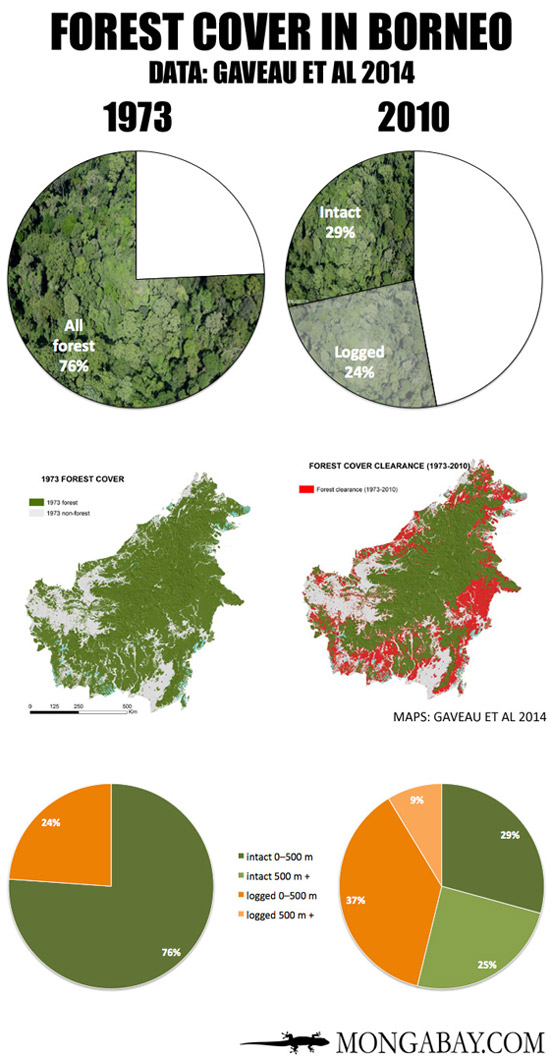

More than 30 percent of Borneo’s rainforests have been destroyed over the past forty years due to fires, industrial logging, and the spread of plantations, finds a new study that provides the most comprehensive analysis of the island’s forest cover to date. The research, published in the open-access journal PLOS ONE, shows that just over a quarter of Borneo’s lowland forests remain intact.

The study, which involved an international team of scientists led by David Gaveau and Erik Meijaard, is based on satellite data and aerial photographs. That approach enabled the researchers to separate industrial plantations from selectively-logged natural forests, while also mapping the extent of logging roads for various elevations, distinguishing between highly endangered lowland forests and inaccessible high-elevation forests.

The results are sobering for conservationists: intact lowland forests, which house the highest levels of biodiversity and store the largest amounts of carbon, declined by 73 percent during the period. 34 percent of those forests were selectively logged, while 39 percent were cleared completely, usually converted to industrial plantations to supply the world with palm oil, paper, and timber. Sabah, the eastern-most state in Malaysia, had the highest proportion of forest loss and degradation, with 52 percent of its lowland forests cleared and 29 percent logged. Only 18 percent of the state’s lowland forests remain intact, according to the study.

Chart showing forest loss in Borneo between 1973-2010.

