Forest fires result from government failure in Indonesia

Forest fires result from government failure in Indonesia

mongabay.com editorial

October 15, 2006

Indonesia is burning again. Smoke from fires set for land-clearing in South Kalimantan (Borneo) and Sumatra are causing pollution levels to climb in Singapore, Kuala Lumpur, and Bangkok, resulting in mounting haze-related health problems, traffic accidents, and associated economic costs. The country’s neighbors are again clamoring for action but ultimately the fires will burn until they are extinguished by seasonal rains in coming months.

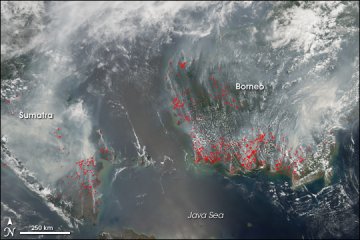

2006 fires in Borneo and Sumatra Smoke from agricultural and forest fires burning on Sumatra (left) and Borneo (right) in late September and early October 2006 blanketed a wide region with smoke that interrupted air and highway travel and pushed air quality to unhealthy levels. This image from the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA’s Aqua satellite on October 1, 2006, shows places where MODIS detected actively burning fires marked in red. Smoke spreads in a gray-white pall to the north. NASA image created by Jesse Allen, Earth Observatory, using data provided courtesy of the MODIS Rapid Response team. |

The fires — and their choking haze — have become a yearly occurrence in Indonesia. Some years are worse than others — especially when dry el Niño conditions turn the region’s forests into a tinderbox — but the overall trend is not encouraging. Why do these catastrophic fires continue to burn?

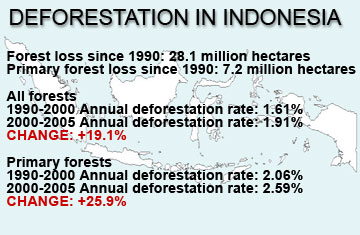

Fault should lie first with the Indonesian government for its systematic failure to enforce laws designed to reduce the country’s appalling rate of deforestation. Since 1990 official figures show Indonesia has lost a quarter of its forest cover. Loss of primary forests has been even worse: nearly 31 percent of the archipelago’s old growth forest have fallen to loggers and land developers over the same period. Menacingly, deforestation rates are not slowing. Annual forest loss has accelerated by 19 percent since the close of the 1990s, while yearly primary forest loss has expanded by 26 percent. These statistics should be an embarrassment to Indonesia and are testament to the government’s impotence in dealing with forest loss and incompetence in reigning in cronyism and corruption.

Forest loss in Indonesia

The direct causes of forest loss in Indonesia are not complex. Most deforestation is the result of logging and land conversion for agriculture. Today Indonesia is the world’s largest exporter of tropical timber — a commodity that generates upwards of US$5 billion annually — and the second largest producer of palm oil, one of the world’s most productive oil crops used in everything from cookies to biofuel.

Deforestation rates are climbing in Indonesia |

Legal timber harvesting affects 700,000-850,000 hectares of forest per year in Indonesia, but widespread illegal logging boosts the overall logged area to at least 1.2-1.4 million hectares and possibly much higher—in 2004, Environment Minister Nabiel Makarim said that 75 percent of logging in Indonesia is illegal. Despite an official ban on the export of raw logs from Indonesia, timber is regularly smuggled to Malaysia, Singapore, and other Asian countries. By some estimates, Indonesia is losing more than $1 billion a year in tax revenue from the illicit trade. Illegal cutting is also hurting legitimate timber-harvesting businesses by reducing the supply of logs available for processing, and undercutting international prices for wood and wood products.

Logging in Indonesia has opened some of the most remote, forbidding places on Earth to development. After decimating much of the forests in less remote locations, timber firms have stepped up operations on the island of Borneo and in provinces on New Guinea, where great swaths of forests have been cleared in recent years. For example, more 20 percent of Indonesia’s logging concessions are located in Indonesian Papua, up from 7 percent of in the 1990s.

