Traditional customs pit young versus old in Indonesia’s Torajaland

Traditional customs pit young versus old in Indonesia’s Torajaland

Cultural Bankruptcy: Maintaining History at a Tremendous Cost in Sulawesi’s Torajaland

Tina Butler

October 19, 2006

The Torajanese people of Central Sulawesi, Indonesia, have long been renowned for their extravagant celebrations of the dead in funerals, graves, and effigies. Just outside of Rantepao, the regional capital of Torajaland, ostentatious and costly funerals take place often. But increasingly, such rites are dividing generations. As in other indigenous cultures around the world, a growing rift between the young and old is calling the foundations of tradition into question.

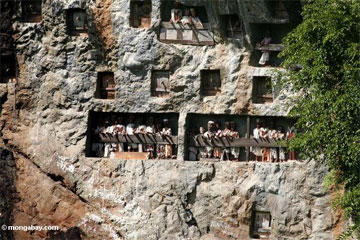

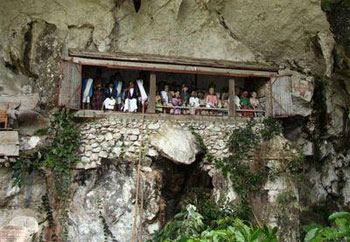

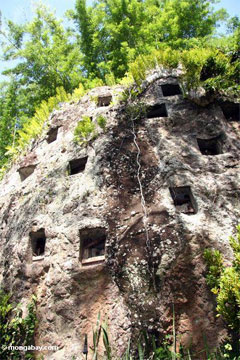

The Torajanese, or highland people, have maintained a cultural legacy that predates the introduction of Christianity through missionaries in the 1600s. For centuries, the people of Toraja have treated death with great ceremony, through dramatic rituals and elaborate funerals. The Torajanese entomb their dead in a variety of impressive if unlikely ways: in boulders, limestone cliff faces, hanging graves, caves and trees. Chambers are hand-chiseled out of the rock, a process that takes up to a year to complete and is particularly costly. Graves markings range from simple wooden doors to ornate tau taus, or carved wooden effigies. Babies are buried in the hollows of trees and their corpses are eventually subsumed by the living bark.

While maintaining cultural traditions is important to the Torajanese, the costs of their customary funerals are enormous. At the heart of the clash between the young and old of Toraja lies a grave economic problem. The funeral practices are so lavish and expensive that many families go deeply into debt to pay for the post-mortem celebration of a loved one. These debts are carried through generations, so that children are often born owing money for the funeral of a person they never knew and must spend their whole lives trying to pay back. Funerals breed impoverishment, but their social importance is so high that families will give up anything from a better house or farming equipment to higher education for their children—all to pay the cost of an appropriately profligate funeral.

Tombs carved in a rock face at Lembo [top], the slope-roofed houses of Palawa, a traditional village in Torajaland [bottom]. Graves cut out of boulders are called bori. Photos by Rhett Butler. |

Funerals cost so much that families avoid even acknowledging to their extended family and community that an individual has died until they can afford to have a proper funeral. In the village of Lembo, one woman is known to have shared her bedroom with her embalmed husband for almost two years with no funeral in sight. To family members residing on other islands, the report from the wife was that he was merely sick. Stories like these are not uncommon; in Toraja, people aren’t dead unless they have a funeral. Until then, they are only ill or sleeping.

WWhat makes funerals so expensive is largely the slaughter of animals and subsequent feast that are integral parts of any proper affair. The number of water buffalo slaughtered for funeral feasts is directly proportional to the wealth of the deceased’s family. At a funeral in 2004, one family’s request to slaughter more than 50 water buffaloes was turned down by the local government based on the rationale the almost the entire local population of water buffaloes would have to be killed, and that the community would not be able to replace the stock quickly enough. The well-to-do family compromised on 30 buffalo and nearly twice as many hogs. In an attempt to end the practice of excessive buffalo slaughtering, the Indonesian government has imposed a tax on each animal killed and also requires that one buffalo each be given to the tax collectors and local church. With buffaloes costing up to $400 each, these taxes make the practice even more prohibitive; however, the slaughter continues. The horns of buffaloes slaughtered at funerals are stacked outside ceremonial houses as a reminder of the event and reinforcement of the family’s wealth and status.

Funerals are not only an event for the family and community, but also for tourists. All funerals in Torajaland must be registered with the local government and then the tourist board, so that tour guides are kept aware of any funeral festivities tourists might see as they pass through. In this way, funerals bring in revenue for the local community, even while they continue to impoverish the local family hosts. When tourists attend these events, it is customary for them to bring a donation, almost always a carton of cigarettes, which does nothing to help the family or recoup their tremendous expenses.

Beyond the financial hardship, the environmental toll of the funerals is not insignificant, if highly regionalized. While renewable bamboo is increasingly used for temporary housing structures, threatened tropical hardwoods from Sulawesi’s fast-disappearing forests are felled for the tau taus and temporary ceremonial structures. The effigies endure, but it is believed to be bad luck to reuse platforms and housing erected for an earlier funeral, so there is significant waste. A shortage of local hardwoods mean that timber is even smuggled from neighboring islands, especially Borneo, worsening Indonesia’s already abysmal deforestation rate.

The generational conflict of the Torajanese in Sulawesi are part of a wider trend where traditions once seen as critical parts of a people’s culture are now viewed with scorn and contempt by younger generations for the hardship they create in places ranging from Makassar to Madagascar. While Westerns and tribal elders lament the loss of culture and disappearing languages — the U.N.estimates one language disappears every two weeks on average — sometimes there are more complicated forces underlying the transition.

“The government and tourists want us to continue our family traditions but sometimes the costs are just too high,” said Pahral, a villager near Lembo, through a translator. “We need to think more about education and the burdens on our children, and commit fewer resources toward our past ancestors.”

PHOTO JOURNAL

(more pictures)

|

Tau-Tau effigies at Londa Nanggala

Wooden effigies of the dead in cliff walls at Lembo

Wooden effigies of the dead at Lembo

Tradtional homes characteristic of Torajaland

Village elder drinking “tuak” alcohol out of a bamboo shoot. Poverty is an increasingly pervasive problem in Indonesia — more than 80 million of the country’s 246 million inhabitants live on less than a $1 per day. Photos by Rhett Butler. |