Biopiracy fears hampering research in Brazilian Amazon

By Michael Astor, Associated Press

October 30, 2005

RIO DE JANEIRO, Brazil — Somewhere in the Amazon there may be flora and fauna that hold the key to curing diseases ranging from cancer to multiple sclerosis.

That, at any rate, is the dream. But the reality is that the search for the next miracle drugs is being hampered by a deep Brazilian suspicion of “biopiracy.”

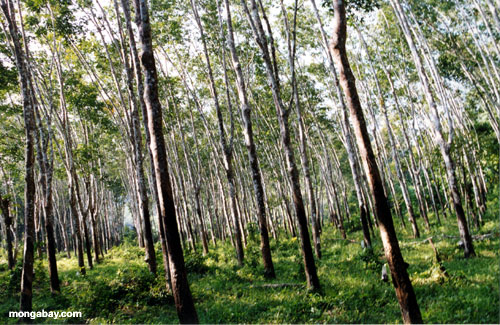

Rubber trees in southeast Asia. Brazil blames the British for illegally smuggling rubber seeds out of the Amazon rainforest in the late 19th century to establish plantations in Ceylon (Sri Lanka) and Malaysia. These plantations eventually cut Brazil’s share of the rubber market from a virtual monopoly to 20% in 1918. By 1940, Brazil’s share had fallen to 1.3% of the world rubber market. |

Some politicians, retired generals and Web sites seem convinced that the world’s biggest rain forest is crawling with biopirates scooping up seeds, leaves and animal blood samples whose genetic code might deliver the next miracle drug.

The government has imposed strict regulations which apply to both Brazilians and foreigners, but foreigners are more likely to get arrested. Over the past decade more than 30 have been detained, and their research samples confiscated or destroyed.

The Amazon rain forest is thought to contain at least 30 percent of all plant and animal species on the planet, most of them uncatalogued. At the same time, loggers and farmers are shrinking its area at a rate equivalent to six football fields a minute.

But scientists say the rules are so stringent and overzealously enforced that it has become impossible to ship samples abroad for analysis, reducing research to a crawl and driving many scientists to move their research to Ecuador, Bolivia and Peru.

Last year, police tracked two German researchers across eight Brazilian states and seized the spiders they were allegedly planning to ship to the United States.

In 2002, Marc Van Roosmalen, a Dutch scientist who has discovered some 20 new monkey species, was accused of biopiracy after authorities removed 27 rare monkeys from his home in the Amazon city of Manaus. Roosmalen says he was only studying and caring for the animals, not exploiting them for profit, and had applied for permits in 1996 and never heard back.

Brazilian scientists are feeling the squeeze too.

“The situation is so frustrating, I’ve all but given up,” says Paulo Buckup, a professor of ichthyology at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro who collects river fish for research. “Brazil has lost the capacity to control its own resources because it doesn’t know what it has.”

Biopiracy haunts Brazilian history, beginning with Henry Wickham, an Englishman who smuggled rubber seeds out of the country in the 19th century and broke Brazil’s global rubber monopoly.

Then came the 1992 Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro, which produced a convention entitling nations to a share of the profits from substances yielded by their flora and fauna.

“All the signers bought into a concept no one knows how to implement. Anyone can claim you’re not sharing the benefits, and the government is afraid of being held responsible,” said Dr. Roberto Cavalcanti, a zoology professor at the University of Brasilia.

Cavalcanti agrees regulation is necessary, but feels the best way to fight biopiracy is more investment and more Brazilians doing their own collecting. He also says the biopiracy concept “has been hijacked” by opponents of measures to protect the rain forest against commercial overexploitation.

A congressional committee is investigating biopiracy, and several prominent foreign scientists have been forced to prove they are not biopirates, including Thomas Lovejoy, the U.S. scientist credited with putting the plight of the rain forests on the world’s radar screen in the early 1980s.

He acknowledges he shares the blame for the biopiracy panic because of his own role in publicizing biodiversity.

