Mexico’s rainforests depend on government conservation efforts

An interview with Dr. Alejandro Estrada,

senior research scientist at Los Tuxtlas:

Mexico’s rainforests depend on government conservation efforts

Rhett A. Butler, mongabay.com

November 21, 2006

Few people realize that Mexico is home to the northernmost extent of rainforests that once extended clear down to the Amazon Basin.

Though diminished in extent to about 30 percent of their original range, these rainforests are still characterized by high levels of biodiversity, including such charismatic species as jaguar, howler and spider monkeys, and macaws. These forests are also inhabited by indigenous groups who live in ways largely unchanged since the arrival of Columbus in the 15th century.

While still threatened by encroachment and illegal activities, in recent years the Mexican government and an assortment of environmental organizations has made progress in protecting these forests. Particularly active in these conservation efforts is the Los Tuxtlas Biological Station (Estación de Biología Tropical Los Tuxtlas del Instituto de Biología Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México) based in Veracruz (southern Mexico). In November 2006, Dr. Alejandro Estrada, senior research scientist at Los Tuxtlas (www.primatesmx.com) and a leading authority on these forests, answered some questions on Mexico’s remaining rainforests and conservation efforts in the country.

Mongabay: How did you decide to pursue primate research in the state of Veracruz?

Dr. Alejandro Estrada. |

Estrada: As a youngster who spent a lot of time visiting the primate section of the Mexico City zoo, I developed a lifetime ambition to become a primatologist. To achieve this I planned to train myself abroad in primate studies, return to my country of birth and start a series of studies with the little known primate species and populations that existed in the tropical rain forests of southern Mexico.

When completing my Ph.D at Rutgers University. I was fortunate enough to be hired as a research scientist by the University of Mexico. This gave me the opportunity to discover the existence of the field station for tropical biology Los Tuxtlas, located in southern Veracruz (this field station is part of the research infrastructure of the Institute of Biology of the University of Mexico). In my first trip to the field station, I not only encountered a magnificent rainforest, but also its conspicuous and vocal arboreal primates: the howler and spider monkeys. And then, my decision was made. Los Tuxtlas in southern Veracruz would become my base of operations from where I could turn my vision of dedicating my life to the study of wild primates into reality.

Mongabay: How are rainforests in southern Mexico different from Belize and other parts of Latin America?

Estrada: The tropical rainforests of southern Mexico are the northernmost representation in the American continent of the Amazonian rainforests. Practically all plants and animals present found in these diverse forests have their origin in the Amazon basin. Such biological richness is shared by southern Mexico with the lowland rainforests of Belize and Guatemala. All together, these three areas of rainforest constitute the largest landmass of tropical rainforests found today in Mesoamerica. Because these forests are found not too distant from the United States and Canada, they are also home to millions of migratory birds that use the forests as wintering grounds or as stopovers when migrating from northern to southern and warmer habitats. It is estimated that between 20-30% of the diversity of bird species found in the tropical rainforests of southern Mexico is represented by song birds from the United States, Canada and Alaska that spend the winter months in these rainforests. Hence, the relevance of these rainforests for the conservation of wildlife transcends the regions in which they are found in southern Mexico.

Mongabay: Are the forests of Los Tuxtlas, Veracruz well protected? Are there threats on the horizon? Is hunting an issue in the area?

Lake in Los Tuxtlas. Photo courtesy of Dr. Alejandro Estrada. |

Estrada: The tropical rain forests of Los Tuxtlas, like those of the rest of southern Mexico have fallen victim to pressures derived from human activity, mainly aimed at converting the rainforests to pasturelands and to other types of agricultural fields. The Los Tuxtlas region has been severely transformed by human activity in the last 50 or so years, with the result that currently, only about 20-30% of the forest originally present (2,500 km2) remains today.

