The science behind the movie “Snakes on a Plane” – how snakes see in the dark

The science behind the movie “Snakes on a Plane” – how snakes see in the dark

mongabay.com

August 7, 2006

Even in the dark, snakes on a plane could keep a close watch on passengers and crew thanks to small cavities near their snouts known as pit organs, according to a forthcoming article by Andreas B. Sichert, Paul Friedel, and J. Leo van Hemmen

published in Physical Review Letters.

American Physical Society news release:

Virtual Lens May Improve Heat Vision in Snakes

Even in the dark, snakes on a plane (at least those of the pit viper and boa varieties) could keep a close watch on terrorized passengers and crew thanks to small cavities near their snouts known as pit organs. The organs are sensitive to the infrared radiation emitted by warm prey such as rats, rabbits, and Samuel L. Jackson.

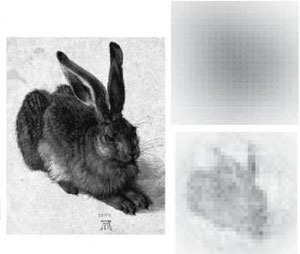

Snake IR View of a Rabbit |

An optical analysis of pit organs suggests that snakes shouldn’t be able to use the organ to track prey very well because the pit aperture is large and the organ is not very deep. However, studies have shown that snakes can localize heat sources to a surprisingly accurate resolution of five degrees (roughly the angular width of “Snakes on a Plane” costar Rachel Blanchard at three meters).

Physicists at the Technische Universität München believe the solution to the paradox could be a network of neurons in the snakes’ brains —a kind of snake brain firmware – that provides image enhancement as though the snakes were wearing virtual corrective lenses. Because snakes’ brains are small, the physicists kept their model of an image enhancing network simple. They discovered that even a crude network dramatically improves infrared imaging – which you might want to keep in mind if you ever book a flight on a snake-infested airline.

RELATED

Venomous snakes key to human evolution says new theory The ability to spot venomous snakes may have played a major role in the evolution of monkeys, apes and humans, according to a new hypothesis by Lynne Isbell, professor of anthropology at UC Davis. The work is published in the July issue of the Journal of Human Evolution.