794 species on brink of extinction find study

Rhett A. Butler, mongabay.com

December 12, 2005

Protecting 595 sites around the world would help address an imminent global extinction crisis, according to a study published today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Conducted by scientists working with the 52 member organizations of the Alliance for Zero Extinction (AZE), the study identifies 794 species threatened with imminent extinction by virtual of existing at only a single remaining site on Earth. The study found that just one-third of the sites are known to have legal protection, and most are surrounded by human population densities that are approximately three times the global average. Safeguarding these sites is key to saving these species from extinction say the authors of the study.

“Although saving sites and species is vitally important in itself, this is about much more,” said Mike Parr, Secretary of AZE, in a release from the organization. “At stake are the future genetic diversity of Earth’s ecosystems, the global ecotourism economy worth billions of dollars per year, and the incalculable benefit of clean water from hundreds of key watersheds. This is a one-shot deal for the human race,” he added. “We have a moral obligation to act. The science is in, and we are almost out of time.”

“We now know where the emergencies are: the species that will be tomorrow’s dodos unless we act quickly,” said Taylor Ricketts, lead author of the study. “The good news is we still have time to protect them.”

|

AZE is a joint initiative of 52 biodiversity conservation organizations, aims to prevent extinctions by identifying and safeguarding key sites, each one of

which is the last remaining refuge of one or more Endangered or Critically Endangered species, as defined by the World Conservation Union (IUCN). AZE’s goal is to identify sites in most urgent need of conservation and work to prevent species extinctions by eliminating threats to biodiversity and restoring habitat to allow wildlife populations to rebound.

The authors of the report say that while extinction is a natural process, the current human-caused rates of species loss are 100-1,000 times greater than natural rates. In recent human history, most species extinctions have occurred on isolated islands following the introduction of invasive predators such as rats, although the disappearance of large animals — the so-called megafauna of North America, Australia, Madagascar, and other parts of the world — is thought to also have resulted from human activity, notably hunting and landscape management with fire. The study shows that today the majority of at-risk sites and species are now found on continental mountains and in lowland areas.

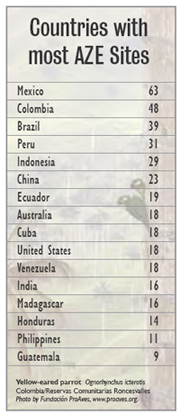

Mexico tops the list with 63 sites, followed by Colombia, Brazil and Peru. Latin America has more AZE sites then any other region on Earth due to its high biodiversity and rapid rates of habitat destruction. The United States is tied for eighth on the list.

|

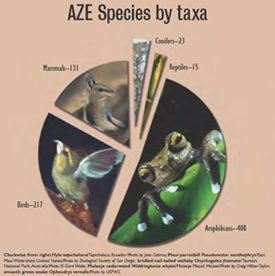

51 percent (408 species) of the listed species are amphibians, reflecting the dire position of a group of animals that includes frogs, toads, salamanders and caecilians. Since the late 1970s, amphibian populations have been rapidly declining and 129 species have gone extinct since 1980. Earlier this year, the Global Amphibian Assessment, a survey of the planet’s amphibian species, found that nearly a third (32%) of the world’s 5743 known amphibian species are threatened. While scientists don’t know what is ultimately behind this decline, the leading theory links global climate change to the emergence of deadly chytrid fungal disease. This fungus, which kills frogs by damaging the keratin layer of their skin, has decimated frogs worldwide.

Ecologists fear that the global decline of amphibians may have broader implications for the world’s environment. Because amphibians have highly permeable skin and spend a portion of their life in water and on land, they are sensitive to environmental change and can act as the proverbial “canary in a coal mine,” indicating the relative health of an ecosystem. As they die, scientists are left wondering what plant or animal group is next.

According to the AZE study, following amphibians are birds (217 species) and mammals (131 species).

This article used excerpts and quotes from press materials provided by the Alliance for Zero Extinction (AZE). For more information about the AZE, please visit zeroextinction.org.

Related articles

Toad on brink of extinction, scientists race to study amphibian for bioactive compounds

Under the bright florescent lights of the reptile house in the Bronx Zoo of New York, a colorful exotic toad makes its final stand. Once gathering by the thousands at the waterfalls of the Kihansi Gorge of Tanzania, the population of the Kihansi Spray Toad now stands at less than 200 individuals. The hasty construction of a desperately needed dam, built with good intentions by the World Bank, has relegated this species to the edge of existence. A decade ago the Kihansi Spray Toad thrived in its thoroughly unique habitat, the waterfalls of the Kihansi River, part of ecosystem that is one of only 25 Global Biodiversity Hotspots on the planet (Hotspots are regions noted for their extensive range of species in a very small area). The gorge is located in the Southern Udzungwa Mountains of South Central Tanzania, which possess the greatest biodiversity in all of Tanzania.

25 percent of the world’s 625 primate species at risk of extinction

Mankind’s closest living relatives—the world’s apes, monkeys, lemurs and other primates—face increasing peril from humans and some could soon disappear forever, according to a report released today by the Primate Specialist Group of IUCN-The World Conservation Union’s Species Survival Commission (SSC) and the International Primatological Society (IPS), in collaboration with Conservation International (CI).

Humans ate giant lemurs to extinction

Madagascar’s first inhabitants probably hunted the island’s largest animals to extinction according to research published in the November issue of the Journal of Human Evolution.

Food demand greater threat to wildlife than global warming

“Claims that global warming will destroy up to a million wildlife species — as recently featured on ABC’s Nightline — are willfully misleading,” warned Dennis Avery of Hudson Institute’s Center for Global Food Issues at the American Society of Animal Science’s annual meeting on July 24. Worse, said Avery, TV networks and wildlife biologists ignore the real threat to the world’s wildlife: a redoubling of human food demand over the next 50 years that could imperil vast tracts of wildlife habitat. Recognizing the food demand, however, would shift government research funds from climate models to politically incorrect agricultural research stations-our main hope to double crop and livestock yields.