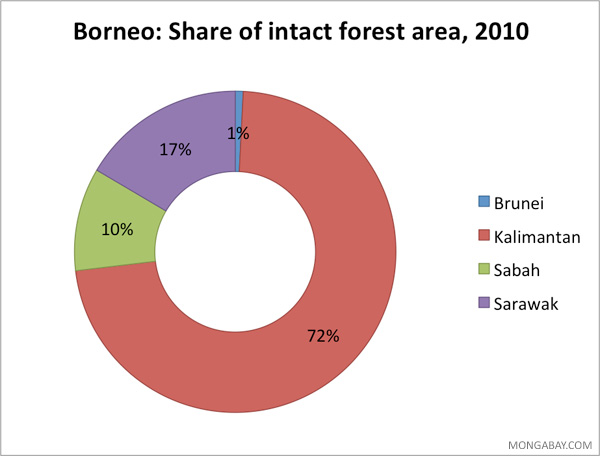

Forest loss was largest in Indonesian Borneo — the four provinces that make up Kalimantan — which accounts for more than 72 percent of Borneo’s land mass. Kalimantan lost an aggregate of 123,941 square kilometers over the period. It was trailed by Sabah (22,865 sq km), Sarawak (21,309), and Brunei (378 sq km). In percentage terms, Sabah lost 40 percent of its forests, Kalimantan 31 percent, Sarawak 23 percent, and Brunei 8 percent. Overall, Borneo’s forests are being destroyed at twice the rate of the rest of the world’s rainforests.

The research found that commodity production is an important driver of deforestation in Borneo. Forest degradation starts with logging roads, which grant access to remote areas for timber extraction. Once valuable wood has been harvested, forests may be bulldozed for industrial plantations. The study found that even inaccessible mountain forests are now being logged and converted for plantations.

“Forest conversion encompasses clearing forest to establish industrial oil palm (Elaeis guineensis), and to a lesser extent acacia (Acacia spp) and rubber tree (Hevea brasiliensis) plantations,” the authors write. “In 2010, the area planted in industrial oil-palm estates and timber plantations was 64,943 sq km and 10,537 sq km, respectively, representing 10% of Borneo.”

Four decades of forest persistence, clearance and logging on Borneo. Forest (dark green) and non-forest (white) in year 1973, and residual clouds (cyan) in Panel A. Areas of forest loss during 1973–2010 (red) in Panel B. Primary logging roads from 1973–2010 (yellow lines) in Panel C. Remaining intact forest (dark green), remaining logged forest (light green), and industrial oil palm and timber plantations (Black) in year 2010 in Panel D. Map and caption courtesy of the authors. Click to enlarge

The authors estimate that at least 271,819 kilometers of logging roads were opened between 1973 and 2010. That’s the equivalent of 58 trips between New York and San Francisco. Logging road density on the island is 16 times higher than in the Congo basin.

The heart of Borneo and the spatial progression of logging since 1973 depicting a logging ‘frontier’ moving steadily upward and inland, from the lowland coasts to the highlands. In many areas, logging roads are surrounding and abutting against the edges of highland protected forests – the last contiguous bastions of intact forest. Caption and map courtesy of the authors. Click to enlarge

While it’s easy to get lost in the numbers, the study confirms the heavy impact humanity is having on the rainforests of Borneo, which until 50 years ago were considered some of the wildest and most pristine on the planet, home to nomadic tribes and substantial populations of orangutans, pygmy elephants, and rhinos. Today those tribes’ traditions are all but gone, rhinos are on the brink of extinction, and orangutans and elephants are endangered. Meanwhile Borneo’s forests have transitioned from being a net carbon sink, absorbing greenhouse gases from the atmosphere, to a source, with deforestation and fires contributing to climate change.

Orangutan in Central Kalimantan, Indonesia. Borneo is home to some 50,000 orangutans, but the population is declining at an unsustainable rate due to habitat conversion for oil palm plantations and hunting.

But despite the dire situation, the authors haven’t lost hope. They suggest reclassifying timber concessions in natural forests as protected areas, while strengthening laws that require forests be left standing. Limiting conversion of native forests for oil palm plantations is a critical priority, as is developing and implementing valuation systems that account for the services healthy forests afford, including “the role forests play in sequestering atmospheric carbon and buffer water run-off and thus prevent soil erosion and flooding are important, as well as the more traditional potential economic value of timber and other forest products.”

That latter recommendation plays into emerging efforts in Indonesian Borneo to develop carbon conservation projects under the U.N. Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation (REDD+) mechanism. REDD+ aims to provide performance-based finance for protecting and better managing tropical forests, but the initiative has been slow to get off the ground due to concerns about adequate safeguards, complexities around implementation, and lack of political will to address climate change.