Beyond logging, conversion of forest for large-scale agriculture, especially oil palm plantations, has been an important contributor to forest loss in Indonesia. The area of land covered by oil palm expanded from 600,000 hectares in 1985 to more than 5.3 million hectares by 2004. The government hopes to see this expanse nearly double within the next decade and, through its transmigration program, has encouraged farmers to turn wild forest lands into plantations. Since the fastest and cheapest way to clear new land for plantations is by burning, the effort has worsened fires: every year hundreds of thousands of acres hectares go up in smoke as developers and agriculturalists ignite the countryside before monsoon rains begin to fall in October or November.

Government failure

While Indonesia has laws to protect forests and limit agricultural burning, they are poorly enforced. Forest management in the country has long been plagued by corruption and lack of political commitment. Underpaid government officials combined with the prevalence of disreputable businessmen and shifty politicians, has traditionally meant that logging bans go unenforced, trafficking in endangered species is overlooked, environmental regulations are ignored, parks are used as timber farms, and fines and prison sentences never come to pass. Corruption, combined with an atmosphere of cronyism established under ex-president General Suharto, has at times directly undermined efforts to control forest fires: in 1997, the country was unable to use its special off-budget reforestation fund to help combat the fires because the money had been ear-marked for a failing car project owned by the dictator’s son. Today the government still refuses to effectively punish those who violate laws that ban fire-setting for land clearing.

It’s time for the Indonesian government to get serious about addressing deforestation and the recurrent fires. Political commitment is key — without it, vast sums of donor money will continue to be squandered without stemming illegal logging and forest loss.

The government needs to ratify the ASEAN Agreement on Transboundary Haze Pollution, a convention signed in 2002 following the 1997-1998 forest fires. The agreement calls for multi-national cooperation to combat fires in the region. Ratifying the agreement would be a first sign of political commitment to the issue, but the government would then need to be follow up with implementation and good governance initiatives, like enforcement of its relatively strict codes banning land burning. Without enforcement, laws are useless. Indonesia can no longer afford to overlook criminal activates by powerful interests. For example, it needs to follow up on Malaysia’s request to prosecute Malaysian companies involved in forest fires in South Kalimantan and Sumatra. Firms found to be responsible for illegal fire-setting, no matter where they are based, should see their business licenses revoked and their officers imprisoned.

As fires subside this winter, Indonesia should aggressively investigate opportunities afforded by the emergent carbon market which could allow the country to be compensated by protecting forests from development. Other innovative strategies — from comprehensive timber and agricultural certification to private sponsorship of forest conservation — should not be overlooked.

International failure

While it’s easy to lambaste the Indonesian government for inaction, the international community has also failed. Instead of criticizing Indonesia for its shortcomings, foreign governments should be pledging expertise and massive amounts of assistance. Indonesia’s forest fires have global impact by extinguishing biodiversity and contributing greenhouse gases to the atmosphere (the 1997 fires released an estimated 2.67 billion tons of carbon dioxide). Regionally, the fires poison the air and have even been linked to declining rainfall. In a case where Indonesia’s problems are the world’s problems, the global community needs to rise to the occasion to address these catastrophic fires in an intelligent and well-coordinated manner.

More on Indonesia’s fires

Borneo and Sumatra burn as forest fires rage — 10/4/2006

Forest fires are again buring across Borneo and Sumatra (Indonesia) according to satellite images released this week by NASA.

Forest clearing in forest area near oil palm plantations in Kalimantan Photo by R. Butler Vast areas of natural forest have been converted for soy farms in the Amazon and oil palm plantations in Asia. However, on a relative basis, oil palm may be more ecologically sound due to its higher oil yield than soy. In theory, because oil palm can produce as much as 30 times more oil per unit of area, it could require a lesser amount of land clearing. Of course planting oil palm on previously deforested land would be a preferrable option. At $400 per metric ton, or about $54 per barrel, palm oil is competitive with conventional oil. In the future, palm oil prices are expected to fall further as more oil palm comes under cultivation. |