Between the 1960s and early 1990s, high deforestation rates threatened the integrity of the rainforest protected by the University of Mexico. However the situation has changed since then. Public and government concerns over protection of these rainforests, coupled with the national and international scientific impact of Los Tuxtlas, resulted in about 70% of the region being declared as the Los Tuxtlas biosphere reserve. This action produced a decline in deforestation and led to the incorporation of rural communities into conservation and restoration projects.

Currently, the Los Tuxtlas field station (700 ha) is embedded into close to 15,000 ha of protected pristine rainforest. This status ensures the integrity of its flora and fauna and the possibility of continuing the long-term investigations on the plants and the animals, including the primates, that exist in these rainforests. While hunting and illegal trafficking were important added pressures upon wildlife in those decades of extensive loss of forest cover in the region [19060s-early 1990s], today these are almost non existent.

However, in spite of these achievements to preserve the remaining rainforests of Los Tuxtlas, massive local extinctions of plants and animals has taken place in those areas where human presence and activity was and still is strongest. As a result, large areas of rainforest needs to be restored along with the implementation of other conservation projects to ensure the ongoing survival of wildlife species that have a restricted distribution within the region.

Mongabay: How well are primates adjusting to degraded forests and agricultural landscapes? Are there conflicts between landowners and howler monkeys?

Young spider monkey (Ateles geoffroyi yucatanensis) (top). Howler monkey (Alouatta pigra) (Lower two images). Courtesy of Dr. Alejandro Estrada. |

Estrada: Howler and spider monkeys of southern Mexico have not escaped the impact of human activity upon their habitats. It is estimated that the original distribution of tropical rainforests in southern Mexico has been reduced to about 30%. This has resulted in the local extinction of populations of howler and spider monkeys in many parts of southern Mexico. Because spider monkeys have large area requirements to sustain themselves as a result of their fruit-eating habits, they have usually been the first to disappear when the forest is cut. Howler monkeys have been able to persist for many years in small and isolated habitats thanks to their ability to use leaves as a food, which are a more predictable food source than fruit. However, populations of these two primates living in human modified landscapes exist under sub optimal ecological and demographic conditions that has weakened the odds of their long-term survival.

While these issues have been of concern in our primate conservation research, the possibility that some agricultural practices may favor the persistence of primate populations in human modified landscapes is an intriguing issue. Our approach here has been to move away from the usual binary view of conservation in which conservation is viewed as a conflict between agricultural practices and the need to preserve nature, and to consider an approach in which agricultural activities may also be a tool for the conservation of primates in human modified landscapes. The primates and other fauna that exist in agricultural landscapes are important components of the local biodiversity and their presence and conservation in these anthropogenic environment merits attention and study. Our research has shown that several agroecosystems, especially those arboreal in nature and/or growing under the shade of remnant forest or of trees planted by humans (e.g. coffee, cacao, etc), are capable of sustaining howler and spider monkeys, as well as other mammals and many bird species for many years. In some cases these agroecosystems function as stepping stones or ecosystem corridors allowing movements of individuals across the landscape thus between populations originally isolated by fragmentation of their habitat. Our studies indicate that in the majority of the cases landowners tolerate the presence of the monkeys in the agroecosystems, as both howler and spider do not become pests to economically important crops such as coffee and cacao plants.

Mongabay: The U.N. reports that Mexico loses more than 250,000 hectares of forest per year. Where is this loss occurring? Is the government taking steps to reduce forest clearing? Does it have much control over illegal logging, poaching, and clearing for agriculture? Is the situation getting better or worse?

Estrada: Southern Mexico along with Honduras and Costa Rica are have relatively low deforestation rates for Mesoamerica (southern Mexico about -1.1%/yr). Much of the loss is taking place in all of the seven states of southern Mexico, with much of the forested land being converted to pasture lands and other types of agricultural fields. High population growth rate (3%/yr) coupled with high poverty rates and low human development among the inhabitants of southern Mexico has led the government to open up large areas of pristine rainforest for colonization as a poverty alleviation solution. This, plus local and global market demands for beef and other agricultural products, has produced dramatic changes in the original forested landscapes, altering its original distribution and that of the primate populations and species.

