Nairobi talks made progress on forest conservation for global warming emissions credits

Interview with carbon finance analyst Johannes Ebeling:

Nairobi talks made progress on forest conservation for global warming emissions credits

mongabay.com

December 4, 2006

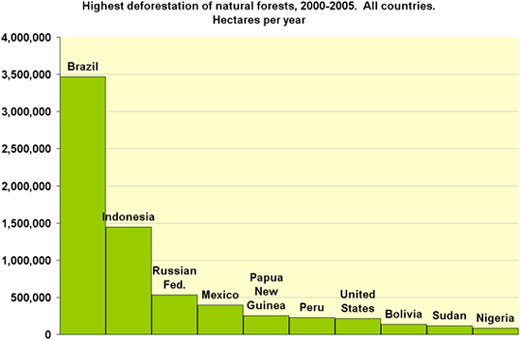

Tropical deforestation is one of the largest sources of human-produced greenhouse gases yet it has no place in existing climate agreements. This has been a point of contention in negotiations as the United States has objected to some developing countries — notably Brazil and Indonesia — to be getting an apparent “free ride” on deforestation-related emissions in addition to emissions from fossil fuel sources.

Recent negotiations have looked at this issue from a different perspective, one where developing countries would be paid by industrialized countries for reducing their deforestation rates. Globally the payoff could be immense, extending well beyond helping mitigate global warming emissions to safeguard biodiversity and important ecological services. Leading scientists have called such plans a “win-win” scenario for all parties and even the World Bank and U.N. have voiced support for the concept.

So how would it work?

Tropical forests play an important role in the global carbon cycle, locking up atmospheric carbon in their vegetation via photosynthesis. The vegetation and soils of the world’s forests contain about 125 percent of the carbon found in the atmosphere. When forests are burned, degraded, or cleared, the opposite effect occurs: large amounts of carbon are released into the atmosphere as carbon dioxide along with other greenhouse gases (nitrous oxide, methane, and other nitrogen oxides). The burning and conversion of some 13 million hectares of forests per year releases more than two billion metric tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, or about 20 percent of anthropogenic emissions of carbon dioxide and 25 percent of total greenhouse gas emissions. Reducing this source of heat-trapping gas emissions could do a lot in the fight against climate change.

|

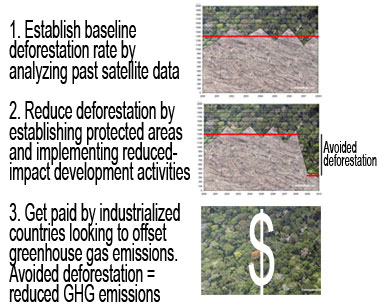

Under a proposal put forth by a coalition of developing countries last year, tropical forest countries would agree to set aside forest land that would otherwise be cleared in exchange for payment from industrialized countries looking to reduce their carbon emissions in order to meet targets set under international agreements like the Kyoto Protocol.

“Avoided deforestation funds could be used for all policies and measures aimed at lowering deforestation rates, including the establishment of protected areas, controlling illegal logging and land-use conversions, poverty alleviation initiatives and improvements in governance while at the same time reducing the overall cost of mitigating climate change,” said Johannes Ebeling, a Masters of Environmental Science student at Oxford University who just completed an analysis of the potential of carbon finance to reduce emissions and preserve forests. In his working paper “Tropical deforestation and climate change: Towards an international mitigation strategy” [PDF], Ebeling argues that incorporating “avoided deforestation” into an international climate agreement would “lower global mitigation costs” and “allow countries to reach more ambitious reduction targets at little or no extra cost.” Ebeling says that avoided deforestation might “also pave the way for including more countries and stakeholders into international mitigation efforts,” something which has been a sticking point in climate negotiations.

What’s avoided deforestation worth?