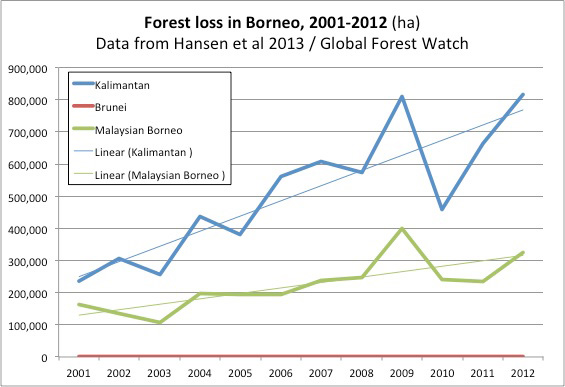

Beyond REDD+, a coalition of conservation groups have been pushing the Heart of Borneo initiative, which seeks to create new parks and link up existing protected areas across the central part of the island. But like REDD+, that endeavor has also stalled. Critics say the project doesn’t do enough to protect Borneo’s lowland rainforests, which the new study confirms are the island’s most endangered. And new data from Global Forest Watch suggests the situation may be getting worse.

Recent annual forest loss in Borneo, according to data from Matt Hansen and colleagues as presented on Global Forest Watch

Citation: Gaveau DLA, Sloan S, Molidena E, Yaen H, Sheil D, et al. (2014) Four Decades of Forest Persistence, Clearance and Logging on Borneo. PLoS ONE 9(7): e101654. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0101654

Related articles

Despite moratorium, Indonesia now has world’s highest deforestation rate

(06/29/2014) Despite a high-level pledge to combat deforestation and a nationwide moratorium on new logging and plantation concessions, deforestation has continued to rise in Indonesia, according to a new study published in Nature Climate Change. Annual forest loss in the southeast Asian nation is now the highest in the world, exceeding even Brazil.

Broken promises no more? Signs Sabah may finally uphold commitment on wildlife corridors

(06/23/2014) Five years ago an unlikely meeting was held in the Malaysian state of Sabah to discuss how to save wildlife amid worsening forest fragmentation. Although the meeting brought together longtime adversaries—conservationists and the palm oil industry—it appeared at the time to build new relationships and even point toward a way forward for Sabah’s embattled forests.

80% of rainforests in Malaysian Borneo logged

(07/17/2013) 80 percent of the rainforests in Malaysian Borneo have been heavily impacted by logging, finds a comprehensive study that offers the first assessment of the spread of industrial logging and logging roads across areas that were considered some of Earth’s wildest lands less than 30 years ago. The research, conducted by a team of scientists from the University of Tasmania, University of Papua New Guinea, and the Carnegie Institution for Science, is based on analysis of satellite data using Carnegie Landsat Analysis System-lite (CLASlite), a freely available platform for measuring deforestation and forest degradation. It estimated the state of the region’s forests as of 2009.

Industrial logging leaves a poor legacy in Borneo’s rainforests

(07/17/2012) For most people “Borneo” conjures up an image of a wild and distant land of rainforests, exotic beasts, and nomadic tribes. But that place increasingly exists only in one’s imagination, for the forests of world’s third largest island have been rapidly and relentlessly logged, burned, and bulldozed in recent decades, leaving only a sliver of its once magnificent forests intact. Flying over Sabah, a Malaysian state that covers about 10 percent of Borneo, the damage is clear. Oil palm plantations have metastasized across the landscape. Where forest remains, it is usually degraded. Rivers flow brown with mud.

Charts: deforestation in Indonesia and Malaysia, 2000-2010

(07/15/2012) Indonesia and Malaysia lost more than 11 million hectares (42,470 square miles) of forest between 2000 and 2010, according to a study published last year in the journal Global Change Biology. The area is roughly the size of Denmark or the state of Virginia. The bulk of forest loss occurred in lowland forests, which declined by 7.8 million hectares or 11 percent on 2000 cover. Peat swamp forests lost the highest percentage of cover, declining 19.7 percent. Lowland forests have historically been first targeted by loggers before being converted for agriculture. Peatlands are increasingly converted for industrial oil palm estates and pulp and paper plantations.