Global warming could make Arctic sea ice-free by 2040

Global warming could make Arctic sea ice-free by 2040

mongabay.com

December 11, 2006

Global warming is causing an abrupt retreat in Arctic sea ice that could leave the Arctic Ocean with ice-free summers by 2040 according to research published in the December 12 issue of Geophysical Research Letters.

A team of scientists from the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR), the University of Washington, and McGill University used computer modeling to forecast the impact of greenhouse gas emissions on the Arctic. The models indicated that “the extent of sea ice each September could be reduced so abruptly that, within about 20 years, it may begin retreating four times faster than at any time in the observed record,” according to a statement from NCAR.

“We have already witnessed major losses in sea ice, but our research suggests that the decrease over the next few decades could be far more dramatic than anything that has happened so far,” said NCAR scientist Marika Holland, the study’s lead author. “These changes are surprisingly rapid.”

In one model simulation which assumed that greenhouse gases continue to build up in the atmosphere at the current rate, September ice coverage shrinks from 2.3 million to 770,000 square miles in a 10-year period, and nearly disappears by 2040. The model also shows that winter ice thins from 12 feet think to less than 3 feet.

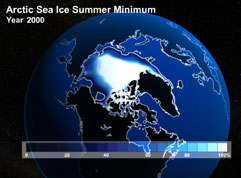

The image from 2000, based on simulations produced by the Community Climate System Model, shows the approximate extent of Arctic sea ice in September. The model indicates the extent of this late-summer ice could begin to retreat abruptly within several decades (top). By about 2040, the Arctic may be nearly devoid of sea ice during the late summer unless greenhouse gas emissions are significantly curtailed (bottom). Courtesy of UCAR. |

The researchers say that reduction of sea ice will result from changes in ocean currents, which are expected to bring warmer waters to the Arctic, and the changes in the reflectively of the Arctic Ocean. Since open water absorbs more sunlight than does ice, disappearing sea ice will accelerate warming in the region.

“As the ice retreats, the ocean transports more heat to the Arctic and the open water absorbs more sunlight, further accelerating the rate of warming and leading to the loss of more ice,” Holland explained. “This is a positive feedback loop with dramatic implications for the entire Arctic region.”

The scientists said that slowing greenhouse gas emissions could reduce the loss of Arctic sea ice.

“Our research indicates that society can still minimize the impacts on Arctic ice,” noted Holland.

The new research builds on recent studies showing a rapid decline in Arctic sea ice. In October researchers from the University of Colorado at Boulder reported that sea ice is declining at about 8.6 percent per decade, or at about 23 million square miles per year. They noted the formation of a large area of open water — called a polynya — north of Alaska during the 2006 season. The ice-free area was larger in area than Britain and theoretically would have allowed a ship to pass from Northern Siberia to the North Pole without much difficulty. At the time the researchers said no one knew was triggered the formation of the polynya but warming temperatures and thinning sea ice could make them more common in the future. A related NASA-funded study in September found that perennial sea ice, which remains year-round, shrank by 14 percent or 730,000 square kilometers [280,000 square miles] — an area the size of Texas — between 2004 and 2005. The researchers say that perennial sea ice was replaced with seasonal ice, which is more vulnerable to summer melt.

Other scientists have warned the continuing decline in winter ice could be detrimental to marine animals, including polar bear and the walrus. A second NASA study, also published late this summer, said that the disappearance of polar bears is limiting their ability to hunt and could be responsible for an observed decline average weight of adult bears and increased infant mortality rates.

This article uses quotes and information from an NCAR news release and previous mongabay.com articles.