Potential value of avoided deforestation under a scenario where deforestation rates are reduced 20 percent and global carbon is valued at 55 /tC ( 15 /tCO2). While $4.3 billion may seem like a trifling amount for Brazil, it exceeds the amount of money currently allocated yearly to forest protection efforts. |

In his paper, Ebeling calculates the potential value of avoided deforestation under various scenarios for ten tropical forest countries — Bolivia, Brazil, Democratic Republic of Congo, Gabon, Indonesia, Mexico, Papua New Guinea, Peru, Sudan, and Thailand — that hold, and are responsible for the deforestation of, roughly sixty percent of the world’s remaining tropical forests. Assuming a 10 percent reduction of deforestation, avoided deforestation compensation could be $2-12.1 billion (1.5-9.1 billion Euros) depending on the market rate of carbon (5-30 euro per ton of carbon dioxide). Under more ambitious cuts, under which deforestation rates would be halved, the sample of ten tropical countries could see their fortunes rise from $10.1-60.7 billion (7.6-45.5 billion euros) per year. Globally, the dollar value of halving tropical deforestation could top $103 billion per year in compensation for qualifying countries. The plan would offer further ancillary benefits from forest conservation says Ebeling, who attended the November 2006 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in Nairobi.

“Considering the enormous co-benefits of reducing tropical deforestation — protecting global biodiversity, conserving soil and water resources, and improving rural livelihoods — providing carbon finance for avoided deforestation seems like an excellent investment for the international community,” he said.

While Ebeling concedes there are still some hurdles to overcome, such as concerns over sovereignty and establishing a baseline of historical deforestation against which to measure reduction in deforestation rates, he is optimistic avoided deforestation could well become part of an international climate agreement by 2012. He says that political as well as popular momentum are driving interest in the proposal and that even Brazil, which somewhat counter-intuitively had resisted such proposals, is pushing elements of the tropical forest conservation compensation idea.

“The political debate gained new momentum in late 2005 when a proposal submitted to the UNFCCC by Papua New Guinea and Costa Rica on behalf of the recently formed “Coalition for Rainforest Nations” called for the inclusion of [avoided deforestation] into future climate regimes,” wrote Ebeling. “The proposal suggests creating a mechanism of compensation for countries which reduce their deforestation rates and thus their GHG emissions. It differs from previous approaches in that it recommends measuring deforestation prevention on a national level against a historical baseline, rather than focusing on individual forest conservation projects.”

“I am actually quite optimistic with respect to negotiations on climate change and other environmental agreements. Climate change and especially the role of deforestation are relatively recent issues on most countries’ political agenda and they are linked to difficult questions and decisions about economic development and national sovereignty,” he said. “But no matter how sensitive these questions are, they need to be addressed and I sincerely hope that the discussion about avoided deforestation can re-invigorate the global debate about a truly sustainable development. Including avoided deforestation into international climate change mitigation strategies by providing carbon financing to tropical countries provides a unique opportunity to bridge the notorious gap between global (climate) benefits and local (opportunity) costs.”

In early December 2006, Ebeling elaborated on his carbon finance research, fielding some questions from mongabay.com.

Mongabay: In your paper you mention that Brazil is one of the few parties that has expressed some form of opposition to including avoided deforestation in future agreements. The press reported that Brazil planned to offer some avoided deforestation plan in Nairobi. Did this happen? What are the main points of the Brazilian initiative if one was indeed proposed by the Brazilian delegation?

Ebeling: The position of Brazil is indeed quite interesting and has created much discussion over the last year, considering that emissions related to deforestation in Brazil are higher than in any other country and indeed make it one of the world’s top emitters of greenhouse gases. The government’s opposition to the Reducing Emissions from Deforestation (REDD) proposal is surprising to many because the country stands to gain the lion’s share of compensation payments for reducing deforestation and even more so given Brazil’s demonstrated efforts and abilities to control deforestation in the Amazon.

It appears that environmentally-minded groups within the Brazilian government and society are gaining ground and may be moving the country towards accepting the proposal put forward in Montreal last year, at least in a modified version. The proposal made by Brazil during the United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP) is a strong indication of this. There are still no official documents outlining the approach but the idea is to set up an international trust fund which would compensate countries for their efforts to reduce emissions from deforestation. The fund would draw upon voluntary contributions from governments of industrialised countries and payments would be based on quantified emission reductions, calculated against a historic reference scenario of a country’s emissions.

