Meanwhile, Colorado, Mississippi basins are storing more water

New satellite data from NASA show that the Mississippi and Colorado River basins are storing more water over the past five years, while the Congo, Zambezi and Nile basins are drying. While the findings are good news for U.S. agriculture, the research indicates that Africa continues to face geographic hardship.

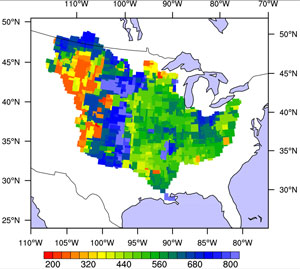

The NASA research, presented today at the American Geophysical Union meeting in San Francisco, is based on analysis of data from two Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (Grace) satellites which monitor small “month-to-month changes in Earth’s gravity field that are primarily caused by the movement of water in Earth’s land, ocean, ice and atmosphere reservoirs. Using this data, NASA scientists can estimate seasonal water storage variations in rivers, lakes and underground aquifers as well as the amount of water discharged by freshwater streams and rivers. Until now these measurements have been poorly monitored.

“Grace is providing a first-ever look at the distribution of freshwater storage on the continents,” said Dr. Jay Famiglietti, professor of Earth System Science at the University of California, Irvine. “With longer time series, we can distinguish long-term trends from natural seasonal variations and track how water availability responds to natural climate variations and climate change.”

Some climate models have predicted that global warming will cause parts of Africa to dry, potentially worsening agricultural conditions. The new Grace data seem to confirm, at least over the past five years, that this may be occurring in some basins that provide water for millions.

“Several African basins, such as the Congo, Zambezi and Nile, show significant drying over the past five years,” reported a statement from NASA.

NASA says hydrologists can use the data to “identify possible trends in precipitation changes, groundwater depletion and snow and glacier melt rates, and to understand their underlying causes” — information crucial for managing water resources, especially in vulnerable parts of Africa and Asia, where water scarcity puts agriculture and public health at risk.

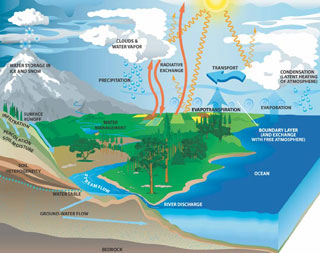

When merged with computer models, Grace water storage data can be used for water resources and agricultural applications. Image credit: NASA/JPL |

“Grace data improve our understanding of the water cycle and simulations of soil moisture, snow and groundwater in computer models,” said Dr. Matt Rodell, a hydrologist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. “This is a key step toward better weather, stream flow, flood, drought and water resource forecasts worldwide.”

“Grace detects water storage changes from Earth’s surface to its deepest aquifers. Water can’t hide from it,” said Dr. Michael Watkins, Grace project scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California.

“Remote sensing of groundwater has been a Holy Grail for hydrologists because it is stored beneath the surface and is not detected by most sensors,” said Famiglietti. “Outside of the United States and a few other developed nations, it is not well monitored. It’s been speculated that many of Earth’s key aquifers are being depleted due to over-exploitation, but a lack of data has hampered efforts to quantify how aquifer levels are changing and take the steps necessary to avoid depleting them. With additional data, such as measurements of surface water and soil moisture, we can use Grace to solve this problem.”

This article is based on a news release from NASA.