Lemur hunting persists in Madagascar, rare primates fall victim to hunger

Rhett Butler

July 17, 2005

Armand stares down at the trap made from sticks and ropes in the rainforest of Masoala. “For carnivores,” he says.

Armand examining a trap set for carnivores in the rainforest of the Masoala Peninsula

|

We have stumbled upon a series of traps within Masoala National Park, which holds one of the most biodiverse forests on Earth.

In these forests you’ll find about 50% of Madagascar’s species, despite their making up less than 2% of its land mass. Given the incredible biological richness the Indian Ocean island, finding these traps is particularly sobering. It reminds us that no matter how much land is protected in Madagascar the only way to preserve its rare and unusual species is to ensure that conservation provides immediate and ongoing benefits for local people.

Madagascar, a land of staggering biodiversity

A little larger than California, Madagascar is the world’s fourth largest island. Madagascar has been isolated from mainland Africa for about 160 million years and around 80% of its native flora and fauna are unique to the island. While Madagascar is best known for its lemurs it also is home to a number of other evolutionary peculiarities from the streaked tenrec, a spiny yellow and black insectivore that resembles a miniature hedgehog and makes grinding-chirping noises when threatened, to the fossa, a carnivorous mammal that looks like a cross between a puma and a dog but is closely related to the mongoose. Madagascar also has more than half the world’s chameleon species, neon green day geckos, three times as many kinds of palm trees as mainland Africa, and an entire ecosystem consisting only of endemic spiny plants. Needless to say, Madagascar’s flora and fauna make it one of the most biologically important places on Earth.

Lemurs are a key component in Madagascar’s biodiversity. Lemurs belong to a group of primates known as prosimians that were once distributed worldwide but today have been largely replaced by monkeys. It is only because of Madagascar’s isolation that lemurs have managed to survive and flourish. Currently about 60 kinds of lemurs are recognized by scientists, a number that has grown in recent years with the discovery of several new species including two this year. Despite these findings, Madagascar’s lemur diversity is considerably poorer than when humans first set foot on the island about 2000 years ago. Since then, the island’s largest lemurs species have been hunted to extinction and suffered from habitat loss induced by climate change and human activities (especially land-clearing with fire).

The disappearance of megafauna in Madagascar Until recently it was believed that Madagascar’s forests and extinct native species were primarily the victim of slash-and-agriculture by the island’s first human inhabitants. However, new research suggests other factors may have played a role in the mass extinction of Madagascar’s megafauna and decline of Madagascar’s native ecosystems, including:

As stated by paleoecologist David Burney in an October 2003 press item from Fordham University: “What you have here is a domino effect, an interaction of multiple causes culminating in the extinction of these animals … A problem that scientists have always had with the evidence was explaining how a small number of people with primitive hunting weapons could disrupt an ecosystem system so quickly. We found that it was most likely the interactive effects of human activities that account for the depth of these extinctions, which eventually eliminated the entire mega fauna on Madagascar.” |

Species under threat

Red ruffed lemur. |

|

These losses continue today as Madagascar’s species are increasingly under threat from habitat loss and poaching. While it has been illegal to kill or keep lemurs as pets since 1964, lemurs are hunted where they are not protected by local taboos (known as fady). Many lemurs are particularly easy targets for hunting because evolution has rendered them ecologically naive in that without natural predators over the majority of their existence, they are less fearful than they should be.

According to Masoala – The Eye of the Forest, a book published by the Zurich Zoo, in the rainforest of Masoala locals hunt with shotguns or use traps known as laly, described as “a cleared strip of forest 5m wide by 50m or more in length with snares set on one or two branches that are left for the lemurs to cross.”

Verreaux’s Sifaka (Propithecus verreauxi verreauxi) is famous for its “dance.” |

|

In the region around Isalo National Park, a sandstone massif in southeastern Madagascar, a commonly seen lemur called Verreaux’s sifaka is known as sifaka-bilany or “sifaka of the cooking pot” reflecting the culinary interests in this species among some Malagasy tribes and immigrants to the area. Even in areas were lemurs are protected by tradition, they may be poached by recent migrants from other parts of the island, who do not hold the same beliefs and taboos.

Dylan Lossie, a traveler from the Netherlands, and his guide Theo were recently shocked to discover a number of lemur traps in Ankarana Special Reserve, a protected area is known for its limestone karst pinnacles called tsingy along with its extensive cave system and network of underground rivers. Ankarana may have the highest density of primates of any forest in the world according to Bradt’s Madagascar Wildlife.

White-footed lepilemur (Lepilemur leucopus) |

|

“We found many lemur traps hidden in the forest,” reports Lossie. “These were built with long trunks forming a half circle and baited with food to capture lemurs. We also came across marking points placed under the lepilemur burrows so that they could be captured.”

Dylan and Theo destroyed all the traps they encountered.