When one takes the main elements of this proposal, it is actually surprisingly similar to the main other scheme in the race: using carbon markets and tradable emission credits to compensate governments for verified emission reductions. This is impressive and encouraging, considering that Brazil was opposed to even quantifying emission reductions from deforestation at a national level only half a year ago. I do not see realistic chances for a major additional international fund to be established and personally expect that Brazil will have to reconsider its current rejection of carbon trading approaches.

Mongabay: From your interviews, did you get a sense of inevitability with regard to the inclusion of some form of avoided deforestation agreement being put in place by 2012? Are the potential “deal-breakers” likely to be overcome by then?

Ebeling hiking in not-so-forested landscapes of Wales. |

Ebeling: At this stage, everything is still possible, including a complete failure of the initiative to reduce emissions from deforestation through an international agreement. In fact, if countries do not agree on an approach within the next few years, e.g. because they get caught up in detailed technical discussions, I think the issue might very well lose the necessary political momentum. However, judging from my interviews and conversations with delegates in Nairobi, many organisations and governments have invested significant amounts of energy and resources into promoting and exploring the proposals and will be unlikely to now simply drop the issue. The issue of deforestation and climate change has also received a lot of media coverage in recent months and now seems well established both on the international agenda and in public awareness.

Some of the major potential deal-breakers I identified still remain and have to be resolved. Among else, there is the question of how much money individual countries could potentially earn through carbon finance and that depends directly on how much they have deforested (and hence emitted) in the past and if that trend can be projected into the future. More and more countries have made it clear that they want to receive rewards for past conservation actions, e.g. Costa Rica, and also for increases in forest cover, e.g. India. Of course this raises concerns about the integrity and “additionality” of carbon credits because such rewards may not reflect actual, additional emission reductions. Environmental NGOs will almost certainly oppose the creation of “hot air”.

Another potential deal-breaker is the big question of longer-term emission targets for developing countries (after the first commitment period of the Kyoto Protocol ends in 2012). Developing countries do not have quantified emission reduction commitments under the current agreement and many governments are extremely careful to endorse any schemes that could resemble such commitments. Some are concerned that approaches which begin as “voluntary”, such as the avoided deforestation proposal, may later pave the way for non-voluntary emission caps. Brazil, but also China, India, and Mexico, in principle are prime candidates for future emission targets given their projected economic growth and the associated rise in emissions. After all, the discussion about avoided deforestation is not just about forests but also about the future of the whole climate change regime. It is, in fact, about the question of what the phrase “common but differentiated responsibilities” (UNFCCC) means in practice.

Mongabay: Do you expect that an avoided deforestation agreement would be sophisticated enough to include provisions on forest “degradation” versus “deforestation”? Logging and some other activities don’t show up as “deforestation”, though they have been shown to reduce carbon storing capabilities of forest. Will an agreement likely account for this?

Ebeling: Forest degradation, as opposed to outright deforestation, is indeed one of the complicated technical issues with implications for the design and effectiveness of a political agreement. Selective logging has been shown to significantly degrade forests — without reducing the forest cover below certain thresholds which are used to define “deforestation”. Obviously, a lot of carbon can be emitted by removing trees and damaging forests before the commonly used threshold of 10 percent crown cover is crossed.

One option is to wait for the development of sophisticated global satellite systems which could detect and quantify all such changes in a forest’s carbon content. However, this may take many years and delay effective action by time we do not have. The alternative is to use pragmatic approaches to account for the reduced carbon content of degraded forests. For example, there are ideas to simply discount the carbon storage value of forests which show signs of human intervention — detectable with today’s satellite systems — by a certain amount, e.g. 50 percent. This would produce conservative estimate, meaning we would be on the safe side when paying for climate benefits; it would be cheap and would allow us to start international schemes quickly.