Illegal logging, poaching, and clearing for agriculture are still common, especially in remote areas of southern Mexico where supervision is inadequate by the Mexican environmental agencies. In more accessible areas, supervision has resulted in significant decreases in illegal logging, poaching and clearing for agriculture, and rural and indigenous communities are oriented toward preserving segments of their forested lands as community reserves.

The future of unprotected forests in southern Mexico is however uncertain. High population growth rates are projected for the next 30 or so years for southern Mexico. This, and extreme poverty and underdevelopment are important issues that need to be resolved by the local, state, and federal governments.

Mongabay: Is corruption an issue in conservation efforts in southern Mexico?

Estrada: Corruption is an important issue in conservation efforts in southern Mexico. Illegal logging, trafficking, hunting and other activities that impact the well being of rainforests in various ways are favored by this problem. There is still much that needs to be done along this line, including transparency in administrative steps and the rightful implementation of the Mexican legislation that protects wildlife.

Mongabay: How did the political situation in Chiapas during the late 1990s affect the forest and conservation efforts?

Lacandon reserve near Metzabok village. Courtesy of Dr. Alejandro Estrada. |

Estrada: Indigenous unrest in Chiapas over the last 10 years was the result of the desire by the local rural inhabitants to improve their living conditions. This included the redistribution of land – large landholdings were in the hands of a few cattle ranchers — to benefit many rural inhabitants belonging to several Maya indigenous groups. Areas of tropical rainforests were cleared with the new assignation of land and illegal settlements also sprouted in many forested areas, leading to additional clearing and disturbance. The government has tried to resolve these issues with moderate success.

On the positive side the political situation in Chiapas raised public awareness about the social plight of local rural inhabitants and also about the need to protect the tropical rainforests where these people live, as well as those already protected because they had been designated as Natural Protected Areas. Unfortunately, attempts to improve living conditions of local people has also meant building access roads and other infrastructure resulting in pressures upon once isolated rainforest areas in the state.

Mongabay: Has oil exploration and development had an impact on forest areas in southern Mexico?

Estrada: Oil exploration and development in southern Mexico has severely impacted the rainforests in the lowlands of the state of Tabasco, segments of coastal Campeche in the Yucatan peninsula, and areas in southern Chiapas. In these cases, large area of tropical rainforests have been converted into oil exploration fields with numerous access roads crisscrossing the land, and where pollution is an ever present problem. Because oil production is a major economic activity in Mexico, it is difficult to shift the trend. However, some efforts at conducting environmentally friendly oil exploration and development have been undertane recently by Pemex, the government-based oil production company in Mexico.

Mongabay: Is the Los Tuxtlas field station actively involved in conservation efforts?

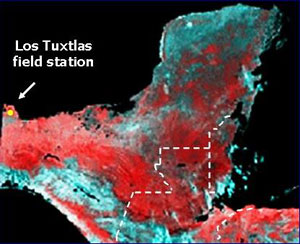

The location of Los Tuxtlas field station in Mexico. |

Estrada: The field station Los Tuxtlas, founded in 1967, has a long history of conservation efforts in the region of the same name in southern Veracruz. While its focus of activities is basic tropical rain forest research, resources and others have been channeled over several decades to disseminate information about the importance of the tropical rainforest among the local communities and municipal governments. These efforts led to the delimitation of a small sector of tropical rainforest in the university property as an educational zone where every year thousands of local primary, mid-level and higher level school students are received and provided with guided visits. Orientation talks are continuously given by university students and research staff working at the field station to local schools, and more recently, rainforest restoration projects have been developed with local communities, whose members are planting thousands of useful rainforest trees.

The Los Tuxtlas field station was a major catalytic component in promoting the creation of the biosphere reserve Los Tuxtlas around 12 years or so ago by the federal government. The station is a current member of the board of institutions coordinating the management and development of the reserve, with the central philosophy of involving the local and rural populations in its protection.

