Easter Island settled around 1200, later than originally believed

Rhett Butler, mongabay.com

March 13, 2006

New evidence suggests that colonization of Easter Island (Rapa Nui) took place later than originally believed. The research is published in this week’s issue of the journal Science.

Terry Hunt, an archaeologist with the University of Hawaii at Manoa, and a team of field researchers excavated archaeological deposits at the sand dunes of Anakena, the main canoe-landing spot on the island and found charcoal samples and rat-eaten palm nuts that dated to A.D. 1250. The discovery suggests that Easter Island was not settled until around the year 1200—400 to 800 years later than researchers originally estimated.

Hunt said that he chose to reevaluate previous radiocarbon results published for Easter Island due to inconsistencies in data reflecting the history of human settlement.

“It didn’t fit with what everyone believed about the island’s chronology,” said Hunt.

Hunt and co-author Carl Lipo of California State University, Long Beach, applied a “chronometric hygiene” approach to exclude samples—like old wood and shells from marine animals—known to cause inaccuracies in radiocarbon dating. They found evidence to support the current assumption that settlement of the island occurred around 1200 A.D., a date that compares favorably to dates applied to human impact on the environment of Easter island. Hunt says “the evidence for later settlement also fits well with the emerging picture of chronologies for Polynesia.”

A later settlement supports the premise that human impact on the environment played a key role in the downfall of Easter Island society.

“Human impacts to the environment, such as deforestation, began almost immediately, at least within a century,” said Hunt. “This means that there was no period where people lived in some ideal harmony with their environment; there was no early period of ecological sustainability. Instead, people arrived and their population grew rapidly, even as forest resources declined. The short chronology calls much of the traditional story into question.”

Last year Hunt presented research that argued that introduced Polynesian rats may have played a key part in the deforestation of the island’s 16 million palm trees which were key to sustaining Easter’s human population.

When Easter Island was first visited by Europeans in 1722, it was a barren landscape with no trees over ten feet in height. The small number of inhabitants, around 2000, lived in a state of civil disorder and were thin and emaciated. Virtually no animals besides rats inhabited the island and the local people—descended from a great line of seafarers, the Polynesians—lacked sea-worthy boats. Understandably, the Europeans were mystified by the presence of great stone statues, some as high as 33 feet (10 m) and weighing 82 tons (75 metric tons). Even more impressive were the abandoned statues-as tall as 65 feet and weighing as much as 270 tons. Anthropologists were long puzzled at how such a people could create and move such enormous structures with so little resources. The answer lay in Easter islands’ ecological past, when the island was not a barren place.

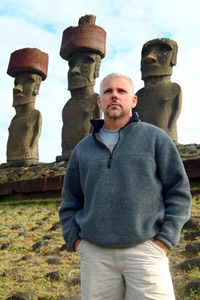

University of Hawaii at Manoa anthropology professor Terry Hunt. Photo by Jennifer Crites University of Hawaii at Manoa anthropology professor Terry Hunt. Photo by Jennifer Crites |

The Easter Island of ancient times supported a sub-tropical forest complete with the tall Easter Island Palm, a tree suitable for building homes, canoes, and latticing necessary for the construction of such statues. With the vegetation of the island, natives had fuel wood and the resources to make rope. With their sea-worthy canoes, Easter Islanders lived off a steady diet of porpoise. A complex social structure developed complete with a centralized government and religious priests.

It was this Easter Island society that built the famous statues and hauled them around the island using wooden platforms and rope constructed from the forest. The construction of these statues peaked from 1200 to 1500 AD, probably when the civilization was at its greatest level. However, pollen analysis shows that at this time the tree population of the island was rapidly declining as deforestation took its toll.

Around 1400 the Easter Island palm became extinct due to over harvesting and as Hunt argues, Polynesian rats, which severely reduced the palm’s capacity to reproduce by eating its seeds. In the years after the disappearance of the palm, ancient garbage piles reveal that porpoise bones declined sharply. The islanders, no longer with the palm wood needed for canoe building, could no longer make journeys out to sea. Consequently, the consumption of land birds, migratory birds, and mollusks increased. Soon land birds went extinct and migratory bird numbers were severely reduced, thus spelling an end for Easter Island’s forests. Already under intense pressure by the human population for firewood and building material, the forests lost their animal pollinators and seed dispersers with the disappearance of the birds. Today, only one of the original 22 species of seabird still nests on Easter Island.

With the loss of their forest, the quality of life for Islanders plummeted. Streams and drinking water supplies dried up. Crop yields declined as wind, rain, and sunlight eroded topsoil. Fires became a luxury since no wood could be found on the island, and grasses had to be used for fuel. No longer could rope by manufactured to move the stone statues and they were abandoned. The Easter Islanders began to starve, lacking their access to porpoise meat and having depleted the island of birds. As life worsened, the orderly society disappeared and chaos and disarray prevailed. Survivors formed bands and bitter fighting erupted. By the arrival of Europeans in 1722, there was almost no sign of the great civilization that once ruled the island other than the legacy of the strange statues. However, soon these too fell victim to the bands who desecrated the statues of rivals.

While tribal warfare likely reduced the population of Easter Islanders, Hunt suggests that most of the decline probably was resulted from early 18th-century Dutch traders, who brought diseases and took slaves from the island. Research elsewhere indicates that “first contact” diseases — like typhus, influenza and smallpox — carry extremely high mortality rates, often exceeding 90%. The first traders to reach the island likely carried such diseases which would have rapidly spread among the islanders and decimated the population.

Today Easter island is part of Chile and relies on tourism to sustain its small population. All that remains of the once great society is a few stone relics from the past.

This article used information from press materials from the University of Hawaii and previous mongabay.com articles.