I could very well see negotiators to agree on such pragmatic and effective solutions. We also have to remember that measuring industrial emissions of most greenhouse gases in industrialised countries was fraught with similar or much greater uncertainties when the original Kyoto Protocol was signed in 1998. It has since become clear that the effectiveness of climate change mitigation does not depend so much on scientific and measurement certainty but on political will, ambitious reduction targets, and effective rules of international agreements.

Highest deforestation of natural forests, 2000-2005. All countries. Credits: R. Butler |

Mongabay: In terms of determining baseline deforestation, what can be done in cases where data is truly insufficient to measure prior deforestation? Might re-analysis of archived aerial imagery and remote sensing data come to the rescue?

Ebeling: The scientific remote-sensing community pretty much agrees that we have all the necessary raw data on a global level. It may not be readily accessible but could be made available relatively rapidly and at reasonable cost by processing existing satellite imagery. Several organisations are currently working on this and are making good progress. There may be a need for additional start-up financing but this is small compared to the cost of launching new satellites and minuscule compared to the costs of inaction on the issue. Overall, such technical and information barriers can be overcome given sufficient political will. Obviously, existing uncertainties are highlighted and exaggerated by a small group of those who want to prevent an effective agreement, much like during the general discussion about climate change.

Mongabay: What are the key benefits of including avoided deforestation in future climate agreements?

Ebeling: In view of the imminent danger of catastrophic climate change and the obvious difficulty of most countries to achieve sufficient reductions in greenhouse gas emissions, it seems imperative to include all major sources of emissions and emitters in forthcoming international climate regimes. The world cannot afford to ignore an emission source as large as tropical deforestation. Given this need, all the raised concerns dwindle in importance and certainly do not justify running a much larger risk, namely unabated planetary climate change. Moreover, my analysis shows that including avoided deforestation into an international climate regime would definitely lower global mitigation costs. Even more important, it would allow countries to reach more ambitious reduction targets at little or no extra cost. It might also pave the way for including more countries and stakeholders into international mitigation efforts.

Considering the enormous co-benefits of reducing tropical deforestation — protecting global biodiversity, conserving soil and water resources, and improving rural livelihoods — providing carbon finance for avoided deforestation seems like an excellent investment for the international community.

Mongabay: Did you see much progress on avoided deforestation in Nairobi?

Clear-cutting of rainforest in Peru. Photo: Rhett A. Butler |

Ebeling: The official mandate for this COP was narrowly restricted to a 2-year process, agreed last year in Montreal, in which countries would define the scope for an expert workshop on the issue in March 2007. A first one took place in earlier this year in Rome. Delegates agreed to focus mainly on policy approaches during this next workshop.

At a first glance, this seems like a very humble or even insignificant outcome. However, compared to previous meetings, the negotiation climate was very constructive and delegates did not become distracted by calls from certain countries to merely discuss scientific and technical issues. Informal negotiations were very active and focused mainly on resolving differences between major stakeholders, namely PNG and the Rainforest Coalition on the one side and Brazil on the other, but also including several Latin American countries and India.

No one could expect giant leaps in the discussion or concrete agreements to emerge from this meeting and I do not share the pessimistic coverage of the conference by some media. After all, progress on avoided deforestation is dependent on what happens in the larger picture of post-2012 talks. Political negotiations, especially on the international level, are almost always slow and have to consider a multitude of interlinked issues. Considering the overall history of international cooperation, I am actually quite optimistic with respect to negotiations on climate change and other environmental agreements. Climate change and especially the role of deforestation are relatively recent issues on most countries’ political agenda and they are linked to difficult questions and decisions about economic development and national sovereignty.

About Johannes Ebeling

Johannes Ebeling works as a consultant for EcoSecurities, a Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) project developer, carbon trader, and environmental finance consultancy. His main areas of expertise are project design and policy advice for linking climate change mitigation with biodiversity conservation. Before joining EcoSecurities, Johannes worked on tropical forest certification with the GTZ and on energy policy design with the Oeko Institut in Germany. He has a background in Political Science, Biology, Geography, and Environmental Management.

Ebeling’s paper appears at “Tropical deforestation and climate change: Towards an international mitigation strategy”