|

Saving Orangutans in Borneo — 5/24/2006

A look at conservation efforts in Kalimantan, on the island of Borneo. I’m in Tanjung Puting National Park in southern Kalimantan on the island of Borneo. At 400,000 hectares (988,000 acres) Tanjung Puting is the largest protected expanse of coastal tropical heath and peat swamp forest in southeast Asia. It’s also one of the biggest remaining habitats for the critically endangered orangutan, the population of which has been great diminished in recent years due to habitat destruction and poaching. And orangutans have become the focus of a much wider effort to save Borneo’s natural environment. We are headed to Campy Leakey, named for the renowned Kenyan paleontologist Louis Leakey. Here lies the center of the Orangutan Research Conservation Project. Established by Birute Mary Galdikas, a preeminent primatologist and founder of the Orangutan Foundation International (OFI), the project seeks to support the conservation and understanding of the orangutan and its rain forest habitat while rehabilitating ex-captive individuals. The Orangutan Research Conservation Project is the public face of orangutan conservation in this part of Kalimantan, the Indonesia-controlled part of Borneo. Borneo, the third largest island in the world, was once home to some of the world’s most majestic, and forbidding forests. With swampy coastal areas fringed by mangrove forests and a mountainous interior, much of the terrain was virtually impassable and unexplored. Headhunters ruled the remote parts of the island until a century ago.

Shippers in Indonesia fight decree on illegal logging — 5/21/2006

According to a report from the International Tropical Timber Organization (ITTO), shippers in Indonesia are threatening to stop transporting logs if the government insists on enforcing a new decree on the transportation of illegal timber. The Indonesian National Ship-owners Association says that the Indonesian government’s proposal to impound ships carrying illegal timber would cause massive losses to the local shipping industry, according to the ITTO Tropical Timber Market Report. The association contends that authorities should only confiscate illegal wood, not the ships.

Why is palm oil replacing tropical rainforests? — 4/25/2006

In a word, economics, though deeper analysis of a proposal in Indonesia suggests that oil palm development might be a cover for something more lucrative: logging. Recently much has been made about the conversion of Asia’s biodiverse rainforests for oil-palm cultivation. Environmental organizations have warned that by eating foods that use palm oil as an ingredient, Western consumers are directly fueling the destruction of orangutan habitat and sensitive ecosystems. So, why is it that oil-palm plantations now cover millions of hectares across Malaysia, Indonesia, and Thailand? Why has oil palm become the world’s number one fruit crop, trouncing its nearest competitor, the humble banana? The answer lies in the crop’s unparalleled productivity. Simply put, oil palm is the most productive oil seed in the world. A single hectare of oil palm may yield 5,000 kilograms of crude oil, or nearly 6,000 liters of crude.

United States and Indonesia to fight illegal logging — 4/5/2006

The United States and Indonesia today agreed to fight illegal logging in some of the world’s most diverse rainforests. Indonesian Trade Minister Mari Elka Pangestu and Chief of the US Trade Office (USTR) Robert Portman said the two countries will coordinate efforts of protect Indonesia’s forests which have been significantly degraded and destroyed by the illicit timber trade. While Indonesia houses the most extensive rainforest cover in all of Asia, its natural forest area is rapidly being reduced by logging–most of which is illegal. Between 1990 and 2005 the country lost more than 28 million hectares of forest, including 21.7 million hectares of virgin forest, according to data from the United Nations.

Malaysia urges neighbors to help prevent haze — 9/27/2005

Malaysia urged its neighbours on Tuesday to ratify an agreement to control air pollution in southeast Asia, a month after forest fires in Indonesia caused some of the worst haze in the region in eight years.

Fires in peat lands cost climate — 9/6/2005

The tropical rainforests of Kalimantan have long been threatened and increasingly endangered by deforestation and other invasive types of human activity. However, a lesser known ecosystem in the region that is literally coming under fire, is the tropical peat lands, particularly in the central area of the province of Indonesian Borneo.

Forest fires have serious economic and health consequences warns FAO — 9/5/2005

Large forest fires in South-East Asia, notably in Indonesia, have caused serious health and environmental problems, in particular choking haze in the region, FAO said today.

Illegal loggers to be imprisoned in Malaysia, possibly executed in Indonesia — 8/30/2005

Illegal loggers will now face mandatory jail time in Malaysia under new laws expected to be implemented sometime early next year. Existing enforcement efforts, which rely on fines but are poorly enforced, have largely failed to curb illegal wood harvesting in the country’s tropical rainforests.