Fires in peat lands cost climate dearly

Tina Butler, mongabay.com

September 6, 2005

[An updated version of an April 2005 article]

The tropical rainforests of Kalimantan have long been threatened and increasingly endangered by deforestation and other invasive types of human activity. However, a lesser known ecosystem in the region that is literally coming under fire, is the tropical peat lands, particularly in the central area of the province of Indonesian Borneo.

Peat lands are a common and well-known feature of the natural environment northern latitudes such as Scotland, Ireland and Russia. In fact, close to 80 percent of all peat lands are found in the north. These organic deposits are comprised of partially decayed plant matter that accumulates over time. In Kalimantan, there is a distinctive tropical manifestation of this type of swamp, formed from the accretion of woody debris on the rainforest floor. Organic matter in the form of leaf litter, wood falls and other plant remains too wet to decompose collect in damp mounds that can be as deep as 66 feet (20 meters).

These tropical peat lands, formed over hundreds of years, are giant stores of carbon, which help maintain atmospheric balance of greenhouse gases. In addition, tropical peat lands serve as a natural means of flood control, acting like a sponge to absorb large amounts of rainfall and runoff, and reduce the threat of erosion.

Historically, typical peat bogs have absorbed carbon at much faster rates than their northern counterparts, but inappropriate land use and fires are transforming these carbon sinks into carbon sources. What is more, the remaining peat lands are losing their ability to serve as water buffers. After being logged, drained and burned to make room for agriculture, the peat lands have been left highly vulnerable to fire, leaving other areas at risk for subsequent flooding. While the peat lands absorb carbon, they also function to hold significant amounts of moisture. So as the peat lands are reduced in area, they are losing their water-retentive qualities. The dried-out peat lands in Kalimantan are now perfect fuel for fires.

In recent years, the circumstances compounding the instability of Indonesian Borneo’s peat lands have only intensified. In 1995, the country’s former dictator Suharto introduced the Mega Rice Project, which intended to turn Central Kalimantan into a “rice bowl” for Indonesia. The project called for the logging and draining of approximately 2.5 million acres (1 million hectares) of peat land for conversion into rice paddies.

|

Findings presented at the 2005 Annual International Conference of the Royal Geographical Society Dr Susan Page, Senior Lecturer in the Department of Geography at the University of Leicester, conducted a study on the burning of peatlands in southeast Asia and found that this ecosystem contains up to 21 percent of the world’s land-based carbon. While tropical peatlands — which are over 26,000 years old in the region — are spread across numerous islands in southeast Asia, including Borneo, Sumatra and Papua they are disappearing rapidly. An area the size of Belgium has been cleared and burned in just 8 years and at the current rate of burning, these peatlands could be destroyed before 2040, releasing a vast amount of carbon into the atmosphere. |

For two years, workers cleared the forests and dug almost 3000 miles of canals with the intended purpose of keeping the soil drained in the rainy season and crops irrigated in the dry season. But because the peat lands were higher than the rivers, the plan backfired as the canals carried all the moisture out of the peat lands. The failures of the project were compounded by an eight-month drought from an especially intense El Nino year. In 1997, the dried-out peat lands ignited. According to Dr Susan Page, Senior Lecturer in Geography at the University of

Leicester, 2.67 billion tons of carbon dioxide was released into the atmosphere from the fires, equivalent to 40 percent of one year’s total fossil fuel combustion and the largest release of carbon since records began in 1957.

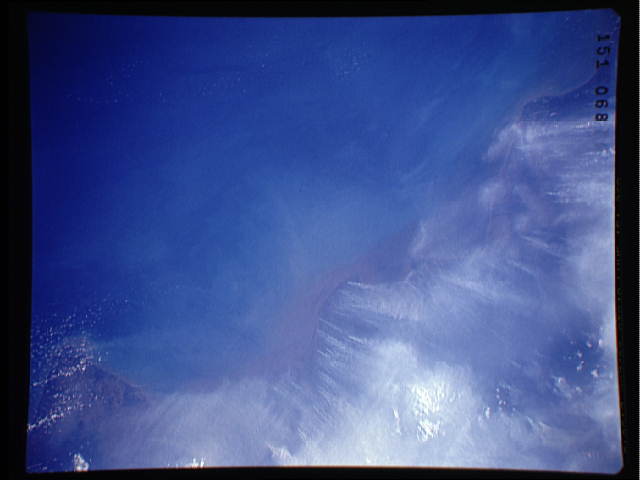

Most of the world’s peat lands are slight sinks or neutral in terms of carbon, but as the balance shifts due to human activity, this will change. Now that the peat lands regularly burn, these stores of carbon are becoming sources of carbon, rapidly increasing atmospheric concentrations of the gas. As the peat lands burn, thick, carbon-rich smoke and haze choke the atmosphere. Scientists are just now beginning to understand the role peat lands play in regulating greenhouse gases. The obvious potential long-term threat is global warming. The more immediate concern is the increased risk and incidence of significant flooding in low-lying coastal areas.

If global temperatures continue to rise, the peat lands will continue to dry out, making fires more likely, disrupting the natural balance and releasing even more climate-changing gas. Floods will be more common and more severe without the natural regulation provided by the swamps. Combined with the heavy deforestation in the same region and its associated problems, the future of Kalimantan appears to be in jeopardy.

More on Borneo:

A Brief Social History of Borneo

Tropical Hardwood Log Imports into Japan – Note Sabah & Sarawak which are provinces in the Malaysian part of Borneo

The Asian Forest Fires of 1997-1998