“It’s apparent that ANGAP [Madagascar’s park service] is doing a poor job in Ankarana,” says Dylan. “For us to find several traps in such accessible parts of the park really reflects badly on the agency especially given their significant increase in park fees since my visit last year.”

The international pet trade plays a role

Other species too are subject to exploitation. Tenrecs and carnivores are also widely hunted as a source of protein, while reptiles and amphibians are enthusiastically collected for the international pet trade. Chameleons, geckos, snakes, and tortoises are the most targeted.

Local Malagasy simply putting food on the table

Malagasy children in Akavandra village. |

|

These problems stem from the fact that Madagascar is among the world’s poorest countries. As such, people’s day to day survival is dependent upon natural resource use. Most Malagasy never have an option to become a doctor, teacher, factory worker, or secretary; they must live off the land that surrounds them making use of whatever resources they can find. Their poverty costs the country and the world through the loss of the island’s endemic biodiversity.

ANGAP, the organization that manages Madagascar’s protected areas system, is generally in charge of patrolling parks, but this can be extraordinarily difficult given its budget constraints and basic needs of local people. While its staff is better trained that those in other parts of Africa, ANGAP alone can not rectify the competing interests of local people and conservationists.

ANGAP: working to bring conservation benefits to locals

One of ANGAP’s principal goals is to enable local communities to benefit directly from conservation. Thus 50% of park entrance fees collected by ANGAP go to local communities and visitors cannot enter a park without a hiring a local guide. ANGAP has extensive training programs to ensure local guides are knowledgeable about the flora, fauna, and other details of the protected area. ANGAP also works closely with domestic and foreign scientists to study biodiversity and the impact of visitors on parks and reserves.

Masoala, a place of beaches and rainforests |

|

Despite some recent criticism, ANGAP, with the help of organizations like the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) have worked to reduce poaching and improve conservation enforcement, especially on the Masoala Peninsula where they use aerial patrols to detect illegal land clearing and laly in and around the national park.

“With park boundaries extending over 526 km as the crow flies, dense forest, rugged terrain and few footpaths, it is almost impossible for park staff on foot to see tavy plots or the lemur traps known as laly unless they stumbled upon them by chance,” according to Masoala – The Eye of the Forest. “Aerial patrols, begun in 1998, have dramatically increased detection rates and also serve as an important deterrent for villagers who might otherwise be tempted to settle inside the park.”

ANGAP and WCS have also tried to provide communities with alternative sources of protein through fish-farming to help reduce the need to hunt wildlife.

Wildlife preservation is key to Madagascar’s economic growth

Through ecotourism, Madagascar’s wildlife may well provide the best hope for the country to emerge from its economic status as one of the world’s poorest countries where most earn less than a dollar a day and nearly half of the children under five years of age malnourished. Ensuring that wildlife preservation does not come at an unreasonable cost to local people is critical both to the success of conservation efforts and the growth of Madagascar’s economy.

Tourism in Madagascar Madagascar attracted 230,000 tourists in 2004, up from 160,000 the previous year, nearly two thirds of whom come from France, Madagascar’s former colonial ruler. The goal for the country’s nation tourist office is an annual 20 percent increase in the number of tourists, with a target figure of 684,000 in 2010. Madagascar has a lot of offer visitors but due to its remoteness, lack of infrastructure, and poverty it has largely failed to capitalize on its natural tourist attractions which include some of the best wildlife on the planet and fantastic landscapes. There is hope that Madagascar will be able to capitalize on the recent release of a Dreamworks’ film that shares the name of the island. Madagascar, the animated movie, has grossed more than $180 million in the seven weeks after its release in the United States. |

This article used information from mongabay.com, wildmadagascar.org, Masoala – The Eye of the Forest, local Malagasy guides, and Dylan Lossie.

Related articles:

- Madagascar hopes movie will boost tourism and economy

- Tourism in Madagascar; Visiting the World’s Most Unusual Island

- Why visit the real island of Madagascar?

- Seeking the world’s strangest primate on a tropical island paradise off Madagascar

- Madagascar looks toward a brighter economic future with movie, new aid package

- Down a river of blood into a remote canyon in Madagascar: Exploring the Manambolo River

- The Giant Jumping Rat, another peculiarity from Madagascar

- In Madagascar woodworking Zafimaniry remember lost forests

Save Madagascar T-shirt Sifaka lemur dancing shirt |

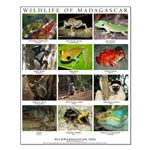

Madagascar Wildlife T-shirt Wildlife of Madagascar |

Save Madagascar T-shirt Wildlife of Madagascar |

Wildlife of Madagascar Poster in Malagasy and English |

FAQs:

Do people eat lemurs? Are people eating lemurs? Are lemurs hunted? Are lemurs poached? Do people poach lemurs? Are lemurs safe from humans? Are lemurs eaten by people?