“From my point of view, the real biopiracy is the destruction of the biodiversity of the Amazon,” said Lovejoy, president of the Heinz Center for Science Economics and the Environment.

Lovejoy was eventually cleared of vague charges that he was a CIA agent when he did research for the Smithsonian Institute in the Amazon years ago, and Congressman Jose Sarney Filho, a former environment minister on the biopiracy committee, acknowledges the investigation so far has little to show for its work.

“Up to now, we haven’t found a single concrete case of biopiracy,” Sarney told The Associated Press. “There are cases of spiders being contrabanded to American laboratories and things like that, but no material proof that our flora or fauna has been converted into medicine without following the legislation.”

But that doesn’t silence the cries of alarm.

Related articles Since very early on in human history, people have relied on medicinal plants to cure them of their various ills. Ethnobotany is the study of plant lore and agricultural customs of a people and is progressively being explored by pharmacologists for the development of drugs. Given their extensive range of knowledge of medicinal plants, indigenous people have traditionally been the ultimate resource for retrieving this information for purposes of application to modern medicine–the medicinal value of plants is very significant–no more so than today. Tropical rainforests are particularly endowed with plants possessing curative properties. These richly biodiverse environments provide a veritable trove of flora containing compounds of medicinal value, which indigenous people have utilized and benefited from for centuries. On April 13, 2005, the National Geographic Society and IBM announced the launch of the Genographic Project: Tracing Human Roots to a Single Origin, a controversial genetic research initiative that aims to reveal the intimate details of human migratory history. Data from the project will provide a map of world population patterns, originating from Africa and dating back 150,000 years. With funding from the Waitt Family Foundation, field scientists expect to gather close to 100,000 DNA samples from 11 isolated native populations on six continents. Rubber is one of the most important products to come out of the rainforest. Though indigenous rainforest dwellers of South America have been using rubber for generations, it was not until 1839 that rubber had its first practical application in the industrial world. In that year, Charles Goodyear accidentally dropped rubber and sulfur on a hot stovetop, causing it to char like leather yet remain plastic and elastic. Vulcanization, a refined version of this process, transformed the white sap from the bark of the Hevea tree into an essential product for the industrial age. |

“The internationalization of the Amazon goes far beyond the economic area and the occupations of lands,” Amazonas state Gov. Eduardo Braga warns. “They will take from us our flora and our fauna.”

Manaus Mayor Serafim Correa says Brazilians must “take care that we don’t allow our Amazon to be invaded.”

On the Web site “Amazon Love it or Leave It,” Gen. Luiz Gonzaga Schroeder Lessa, former chief of the Amazon Military Command, claims collectors disguised as religious or environmental groups are taking samples to be turned into medicines for which Brazilians will later have to pay them royalties. “It’s biopiracy and it goes on almost unchecked in the Amazon,” he writes.

Sarney, the congressman, says most Brazilians confuse biopiracy with things like a recent case where a Japanese company trademarked “Cupuacu,” a fruit unique to the Amazon. The trademark was revoked following protests from Brazil.

Rogerio Magalhaes, an environment ministry official, acknowledges the bureaucracy is frustrating, but denies it stops researchers from doing research.

“They’re doing it but they’re doing it illegally,” he says.

The legal limbo provides little comfort to scientists like Carlos Joly, director of the Botanical Institute at the University of Campinas in Sao Paulo state.

“Right now it seems like we — the ones who are doing research — are the pirates,” said Joly. “The best way to protect Brazil’s biodiversity is to know its characteristics and potential. That’s what the country should be investing in.”

ARTICLE CONTENT COPYRIGHT the Associated Press. THIS CONTENT IS INTENDED SOLELY FOR EDUCATIONAL PURPOSES.

mongabay.com users agree to the following as a condition for use of this material:

This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been authorized by the copyright owner. Such material is made available in an effort to advance understanding of environmental issues. This constitutes ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond ‘fair use’, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.

If you are the copyright owner and would like this content removed from mongabay.com, please contact me.