. Whitfield. |

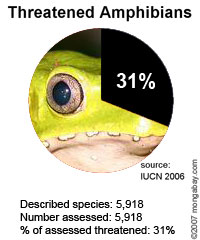

Scientists say amphibians — cold-blooded animals that include frogs, toads, salamanders, newts and caecilians — are under grave threat due to climate change, pollution, and the emergence of a deadly and infectious fungal disease, which has been linked to global warming. According to the Global Amphibian Assessment, a comprehensive status assessment of the world’s amphibian species, one-third of the world’s 5,918 known amphibian species are classified as threatened with extinction. Further, more than 120 species have likely gone extinct since 1980. Scientists say the worldwide decline of amphibians is one of the world’s most pressing environmental concerns; one that may portend greater threats to the ecological balance of the planet. Because amphibians have highly permeable skin and spend a portion of their life in water and on land, they are sensitive to environmental change and can act as the proverbial “canary in a coal mine,” indicating the relative health of an ecosystem. As they die, scientists are left wondering what plant or animal group is next.

|

The results from the new study are particularly disturbing because they were largely unexpected. To date most observed amphibian declines have occurred in temperate regions or mountainous areas in the tropics. These have been attributed to the parasitic chytrid fungal infection, but no evidence of chytridiomycosis was found by Whitfield and his colleagues. Further, the research reports a simultaneous fall in reptile populations, a finding that has not been previously documented and suggests that something else is amiss in the ecosystem.

“The leaf litter guild of the lizard fauna represents the vertebrate group most ecologically similar to litter amphibians, and both terrestrial frogs and terrestrial lizards use similar habitats, microhabitats, and prey,” the researchers write. “Because these two groups differ in physiological susceptibility to factors associated with amphibian declines (e.g., pesticide exposure or emerging infectious diseases), these ecologically similar lizards provide an invaluable contrast for sorting hypotheses about mechanisms driving amphibian declines.”

Due to the pristine nature of the site, the researchers were able to dismiss a number of possible explanations for the dramatic decline in reptile and amphibian populations, including habitat modification, fragmentation, pesticides, and, of course, the deadly chytrid pathogen, since it does not affect reptiles or occur in the study area.

Instead, the researchers propose climate change is agent behind the population collapse, arguing that a reduced number of rainless days combined with rising temperatures has negatively impacted the amount of standing leaf litter, a critical microhabitat for the subject “herps.”

|

Their results differ markedly from those in other parts of the world where documented amphibian declines have occurred suddenly, sometimes in a matter of months.

“In contrast to these sudden decline events,” they write, “we demonstrate… that community-wide gradual declines also may occur.”

Faring worst in the study were salamanders, which declined by an average of 14.5 percent per year since 1970. Frogs declined by 4 percent, while lizard density fell by 4.5 percent per year.

“Unfortunately, we have no idea how to explain differences in rate of decline between species,” Whitfield told mongabay.com via email. “Salamanders are quite susceptible to the pathogenic chytrid fungus that has wiped out species of amphibians in the mountains, but this fungal disease can’t explain all our trends. Further, aquatic species are most susceptible to this fungus, and these salamanders never enter water (they even lay eggs on land). At this point, we have way more questions than answers.”

Data deficiency spawns complacence

The researchers add that they don’t know whether similar declines are occurring elsewhere.

“Sadly, the dramatic declines we report here can only be considered slow in comparison to these nearly instantaneous extinction events,” they write. “It is currently impossible to determine how often gradual community-wide declines such as the one we report here are actually occurring, because trends such as those we report are impossible to detect without longterm abundance-based data on population densities collected by using consistent methodology. Although such datasets are exceptionally rare, they will be critical to understanding the full extent of the amphibian decline crisis.”

The authors warn that this lack of data may even be undermining conservation assessments by shifting perceptions on the historic levels of species richness in the ecosystem.

“Furthermore, the lack of historic data on population densities may lead to naive or inappropriate assessments of conservation status, a phenomenon known as shifting baselines syndrome,” they write. “Without robust historical datasets indicating precipitous declines, current densities of amphibians and reptiles could be used to suggest that amphibian and reptile populations at La Selva are free from conservation risks. Indeed, all but one of the amphibian species for which we report persistent decade-long declines in protected old-growth rainforests are listed as ‘least concern’ in the IUCN Red List.”

The authors imply that lack of data may be spawning complacence.

“Our data raise the worrying possibility that systematic declines in amphibian populations do not occur only in cool climates, but that because declines occurring in cooler sites occur more quickly, these are the only habitats where they are detected. Our data indicate that even populations of amphibians for which specific threats have not been identified may nonetheless be suffering dramatic decline, and that such populations may be considered stable because of lack of long-term data, not lack of threats.”

Saving amphibians from extinction

The authors say that because little is known about the nature and extent of amphibian decline it is difficult to prescribe conservation strategies for saving amphibians from extinction.

“At the moment, I can’t see our recent findings immediately changing conservation policies. We don’t really understand what has caused the declines that we’re reporting, and it is difficult to design effective conservation strategies against threats we can’t be reasonably confident about,” Whitfield said. “Still, protecting habitat is by far the most effective means for protecting biodiversity.”

Earlier this year scientists met in Atlanta to devise last minute plans to save disappearing amphibians from extinction. The group, which called itself the Amphibian Ark, aims to save threatened amphibians by asking zoos, aquariums, and botanical gardens to act as sanctuaries for disappearing frogs, salamanders, newts, and caecilians. These facilities would serve as a proverbial “ark” to protect amphibians until scientists figure out a way to stop the killer chytrid fungus and other threats. While such efforts are already under way with a handful of species at the Bronx Zoo in New York (Kihansi Spray Toad) and the Houston Zoo (Panamanian Golden Frog), the expanded effort for hundreds of species is expected to cost $400-500 million.

Whitfield says the AArk concept may help save some of the most threatened species but still falls short of an ideal solution.

“For certain species — those that are hardest hit by global declines — the “ark” is probably the only feasible thing to do to prevent complete extinction,” he said. “We can predict with reasonable accuracy which species are likely to go extinct (stream-inhabiting mountain frogs), we know that these extinctions can happen very quickly, and it therefore seems it would be irresponsible not to establish captive populations of these species. This is certainly only part of the solution, however, and intensive captive breeding programs are an expensive way to protect species. We still desperately need more research into the causes of global amphibian declines. So the “ark” is certainly not an ideal conservation solution, but may be a desperate necessity.”

Kevin C. Zippel, Program Officer for the Amphibian Ark, adds that the world must act soon to protect amphibians from extinction.

“No one will dispute that the best place to conserve species is in the wild, but currently we cannot control threats like chytrid fungus and global warming,” Zippel told mongabay.com. “We have a simple choice: allow threatened species to go extinct, or provide them temporary sanctuary in captivity until those in situ threats can be mitigated. The responsible choice is clear.”

“Our greatest challenge is not the husbandry or science, it is getting the necessary support from government and society at large to support a rapid repsonse before we lose much of this spectacular vertebrate class… Unless we intervene now, we will not have any options in the future.”

CITATION: Steven M. Whitfield, Kristen E. Bell, Thomas Philippi, Mahmood Sasa, Federico Bolaños, Gerardo Chaves, Jay M. Savage, and Maureen A. Donnelly (2007). Amphibian and reptile declines over 35 years at La Selva, Costa Rica. PNAS Online Early Edition for the week of April 16-20, 2007. www.pnas.orgcgidoi10.1073pnas.0611256104