Finally, it is important to note that the Los Tuxtlas field station is one of a handful of field stations around the tropical world (e.g. the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute field stations) where an orderly accumulation of knowledge about the rainforest ecosystems has been taking place for decades. Such basic information (inventories, ecological studies, etc) represent the data banks on tropical rainforests throughout the world, and constitute the empirical and conceptual tools that we can use in proposing conservation solutions.

Mongabay: What are the most important steps to protecting Mexico’s biodiversity and tropical forests?

Lacandon Indian reserve. Courtesy of Dr. Alejandro Estrada.

|

Estrada: In spite of the social and economic problems faced by Mexico, and especially those of the south where the indigenous component of the human population is very important, the Mexican government has taken up some initiatives to preserve native ecosystems, including the rainforests. Such initiatives involve the ratification of the International Convention on Biological Diversity — Mexico was the first Mesoamerican country to sign the convention in 1993. This was followed by the creation of a system of Natural Protected Areas (NPAs) in southern Mexico as biosphere reserves, ecological and community reserves, national parks and others (about 15% of the territory of southern Mexico — is under some kind of protection). However, lack of enough resources mean that several of these NPAs are more like paper parks while others are becoming virtual islands of vegetation as a result of high deforestation rates in surrounding areas. There are problems with illegal squatters and settlements through forest parks and reserves.

More recently, Mexico has begun to actively participate, in conjunction with the rest of Mesoamerican countries, in the establishment of the Mesoamerican Biological Corridor project. The cardinal principles of this unique project are to avoid isolation and fragmentation of NPAs by establishing a series of corridors that will connect protected rainforests to allow movement of resident wildlife, and to promote sustainable use of biodiversity and the land in intermediate areas.

Finally, support of smaller projects such as that of the Los Tuxtlas field station of the University of Mexico by the Mexican government demonstrates that, in spite of underdevelopment, tropical countries can successfully conserve their rainforests as well as produce important scientific information.

Mongabay: Would the further development of tourism be beneficial to conservation efforts in the region or could it be detrimental by encouraging unregulated development?

Estrada: Because of the enormous attraction of the natural and cultural (e.g. the Maya civilization) Ecotourism is an activity being intensively promoted by the Mexican government in southern Mexico. The aim is to use the rainforests as generators of additional income for the local communities, and many small indigenous and non indigenous communities have or are developing projects. While a key rule has been to regulate development to protect natural resources, in some “hot spots” for tourism (e.g. the Caribbean coast — Cancun and the Mexican Rivera) this has not been the case.

Mongabay: What can people — both in Mexico and in the United States — do at home to help protect Mexico’s tropical forests?

A dry lake in Los Tuxtlas. Courtesy of Dr. Alejandro Estrada. |

Estrada: One way to protect Mexico´s tropical rainforests is to be aware that they are there. These forests are the northernmost representations of the Amazonian rainforest in the continent, and are the closest rainforests to the United States. They are critically important to preserve not only because of global concerns, but because they store huge natural resources so close to us. These rainforests are also the winter home of the majority of North American song birds, and they are inhabited by indigenous people who represent an important cultural component of North America. Visiting these rainforests and supporting local conservation efforts are two activities that can help raise more public awareness and ensure the long-term conservation of these magnificent ecosystems.

Mongabay: Do you have any advice for students, specifically in Mexico, wanting to pursue a career in primate research or conservation?

Estrada: Build up your passion for tropical rainforests by visiting the rainforest and by becoming involved in research and conservation activities in the tropics. You will not be disappointed. Everyday will be an act of discovery, as it has been for me for the last 30 years.

Links of interest

About Dr. Alejandro Estrada

Dr. Alejandro Estrada was born in Mexico City and is currently based at the field station Los Tuxtlas of the University of Mexico (UNAM) located in the Los Tuxtlas region of southern Veracruz. While Estrada was trained as a primate ethologist, his work has grown to encompass conservation and forest ecology.